To Logan Pearsall Smith

To Logan Pearsall Smith

C/o Brown Shipley & Co

123 Pall Mall, S.W.1.

Paris. June 9, 1921

Thank you very much for taking such a constant and fruitful interest in my productions, now that your special godchild, Little Essays, has been definitely presented and made its bow in polite society. The article in the London Mercury is very nice and friendly all round, and I am delighted and surprised to see how thoroughly Arthur McDowall understands me. I am used, from my American critics, to a sort of vague estrangement and beating round the bush; here all is simple and direct, and I am quite aware that it is my fault if the technical side of my philosophy is not treated very seriously. I haven’t treated it very seriously myself, as yet, but I assure you there is solidity in it, if its skeleton were properly laid bare, as I hope before long to do, as a counter-poise to my excursions into the realm of fancy.

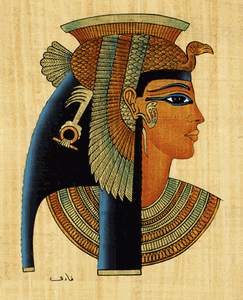

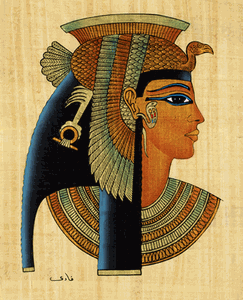

Taking your hint, I sent yesterday a Soliloquy—a very pagan and sentimental one on Hermes—to the editor of the London Mercury. Others are appearing in New York in the Dial—a sophomoric paper which I don’t mind, because its foolishness is youthful foolishness. But I can’t stand the perversity of the Nation-and-Athenaeum. What mad ghosts these liberals are! I am not surprised—to make a transition which isn’t one—that both the Russells are in love, but my wonder is that they can still pursue matrimony, and that they find anybody, I don’t say to love them, for I quite understand their perennial charm, like that of Cleopatra, but to trust or to wed them. When will the public, and the individual, realize, as you and I seem to have done, that in this absurdly over-populated world, there ought to be a large class of celibates to do the thinking? And it is far better for the intelligence of the future age that we should not leave children in the flesh—they would all be stark mad and most unhappy—but should only rationalize the atmosphere in which the sturdy average mortal, the child of the merely child-bearing woman, should be brought up. Mankind is faced with two awful dangers, between which we naturalistic monks may be able to steer them—the danger of losing their traditions and the danger of keeping them.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Three, 1921-1927. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

Location of manuscript: Library of Congress, Washington DC