To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

Paris. July 10, 1930

From your two letters I gather that, while you wish to put a good face on it, you are not really very happy at the Frascati, and may not be able to stand it long. I am sorry, but know only too well the difficulty that the homeless have in finding a home. It doesn’t seem worth while for me to go to Havre; life there would be very confined; here there is all the freedom and stimulus of Paris, and in spite of the terrific noise at the Foyot I have been able to sleep well and to do some writing both in the morningand the afternoon. However, I am moving tomorrow to a nice large paneled room, with a bath, at the Hôtel Vouillemont, rue Boissy d’Anglas: although not exactly quiet it will be less thundering and at least I shall avoid the nerve-racking journeys to and fro in autobusses and underground trains. There will be no need of my staying there forever; and if you discover some genuine paradise, I shall be ready to join you almost at any time.

As to your fresh statement of your position, it doesn’t help me much. I see how the sense of something going on in me, when I have that sense, should lead me to posit something outside (this is “projection” if I understand it): it might happen if I was addressed in action or watchfulness to the outside, and had only that private feeling within me to distinguish that object by. Images internally bred may thus “be used” to describe objects of intent in the environment, or in parts of my own body. But I remain incapable of conceiving how a substantial state can be projected.

As to introspection, I follow your analysis easily until you come to “rightly in respect to its nature, feeling”. What is rightly known in introspection, as in perception, is that there is something at the point focused responsible for what I feel and justifying my reaction. It does not enhance the truth of this discovery to add that, at that point, there is something abstractly similar to my present feeling. The pertinent and sufficient similarity in the known object to the knowing organ is that both should exist dynamically, so as to be able to affect and modify one another. I see that this existence would have to be “feeling., if we accept the idealistic dogma that nothing save “feeling”—meaning conscious feeling—can exist: but for a realist, who believes in the reality of objects posited in action, that argument falls to the ground and only epistemological considerations are pertinent.

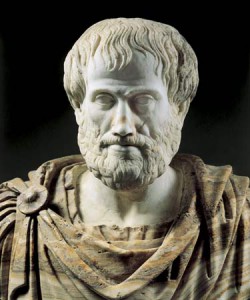

Since your previous exposition I have an inkling of a deep-lying cause of misunderstanding between us. “Luminosity” to me (and Aristotle) is proper to spirit, not to substance: the notion that a sort of diffused luminosity or potential spirit, should be the substance of the universe is strange to me. Is it a sort of psychological version of pure potentiality or materia prima? If so, I see a difficulty, in that mere potentiality (see Maritain) is necessarily resident in something else, which is actual. But what would be the actually formed being which contained the potentiality of eventual intuitions? Unformed intuitions, feeling without character, would never do: perhaps you would say space and instants—but that is another difficulty.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Four, 1928–1932. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY