To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

C/o Brown Shipley & Co

123 Pall Mall, London

Box Hill, Surrey. July 20, 1905

In my fifth volume, which I am now revising, I have added a note about your philosophy (not mentioning you). Lest there be any misrepresentation I copy it here and beg you to point out anything that is wrong. Of course you must not ask me to leave out the joke; but apart from that I will change anything. The text has been saying that the philosophy of mind is in hopeless confusion since “it is not settled whether mind means the form of matter, as with the Platonists, or the effect of it, as with the materialists, or the seat and false knowledge of it, as with the transcendentalists, or perhaps after all, as with the pan-psychists, means exactly matter itself.” Here follows the note: “The monads of Leibniz could justly be called minds, because they had a dramatic destiny and the most complex experience imaginable was the state of but one monad, not an aggregate view or effect of a multitude in fusion. But the recent improvements on that system take the latter turn. Mind-stuff or the material of mind is supposed to be contained in large quantities within any known feeling. Mind-stuff, we are given to understand, is diffused in a medium corresponding to apparent space (what else would a real space be?), it forms quantitative aggregates, its transformations or aggregations are mechanically governed, it endures when personal consciousness perishes, it is the substance of bodies, and, when duly organised, the potentiality of thought. One might go far for a better description of matter. That any material must be material might have been taken for an axiom; but our idealists, in their eagerness to show that “Gefühl ist Alles”, have thought to do honour to the spirit by forgetting that it is an expression and wishing to make it a stuff.

There is a further circumstance showing that mind-stuff is but a bashful name for matter. Mind-stuff, like matter, can be only an element in any actual being. To make a thing or a thought out of mind-stuff you have to rely on the system into which that material has fallen. The substantial ingredients, from which an actual being borrows its intensive quality, do not contain its individuating form. This form depends on ideal relations subsisting between the ingredients, relations which are not feelings but can be rendered only by propositions.”

To this note is reduced the chapter I had written about “Natural philosophy in quest of substance”: for I find that to keep volume five within limits I must reject everything not strictly falling under its title “Reason in Science”. A chapter on “Transcendentalism” which I love like the apple of my eye is also sacrificed: so that when I have had a good rest and am back in Cambridge I may begin to rival you other prolific article-writers out of the slaughtered innocents born to bloom in the L. of R.

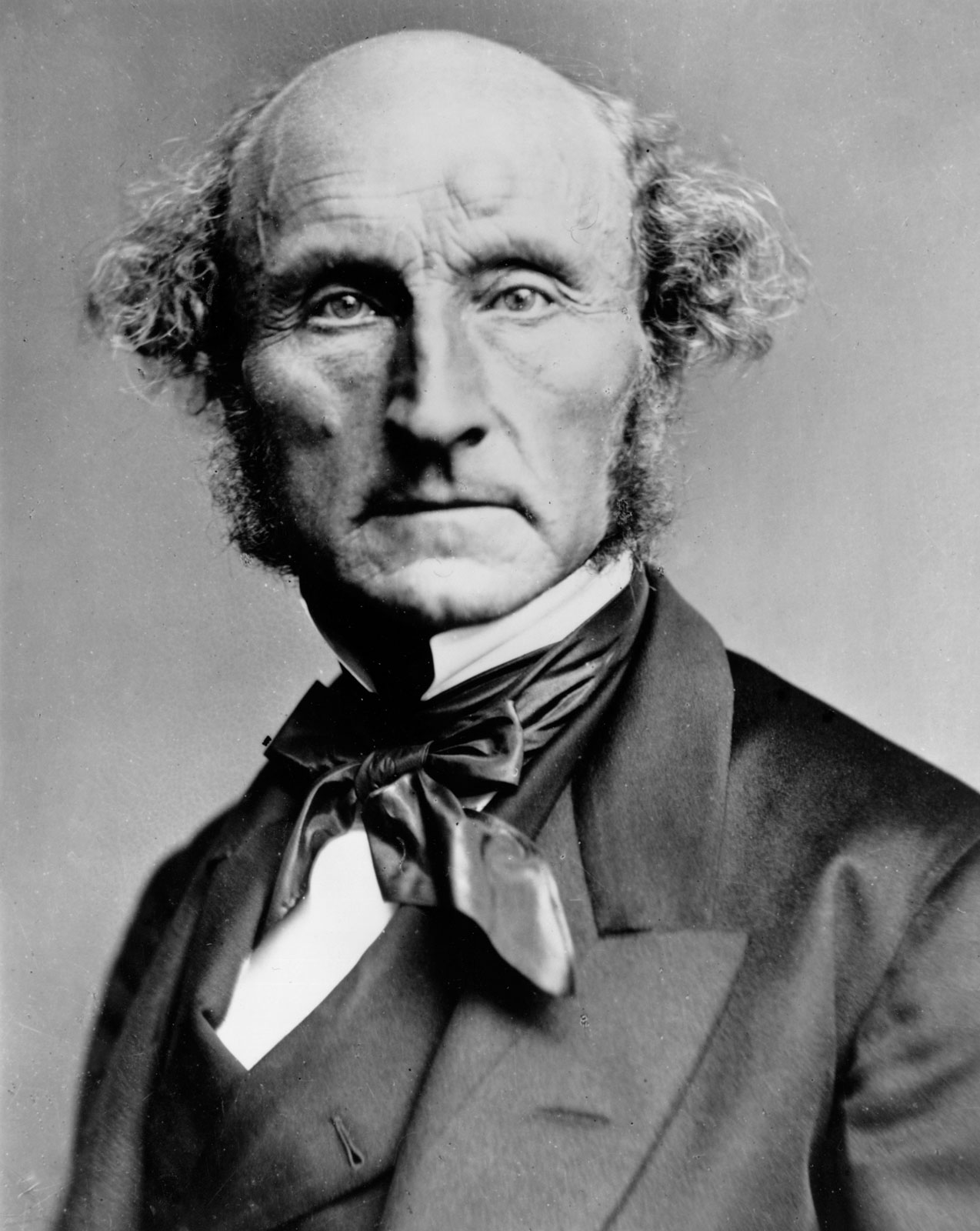

I have found a (somewhat vulgar) retreat here among the hills between Surrey and Sussex, and am making rapid progress with my work. As a relaxation I am reading Mill’s Logic.3 What bad logic—but what good feeling and good scholarship and pure wisdom! He is a sort of steadier and four-footed James.

President Eliot writes me that they have collected $2,400,000 for increasing our Harvard salaries. It sounds magnificent, but I believe it doesn’t amount to $500 a piece. Yours ever G.S.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY