To William Morton Fullerton

To William Morton Fullerton

Avila, Spain August 31, 1887.

Dear Fullerton—

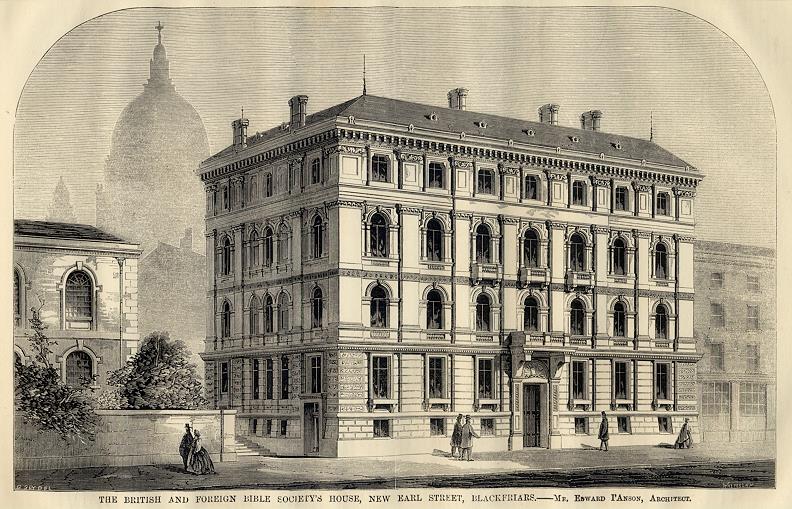

Thanks very much for your interesting letter, which I read in bed this morning, being at present convalescent from a little bilious attack that has recently turned me inside out. This biliousness of mine will give you optimist a chance to attribute any disagreeable and unsightly truth I may hereafter mention to the stock cause, viz, to indigestion. Men having generally turned their eyes to more profitable uses than seeing, when ever they discover anything it is supposed to be by means of that larger organ called the liver. Were we bilious people not here in rather large numbers, to enlighten the world, to what depths of superstition and infatuation would not you comfortable hypocrites have brought it! I confess I am overwhelmed by the catalogue of your collection honors and glories. I tremble in addressing such a high and famous authority. I marvel at his having deigned to write me a sixteen-page letter. I am going to have it framed in four nickle frames (until the times turn golden) between two plates of glass, so that both sides may be legible. These four tablets I shall hand down to my nephews (for like the Pope I shall have only nephews) as the main part of their inheritance (indeed, they won’t get much else.) Meantime I shall treasure them in an ark, modelled on the ark of the covenant, and for this purpose I write by this mail to the British and Foreign Bible Society for a Bible, in order to inform myself on the subject of ark-architecture. Alas! my own Bible, that my mother gave me with tears in her eyes, begging me never to part with it, has disappeared in the most tragic and lamentable manner. Being often in Popish and other heathen countries, I naturally carried my Bible jealously in my breeches pocket, lest the Inquisition or some tribe of cannibals should confiscate it and desecrate it, incidentally wasting and eating me as a Christian and a brother. But sad and strange experience has convinced me that the reason why in these godless countries there are no Bibles is not because the Devil, therein supreme, prohibits them, lest men should believe and be saved. The reason why Bibles are not found is because there is an alarming scarcity of paper, none being to be found even in water-closets. Now, as I am unfortunately a great frequenter of these establishments, on account of biliousness, diarrhoea, indigestion, dyspepsia, and colic; and as at the same time, mindful of my dear and sainted mother’s last wishes, I always carry my Bible in my breeches’ pocket; I have found myself in a cruel dilemma. Godliness said “Treasure thy Bible, and on no account tear out the leaves thereof.” But cleanliness answered “Did not David eat the consecrated bread when he was ahungered, and did not the Lord justify David? Tear thou then out likewise the leaves of thy Bible, and wipe thine ass therewith for thy need is as pressing as David’s, nay more.” And when I considered that since I was in England I have given up the use of drawers, and that the British and Foreign Bible Society might not be willing to send me a clean pair of trousers, even if I told them in what sacred cause I had sacrificed those I possessed,—when I considered those things I always decided in favor of cleanliness. I was careful, however,—I must say this in my own justification,—to begin by tearing out the Song of Solomon, and the passage about Loch’s daughters, and Ecclesiastes, and the pages descriptive of Sodom and Gomorrah, and such others as I thought godliness wouldn’t much care about. Still, as time went on, and my visits to water closets unprovided with paper continued, more and more of my Bible has disappeared, and now, I regret to say, only the upper half of the first page of the Gospel according to St. John remains. That is why I have to send to the British and Foreign Bible Society for a new copy in which to learn how the ark was built. When it comes, I assure you your letter shall be worthily enshrined.

Of course, when you are planning a novel, you must have had some experience of the tender passion. If you are engaged, or expect to be so, of course I cannot ask for any confidences, but if your loves have been less serious, or if unfortunately they have been unhappy, why don’t you tell me something about them? You know I am very prudent and sympathetic (I think I can say that without arrogance) and although I haven’t the genius, etc. of your new friends, I can FEEL! Besides as I have always been an admirer of yours, and not of your intellect alone, I have some right to be treated with confidence. I therefore think you might tell me something, when you next find time to write to me, about the inner side of all this full life of yours. All these great friends of yours have daughters, and all of these daughters have eyes, and some of them, at least, hearts. Ergo, when a handsome and fascinating young man, with the most brilliant prospects, appears upon the scene as if by magic, and carries everything before him, it is not credible that these maidens should all prove insensible. Something must have happened.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.