To Susan Sturgis de Sastre

To Susan Sturgis de Sastre

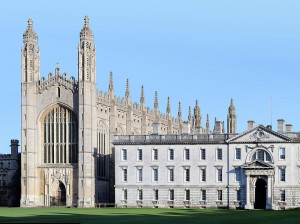

King’s College

Cambridge, England. January 14, 1897

My life here is as quiet as possible without any excitements or notable variations. The people are much to my mind, being refined, simple, and serious, but theirs is a slow fire and it takes a long time to get warm at it. Sometimes it seems as if the time for going away would come before I had really got into the ways of the place. I have made several valuable acquaintances, especially that of a man named Dickinson, a tutor at King’s, who is the type of everything I like and respect in the way of intelligence and feeling. I walk with him sometimes, and also with other young men, and we ask one another to lunch and breakfast, as is the custom in these parts. Dinner, as you know, is in Hall, and we go afterwards to a smoking room, where the papers are, to have coffee and perhaps a game of whist or chess; not that I play myself, as I prefer to do nothing when there is nothing to. Perhaps what I shall carry away from this prolonged visit to England more than anything else will be a love for the fields and the country air: it was one of the dreadful lacks in our education that we had nothing of that, and I feel it now as a permanent incapacity and disadvantage; the last six weeks of Paris and London have made me feel the change, for already I miss the country, and feel the oppression of pavements and walls, and the need of space and silence. Oxford last summer was a paradise in that respect, and I shall never forget my long solitary walks about that lovely region. The river here in the boating season is also beautiful, with its willows and broad fields, and the crowds of students, in their bright blazers, and in every sort of athletic costume, moving about on the water and the banks. It is a very simple, youthful life every one leads here, and Harvard in comparison seems constrained and corrupt. It is also more interesting, I must confess, and this Cambridge to say the truth is very dull. I should have stayed at Oxford if it had been possible to enter any college there except as an undergraduate (which I could not become again with dignity at this late day.) Here they are beginning to admit graduates to advanced standing (I eat and live with the Dons, and am not subject to ordinary regulations) and therefore I had to come here or remain at Oxford unattached to the University, which would not have served my purpose. However, you mustn’t think I am not satisfied with my experiment. I am: only more exciting and interesting surroundings could be imagined than these.

I came back to London to do a very singular thing—to give evidence in a cause célèbre. My unfortunate friend Russell has been pursued by his wife with two great lawsuits already, which she has lost, of course, as well as her reputation. But exasperated by this, Lady Scott, the mother-in-law, got up a most abominable libel on her daughter’s husband, had it printed in a disreputable hole, and circulated it anonymously in all the clubs and other places where Russell could have friends. He had no choice but to have her arrested, as well as her accomplices, and as the publication of the libel was proved against them beyond doubt, they took the impudent course of asserting that all it contained was true. Then it became necessary to disprove the various stories the libel contained, and as one of them was put at a time—June 1887,—when I was with Russell at Winchester, my evidence as to what there occurred became useful. There were many complications in the case—as the death of one of the prisoners—and at last, after all had been done that was possible to ruin Russell’s reputation—Lady Scott and her people threw up their case, and pleaded guilty. They were sentenced to eight months imprisonment, a year being the maximum the law allows in such a case. The matter thus ends, but it has been a most scandalous and disgusting affair, and even with the certainty of ultimate success, Russell and his friends have had to go through dreadful moments. It is not pleasant to hear one of one’s best friends accused in public with the utmost art and deliberation, of all that is most shocking and dishonourable, and not to know how many people all over the world will hear only that accusation—never the disproof of it—and believe it. But the judge did his best to put things right in the end, and to vindicate Russell, who has shown a most admirable courage and patience through it all. But I shouldn’t wonder if when Lady Scott comes out of prison she didn’t do something even more desperate. His house was burned to the ground, not long ago, and there was for a moment some fear it might have been done at her instigation. That however seems not to have been the case, but anything of the sort, even an attempt on Russell’s life, would not be surprising from such wicked and vindictive women. I never heard of such characters in life or in fiction.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Alderman Library, University of Virginia at Charlottesville.