To George Sturgis

To George Sturgis

Hotel Savoia

Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. July 15, 1937

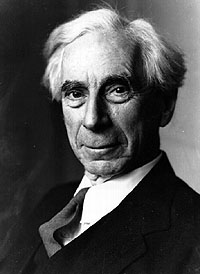

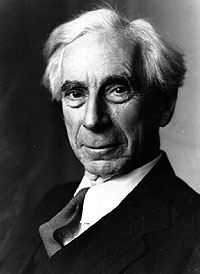

If I were superstitious, I might now attribute to divine interposition my odd reluctance to sign that will prepared last year. Here, quite unexpectedly, an occasion presents itself to use the $25,000 coming from the novel for purposes of the same friendly or public-spirited sort as those of my proposed will, but far more concrete and pressing. Let us annul the legacies to Mercedes, Mrs. Toy, Onderdonk, and Cory, as well as the added gift of $10,000 to Harvard for my Fellowship fund. A perfectly ideal incumbent for that Fellowship appears in Bertie Russell, old and almost penniless, but still brimming with undimmed genius and suppressed immortal works!

You know, I suppose, who Bertie is: a leading mathematician, philosopher, militant pacifist, wit, and martyr, but unfortunately addicted to marrying and divorcing not wisely but too often. He is now Earl Russell—that is his legal name—being brother and heir to my late life-long friend (the original, in part, of Lord Jim in my novel). They are grandsons of Lord John Russell, the reforming prime minister, and both ultra-radical in religion and politics. . . . Bertie for a long period was Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, where I used to see him almost daily in 1896-7; but he had to resign during the war, having been put in prison for pacifist agitation, as his brother had been put in prison for bigamy. Jail-birds! but only out of pure aristocratic freedom of thought and conduct.

I don’t agree with him in politics or in philosophy, yet we are good intellectual friends; our minds are too different, also our fields, for much friction, and we can enjoy each other’s performances without envy. Now, as to what I should like to do. It is to send Bertie £1,000 or $5000 a year for three or four years, but anonymously. This anonymity is important, because he and his friends think of me as a sort of person in the margin, impecunious, and egoistic; and it would humiliate Bertie to think that I was supporting him. And all [his] bevy of relations—especially the Smiths who are great gossips—would exaggerate and misinterpret everything in a disgusting way.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Six, 1937-1940. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA