To Martin Birnbaum

To Martin Birnbaum

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. February 4, 1946

Dear Mr. Birnbaum,

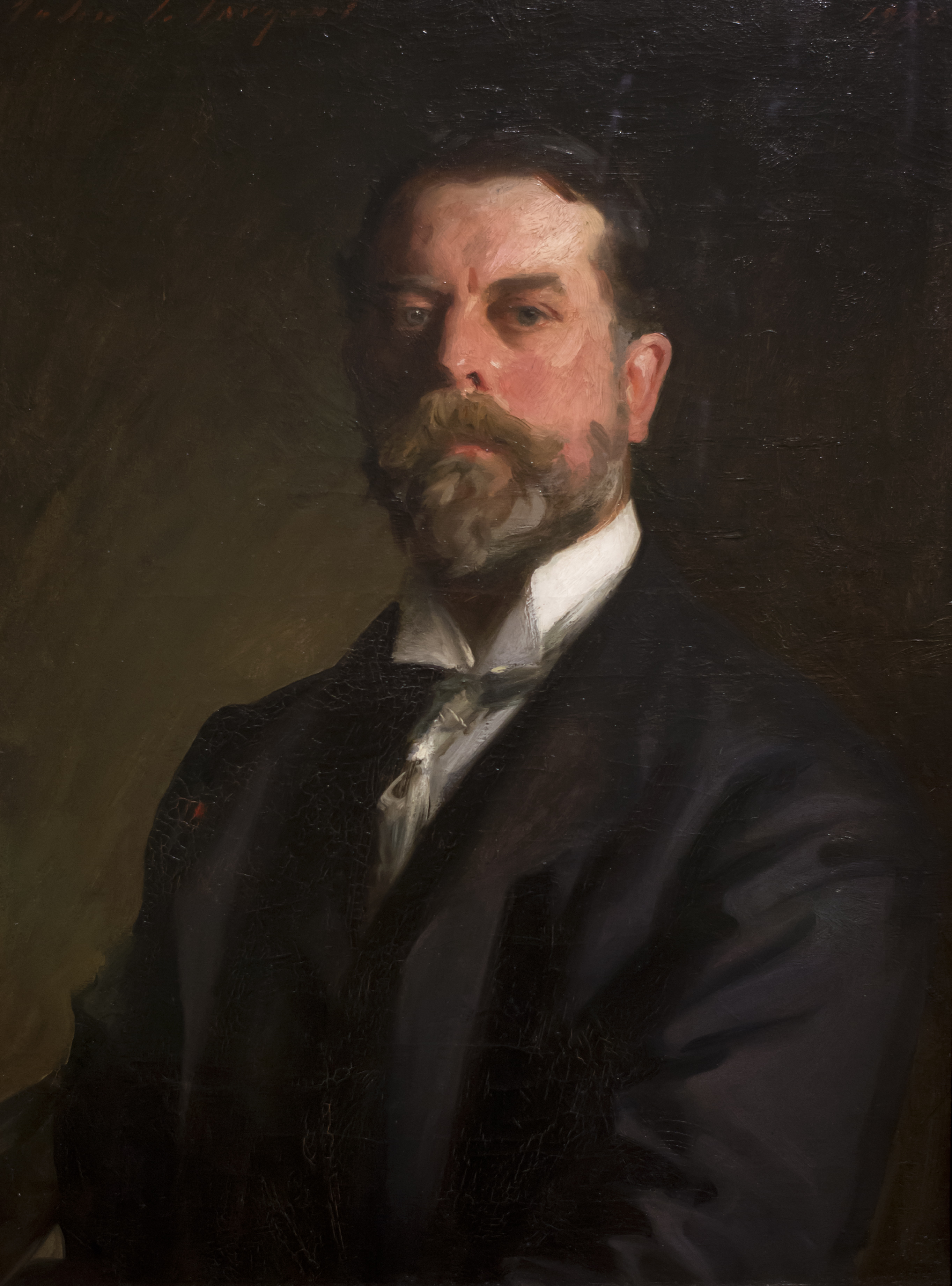

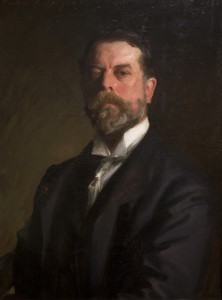

I write to thank you very much for your reminiscences of Sargent, including those of Henry James and the plates of some of Sargent’s paintings and drawings. I wish that you had gone more systematically into the problem of naturalistic versus eccentric or symbolic painting. It is a subject about which my own mind is undecided. My sympathies are initially with classic tradition, and in that sense with Sargent’s school; yet for that very reason I fear to be unjust to the eccentric and abstract inspiration of persons perhaps better inspired. Two things you say surprise me a little: one that Sargent was enormous physically. I remember him as a little stout, but not tall: and I once made a voyage by chance in his company, and thereafter a trip to Tangier; so that I had for a fortnight at least constant occasions to go about with him; and being myself of very moderate stature I never felt that he was big. The other point is that he saw and painted “objectively”, realistically, and not psychologically. Now, certainly he renders his model faithfully; but in the process, which must be selective and proper to the artist, I had always thought that, perhaps unawares he betrayed analytical and satirical powers of a high order, so that his portraits were strongly comic, not to say moral caricatures. But in thinking of what you say, and quote from him, on this subject, I begin to believe that I was wrong, that he may have been universally sympathetic and cordial, in the characteristically American manner, and that the satire that there might seem to be in his work was that of literal truth only: because we are all, au fond, caricatures of ourselves, and a good eye will see through our conventional disguises and labels. And this would explain what to some persons seems the “materialism” of Sargent’s renderings; his interest in objets d’art for instance, rather than in the vegetable kingdom or in the life of non-sensuous reality at large. Crowding his house with pictures, and his memory with innumerable friends and innumerable anecdotes about them, shows a respect for the commonplace, a love of the world, that prevents the imagination from taking high flights or reflecting ultimate emotions.

Is there, I wonder, any truth in such a suspicion?

Yours sincerely,

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Seven, 1941-1947. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006.

Location of manuscript: Unknown