To Horace Meyer Kallen

C/o Brown Shipley & Co.

123 Pall Mall, London

Cambridge, England. November 10, 1913

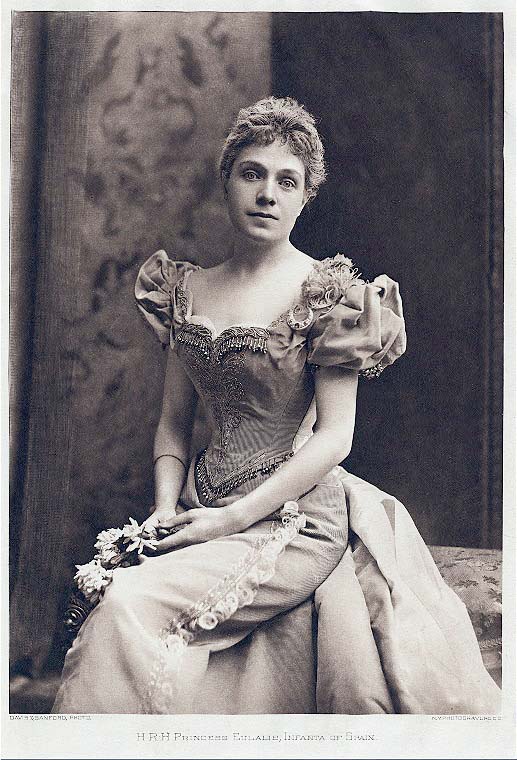

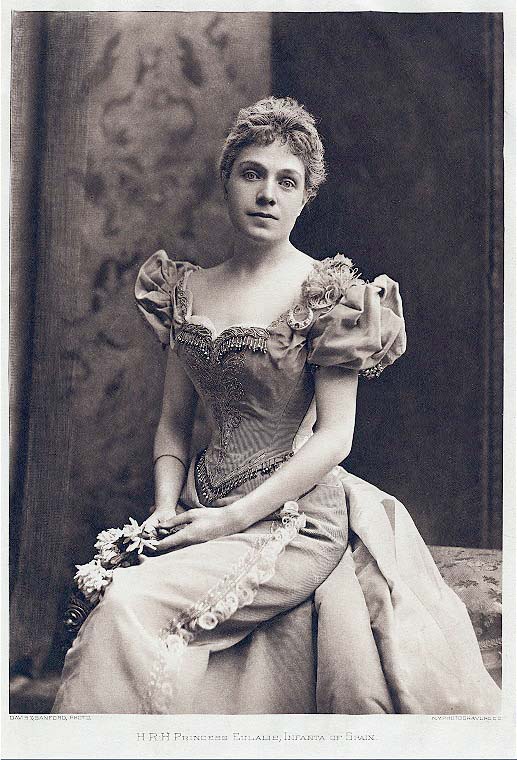

I should sympathize heartily with such revolutionary yearnings if it was only a question of destroying the snug and limping conventions under which we live. But I dread what might be substituted for them. One of the fatalities of my life has always been that the people with whom I agree frighten me, and I frighten those with whom I naturally sympathize. No: that isn’t it exactly, because I don’t sympathize with the old fogueys as they now are, nor with any stale convention; but I love the sentiment and impulse out of which these now stale conventions once arose, far better than the impulse and sentiment out of which springs the rebellion against them. Life, yes, but not this life. My eye has just fallen, by chance, on an article by the Infanta Eulalia of Spain about her childhood. It is full of hatred of Spain of Catholicism and of virtue, and slips into positive lies: it is a horrible expression of impiety, in every sense of that word. Well, the things the Infanta hates are, I agree, tyrannical conventions, and a straight-jacket for sanity—not to speak of the eroticism from which the lady evidently suffers. But imagine the treble horror of the tyrannical conventions which an inhuman impiety and low-mindedness, such as hers and that of her free-thinking circle is, would impose on mankind! I should rather have the Inquisition back again. I have also just finished a book, interesting to one of my generation, on the “Eighteen Nineties” by one Holbrook Jackson. It brings to a focus the rebellious, conceited, pessimistic aestheticism that was fashionable in my youth; I can see now that I was not unaffected by it, although the elements which these aesthetes added when, at the end, they were converted (most of them died Catholics) was always present in my background, and besides I was not clever enough to be nothing else. It is very interesting to compare with that spirit of the Eighteen Nineties that of the ‘Teens of the new century. It is a very different spirit—the Infanta Eulalia, thank Heaven, is an old woman now—and in Paris especially one feels it in every wind. It is unintellectual, virtuous, athletic, patriotic, cooperative; it accepts conventions with respect but without illusion, and it takes pains to find means to its ends, without giving to these ends a universal or exaggerated value. I like it. It is the spirit of an honest, modest, vigourous young artisan.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Two, 1910-1920. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: American Jewish Archives, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati OH