To Charles G. Spiegler

To Charles G. Spiegler

C/o Brown Shipley & Co.

123, Pall Mall, London. S.W.1

Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. September 2, 1939

Dear Mr. Spiegler,

The sonnet about which you say “there has been rather heated discussion” was written fifty-five years ago, and I should hardly trust myself to say now exactly what interpretation, if any, might exactly correspond to what may have been in my mind when I wrote it. I say, if any, because at twenty the mind is susceptible to momentary lights, and my sonnet wasn’t written at one sitting. When I came to “the soul’s invincible surmise” I was probably thinking simply of Columbus; but when I came to “the light of faith,” I was probably thinking of the Catholic Church. And neither of these possible thoughts had much to do with the origin of the sonnet, which I can voutch for distinctly. In the Bacchae, of Euripides I had come upon . . . words . . . I translated into the line: “It is not wisdom to be only wise”—or too knowing as one might say in prose. Nietzsche had not then been heard of, but the Bacchae is Dionysiac, and I was not blind to that romantic inspiration. The rest of the sonnet was built around that line, which became the second; but I daresay my interest was not exclusively literary; this was, I think, the first of my sonnets (among those published) and, though it seems to be the most popular, it is certainly one of the thinnest in rhythm and diction. But I was certainly in a state of emotional flux in regard to religion, not having yet reached the equilibrium which the twenty sonnets of the first series are meant to lead to. The process, however, took several years.

All this, however, seems to me of little moment. When once anything is given to the public, it belongs to the public, and they are at liberty to find in it what meanings they choose. Whether the author appreciated or not the possible suggestions of his words is a biographical question of no importance in the estimation of the extant work. He may have put into it unawares forgotten or potential perceptions, or even pure collocations of facts or ideas that only a later point of view could disclose to the mind of some other person.

If your interpretation is that my way of seeing and writing is intellectual, I think you are right; but it is intelligence about emotion—intelletto d’amore—so that your critics may be right too.

Yours very truly

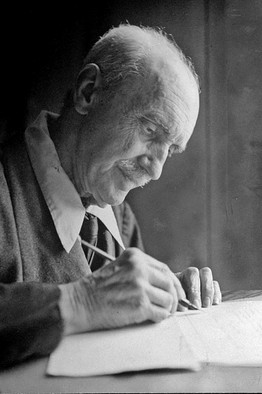

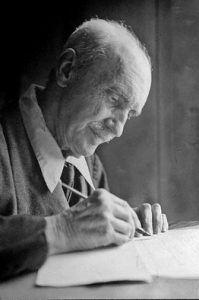

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Six, 1937-1940. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004.

Location of manuscript: Collection of Mrs. Charles (Evelyn) Spiegler, Forest Hill NY.