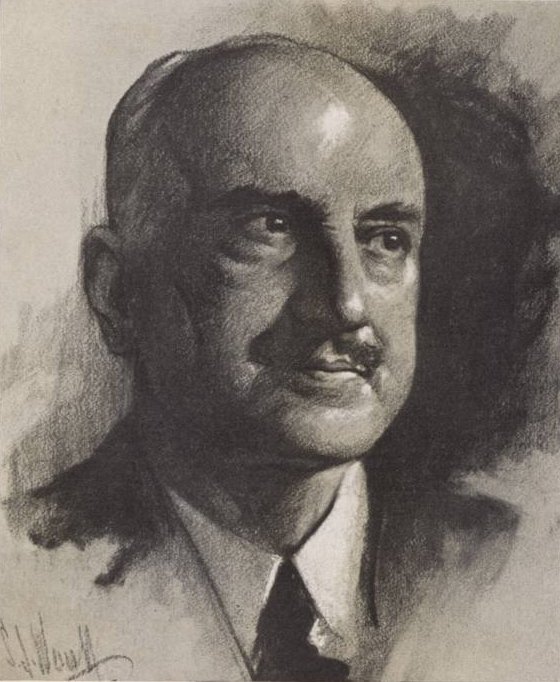

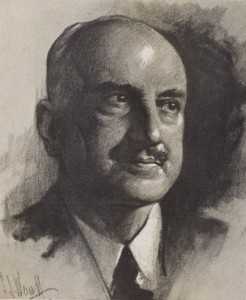

To Hugo Münsterberg

To Hugo Münsterberg

75 Monmouth Street

Brookline, Massachusetts. January 13, [1907 or 1908]

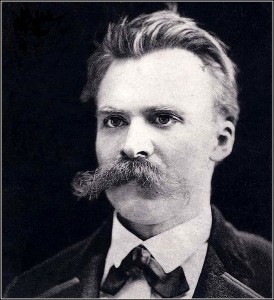

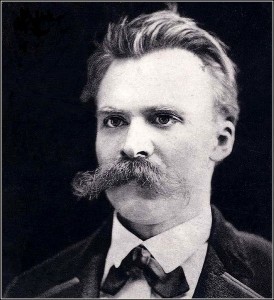

I have not thanked you for “Also Sprach Zarathustra”, which arrived safely, and which I have read with pleasure. The title is also good, although I don’t see that there is anything very new at bottom, or very philosophical, in the new ethics. Has it, for instance, any standard of value by which we can convince ourselves that the Uebermensch is a better being than ourselves? I should like some day to hear your own opinion of this ideal.

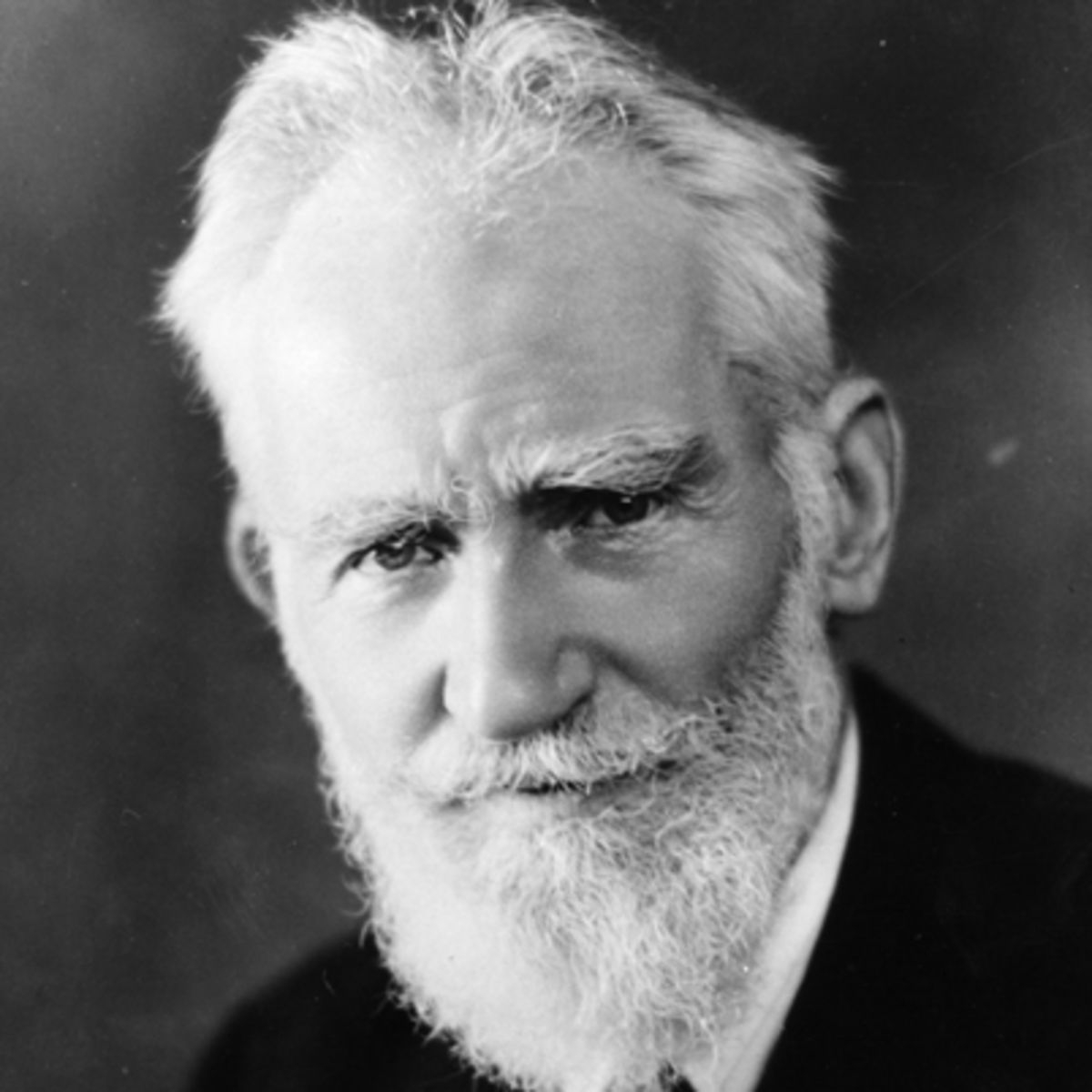

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Unknown.