To the editor of The New Republic

To the editor of The New Republic

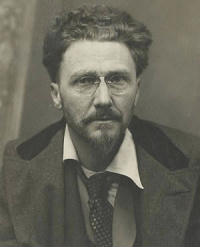

Oxford, England. January 5, [1916]

Protests against your “pro-Germanism” have already had this good effect, that they have made you speak out. May I add another protest, in the hope that it may provoke you to still greater clearness? I think greater clearness on your part is desirable. I have no objection to a German being a German, or a pro-German a pro-German. I read a violently Germanophile Spanish paper regularly and with pleasure. I know that honest men are passionate and that passion is blind. In a clearing-house of opinion. I expect various principles, prejudices, and sympathies to find expression, and I am grateful that my own notions should be courteously admitted there, unshorn and unvarnished. My protest is directed exclusively against your editorial ambiguity. From the beginning the undercurrent of your writing has not been in keeping with your overt opinions. It has been impossible not to feel that if public opinion did not embarrass you you would be far more pro-German than you are. Many an article has begun with an insinuating friendliness towards the Allies that has had a pro-German sting in its tail. If you are really in favor of an inconclusive peace which requires some speedy check to German successes, why do you celebrate the last triumph of German diplomacy and the entry of Bulgaria into the war—somewhat sugaring the pill in another column? And why do you entitle this partisan article “The Debt of Bulgaria to the Allies?” The result can only be that the non-reader should suppose that the article was anti-German, and the confused reader, perhaps, that it was somehow impartial. . . .

What terms of peace have you in mind that would suffice to teach Germany that aggression does not pay, while not inflicting any wound, such as the loss of properly German territory, which would rankle and call for revenge? Could these be less than an indemnity to Belgium, the loss of all the German colonies, the cession of Posen to a reconstituted Poland, and of Metz and the French-speaking districts in the Vosges to France, while the rest of Alsace became a sovereign state within the German Empire? To secure some such terms, if they could ever be secured—terms which would only just save the world from being dominated by terror—a fearful up-hill task, a campaign of months and perhaps years, confronts the Allies, for whose efforts and wrongs your heart does not seem to feel the least sympathy, although they are fighting for what you profess to desire, and for your benefit as well as for their own.

As to an inconclusive peace, which I take to mean the restoration of the status quo ante bellum but with Turkey and the Balkans henceforth under German influence, that would not teach Germany that aggression does not pay, but only, as the Kaiser has said, that everything is not to be attained at one bound, and that something must be left for future generations to conquer.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Two, 1910-1920. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Unknown.

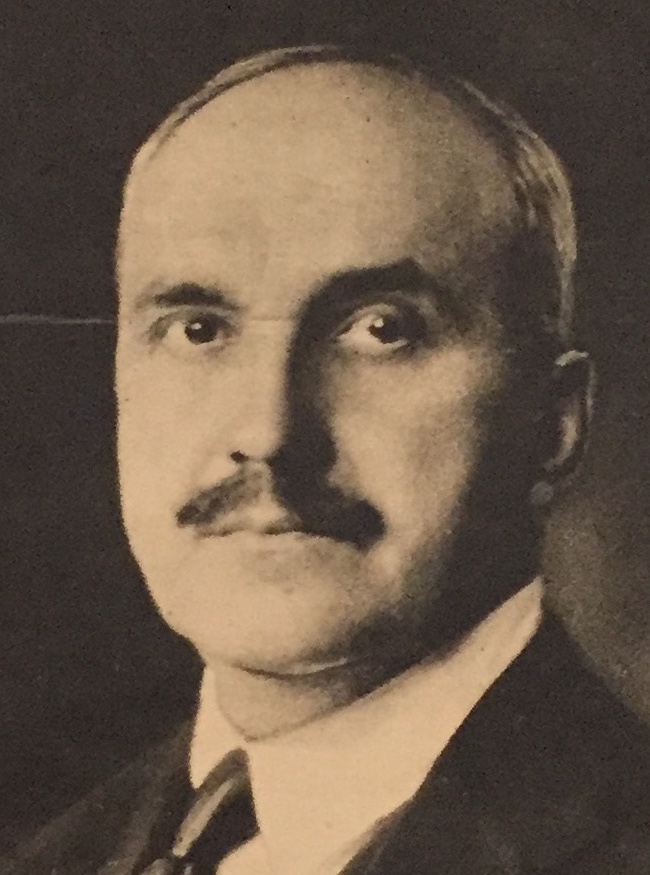

To Boylston Adams Beal

To Boylston Adams Beal