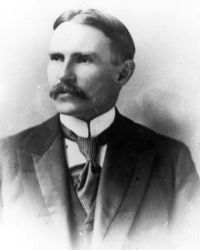

To William Morton Fullerton

To William Morton Fullerton

Berlin. December 28, 1887

I am astonished at your wanting me to send you more stuff à la Rabelais; I certainly can do no such thing professionally and on demand, but only at the call of nature, as it were, or when the spirit (or bowels) may move. But as to your prohibition to be serious, I consider it an insult to a philosopher. I am always serious. It is a great mistake to suppose I am ever in fun. It is the thing that jokes, not I. If this world, seriously and solemnly described, makes people laugh, is it my fault? I am not to blame for the absurdities of nature.

You want my opinion on the axiom that “in a world of squat things a toad would be beautiful”. Well, there is a fraction of an idea in it. It is not the shape or quality of things in itself that makes them beautiful, but the relation of this quality to something else. But to what? Your axiom says, to the quality of the real world—“If things were squat” it says. Now that is wrong. If all things were squat the flatness of the world would be neither a beauty nor a fault. If the world were accidentally less flat than the creative impulse or formative idea would naturally have made it, then things squat would be beautiful indeed. See what I mean? There is a certain ideal dwelling in each of us, which the growth of our minds and bodies under the most favorable circumstances would fulfil. But the circumstances are not favorable as a rule. Therefore the actual result differs from what it strives to be and naturally would be but for external obstacles. Hence ugliness and beauty, as well as all forms of good and bad. The difference between beauty and good in the general and all-inclusive sense, is that beauty is the excellence or perfection of the expression of a thing: It is the adequate presentation of the ideal impulse, whereas virtue is its adequate existence. Therefore virtue is beautiful when represented, but beauty is not virtuous. For beauty being in the image or expression of things, these things need not exist to produce beauty, but only their image need exist—Verbum sat.

Now, having expatiated sufficiently in answer to your question, let me put one to you in turn. What is one to do with one’s amatory instincts? Now, for heaven’s sake, don’t be conventional and hypocritical in the answer you give yourself and me. If you are, you won’t take me in. I know that you don’t really believe that the ordinary talk on such subjects is satisfactory. Let me describe the real situation. A boy lives to his twelfth or fifteenth year, if he is properly brought up, in a state of mental innocence—I don’t say he should not know where he came from when he reached this world, and on which track he travelled thither, nor that he should never have seen dogs stuck together; what I say is that, unless he has been currupted, these things have no meaning and no attraction for him. But soon it is otherwise. He grows more and more uncomfortable, his imagination is more and more occupied with obscene things. Every scrap of medical or other knowledge he hears on this subject he remembers. Some day he tries experiments with some girl, or with some other boy. This is, I say, supposing he has not been corrupted intentionally and taken to whorehouses in his boyhood, as some are, or fallen a victim to paiderastia, as is the lot of others. But in some way or other, sooner or later, the boy gets his first experience in the art of love. Now, I say, what is a man to do about it? It is no use saying that he should be an angel, because he isn’t. Even if he holds himself in, and only wet dreams violate his virginity, he is not an angel, because angels don’t have wet dreams. He must choose among the following

Amatory attitudes.

- Wet dreams and the fidgets.

- Mastibation.

- Paiderastia.

- Whoring.

- Seductions or a mistress.

- Matrimony.

I don’t put a mistress as a separate heading because it really comes under 4, 5, or 6, as the case may be. A man who takes his mistress from among prostitutes, shares her with others, and leaves her soon, is practically whoring. A man whose mistress is supposed to be respectable is practically seducing her. A man who lives openly with his mistress and moves in her sphere is practically married. Now I see fearful objections to every one of these six amatory attitudes. 1 and 6 have the merit of being virtuous, but it is their only one. 2 has nothing in its favor. The discussion is therefore confined to 3, 4, & 5. 4 has the disavantage of ruining the health. 5 has the disadvantage of scenes and bad social complications—children, husbands at law, etc. One hardly wants to spend one’s youth enacting modern French dramas. 3 has therefore been often preferred by impartial judges, like the ancients and orientals, yet our prejudices against it are so strong that it hardly comes under the possibilities for us. What shall we do? Oh matrimony, truly thou art an inevitable evil!

As you perceive, I do not consider sentimental love at all in my pros and cons. It is only a disturbing force, as far as the true amatory instincts are concerned. Of course it has the same origin, but just as insanity may spring from religion, so sentimental love may spring from the Sexual instinct. The latter, however, being intermittent, which religion is not, the insanity produced is temporary. Here is a serious letter for you: now answer it like a man and a Christian—(in the better sense of the word, which is “a fellow such as I approve of”.)

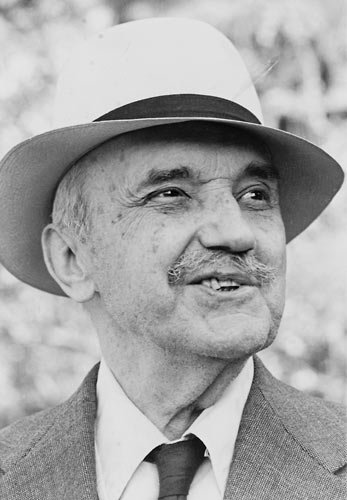

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

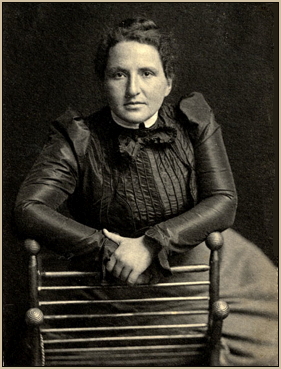

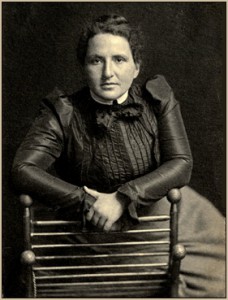

To Gertrude Stein

To Gertrude Stein