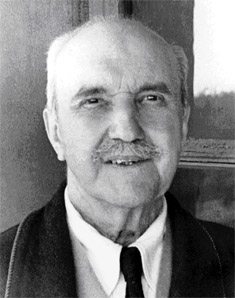

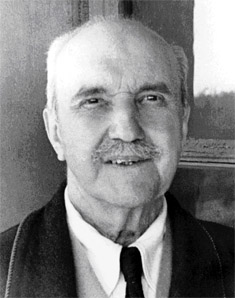

To Cyril Coniston Clemens

To Cyril Coniston Clemens

Hotel Bristol

Rome. Christmas Eve, 1938

My dear Clemens,

All you do and say seems to illustrate a theory which, in my intention, applies only to the last and highest reaches of the Spiritual life, and which I myself am incapable of practising. The truth no longer interests you unless you can turn it into a pleasing fiction. This interview with me I suppose is the same of which, years ago, you sent me a rough draft, where I suggested some corrections in view of that lower and servile criterion, truth. But probably in the interval the force of inspiration has been again at work, and you have produced a sheer poem. . . .

I return your Foreword, as I keep no files, the extreme modesty of my apartment (it’s not very cheap) precludes anything but a waste-paper basket.

I am at work on my last volume of formal philosophy, The Realm of Spirit; but if life lasts even longer, I daresay I shall find it impossible not to keep on writing something or other.

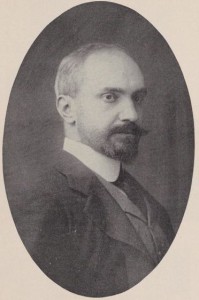

Yours sincerely,

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Six, 1937-1940. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004.

Location of manuscript: William R. Perkins Library, Duke University, Durham NC.