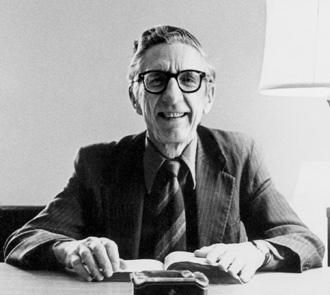

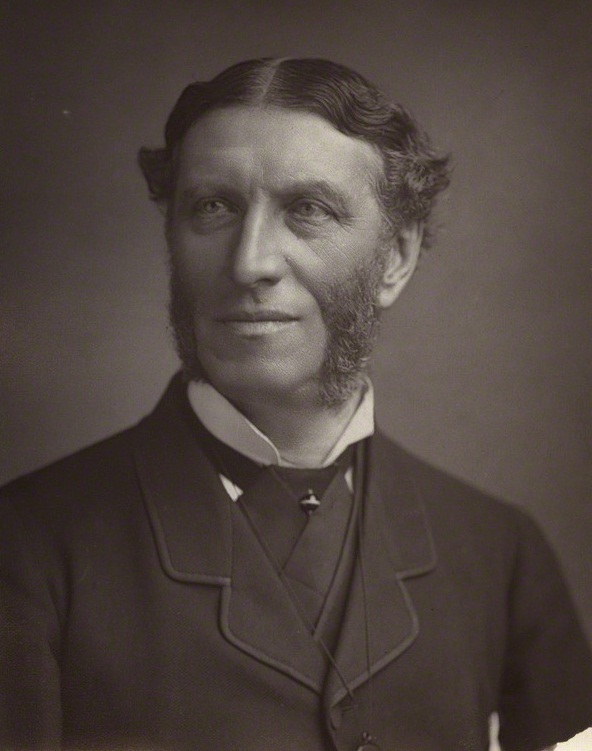

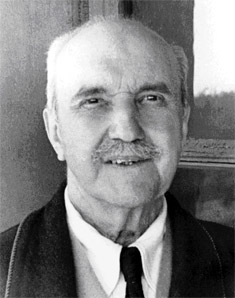

To Frederick Champion Ward

To Frederick Champion Ward

Rome. December 14, 1934

Dear Mr. Ward

Your eulogy of me reads like an old-fashioned epitaph: strictly true to the facts but with no pretense to impartiality. It is very well expressed; and I am sending it to another friend who at this moment is writing an article about me, in case he should like to steal some of your thunder for his peroration. Would you mind?

As to the “subsistence” of essence, have I ever said that it subsists? If so, it was inadvertently. That is rather the neo-realists’ word. In my vocabulary, if anything could be said to “subsist,” or be an essence with a lien on existence and a certain obduracy against contradiction, it would be TRUTH. The compulsion that the triangle exercises on us in forcing us to admit that it has three angles, equal in all to two right angles, etc, is due to the definition and to the essence of Euclidean space, in which that triangle is inscribed. But this whole geometry would be an UNEXEMPLIFIED essence, and would not “subsist,” if nature and experience had not led us to perceive and to study objects in which that essence is found, so that it is a part of the TRUTH about them.

Yours sincerely,

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Five, 1933-1936. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: Unknown.