To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

75 Monmouth Street

Brookline, Massachusetts. December 5, 1906

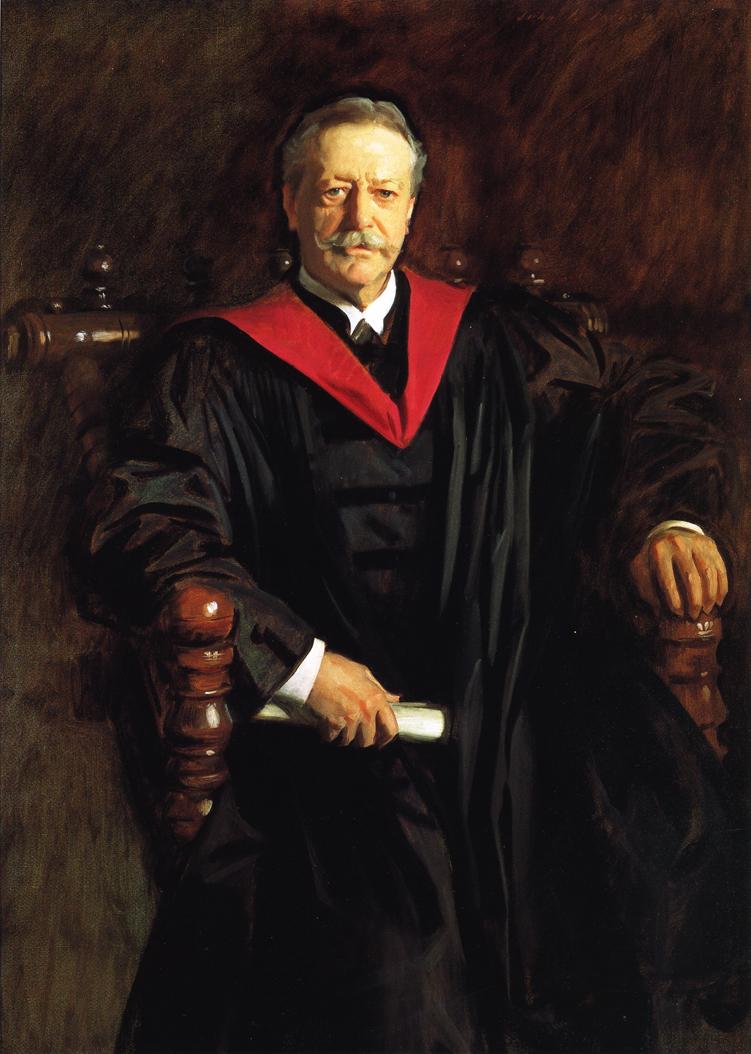

James asked me the other day to go and hear his lecture on “Pragmatism and Truth,” which he said would go over the heads of most of his audience, and he wished to have a few intelligent people to talk to. So flattered, of course I went; but I was disappointed. He made some concessions: logical truth is eternal, and prior to the discovery of it, he says: naturally he doesn’t dwell much on that point. Furthermore it appears that even material truth may belong to unimportant ideas; but who would care for such truth? So that the distinction seems to be accepted, though not made explicitly, between truth simple and pragmatic value or practical importance in ideas. After these concessions, James went on to repeat the old confusions and to protest against the want of imagination of those who take “Pragmatism” at its word. This lecture will not do what James says it is meant to do: it will not clear the air.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY