To Elizabeth Stephens Fish Potter

To Elizabeth Stephens Fish Potter

C/o Brown Shipley & Co.

123 Pall Mall

I Tatti

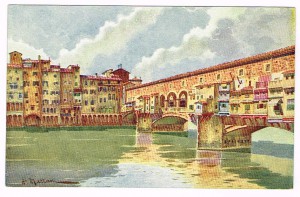

Florence, Italy. November 30, 1912

You have not heard, perhaps, that my mother died soon after I left America. It was not an unexpected loss, and in one sense, as you know, it had really occurred long before, as my mother had not been herself for some years. Nevertheless, her death makes a tremendous difference in all our lives, as she had always been the ruling influence over us. She had a very strong will and a most steadfast character, and her mere presence, even in the decline of her faculties, was the central fact and bond of union for us. Now, everything seems to be dissolved.

. . . .

I was forgetting to tell you what is perhaps the only important fact—that I have resigned my professorship altogether, and don’t expect to go back to America at any fixed time. As you know, my situation at Harvard has never been to my liking altogether, and latterly much less so, because I began to be tired of teaching and too old for the society of young people, which is the only sort I found tolerable there. The arrangement I had made with Mr. Lowell for teaching during half of each year, I should have carried out had my mother lived; but it was never meant, in my own mind, to last for ever. Now, it seemed that the moment to make the change had come. My brother assures me that I shall have a little income that more than supplies my wants; Boston, with no home there, with no place to dine in night after night but that odious Colonial Club, is too distressing a prospect. Here, on the other hand, everything is alluring. My books (the only earthly chattels I retain) are at the avenue de l’Observatoire; that is my headquarters for the present. Meantime I am looking about, and if some place or some circle makes itself indispensable to my happiness, there I will stay. Intellectually, I have quite enough on hand and in mind, to employ all my energies for years.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Two, 1910-1920. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA