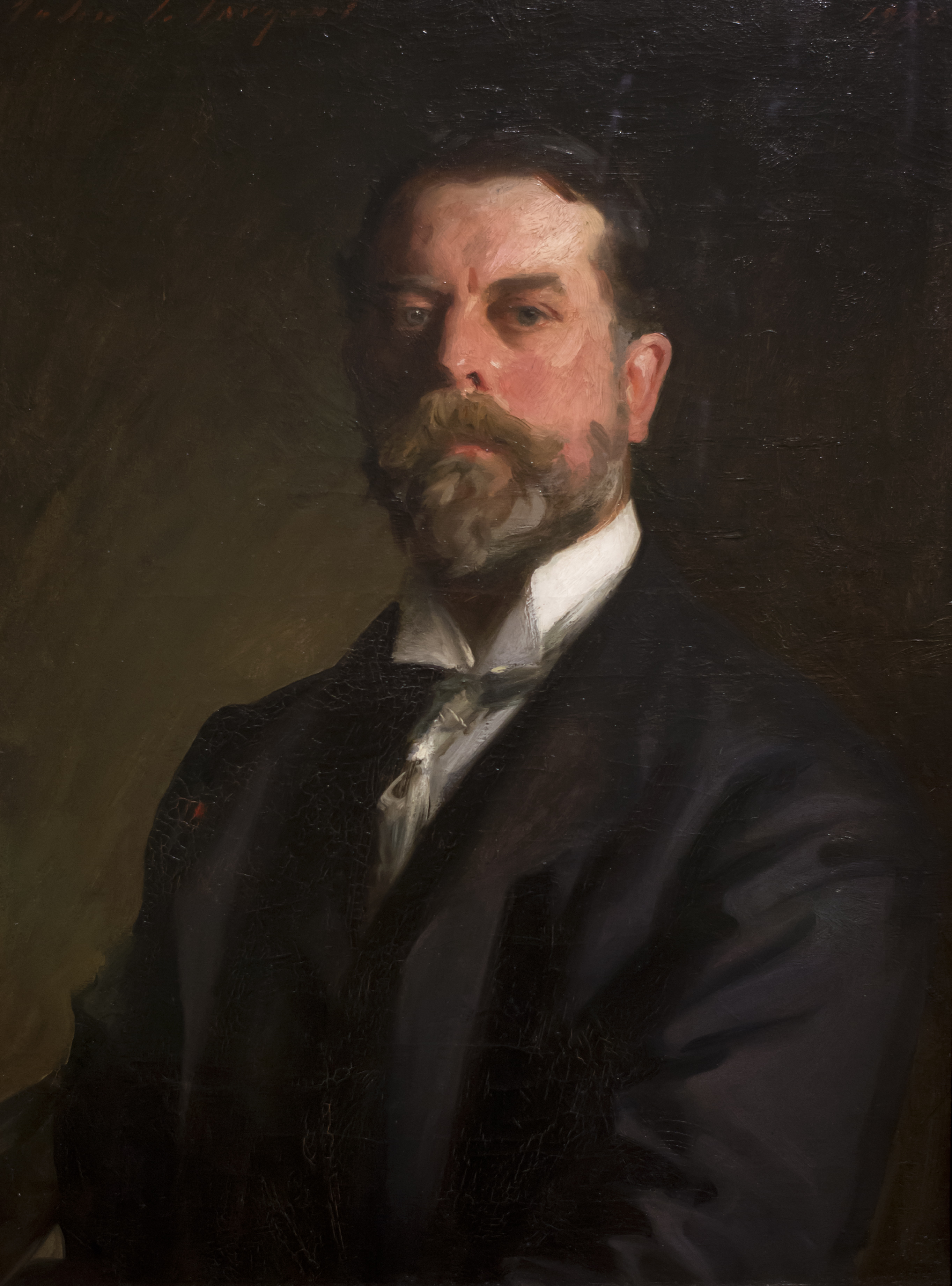

To Henry Ward Abbot

To Henry Ward Abbot

Berlin. February 5th 1887.

I am afraid I can’t save you from solipsism by argument, but I don’t regret it much, since it is easy for you to save yourself from it by action. Philosophy, after all, is not the foundation of things, but a late and rather ineffective activity of reflecting men. It is not the business of philosophy to show that things exist. You must bring your bullion to the mint, then reason can put its stamp upon it and make it legal tender. But if you don’t bring your material, if you don’t give reason your rough and precious experience, you can get nothing from her but counterfeit bills—nostrums and formulas and revelations. Now a man’s stock of experience, his inalienable ideas, are given facts. His reason for holding on to them is that he can’t get rid of them. Why do we think at all, why do we talk about world, and ideas, and self, and memory, and will, except because we must? You say that you are will, and that your existence as such is given by immediate intuition. That is a rather complicated fact to be foundation of knowledge. If however it is a fact which you cannot doubt, it is a perfectly good foundation. Any fact you cannot doubt is—any inevitable idea is true. Now, if you imagine a being whose stock consists of this intuition of itself as will and of a world as ideas, I think you will be unable to make that being believe in other wills. That being would not rebel against solipsism; anything else would be impossible for it. It happens that we are not such beings; our inevitable ideas are not a self as will and as a reservoir of images. This notion is at best a possible one for us—possible together with innumerable other notions. If you find, however, that you can actually get rid of all other ideas and live merely on this stock, nothing can prevent your trying the experiment. Be a solipsist. Say “My own existence as will and the existence of a world of ideas in my mind—these I cannot doubt. But this is all that I find it necessary to believe. With this faith I can do my business, make love to my sweetheart, write to my friends, and sing in tune with the spheres.” If you can do that, what possible objection is there to your solipsism? Surely none coming from a sincere and disinterested philosophy. But can you do it? That is the question. I suspect that your business and letterwriting, your love and the music of the spheres, would fill your mind with other notions besides those first inevitable ones, and make these other notions no less inevitable. They would increase your inalienable stock of ideas and make your philosophy unsatisfactory, not because it had not accounted for the ideas you brought originally, but because you had more ideas now which it would need a different philosophy to account for. You must keep one thing always in mind if you want to avoid hopeless entanglements: we do not act on the ideas we previously have, but we acquire ideas as the consequence of action and experience. If you habitually treat these visions of other men as if they were your equals, you will therefore believe that they have will and intelligence like yourself. Now, your own survival in the world depends on your social relations, so that solipsism is a practically impossible doctrine. It could not flourish except among isolated beings, and man is gregarious.

What do you mean by self? What do you mean by existence in the mind? So long as you believe in a self-existent world of objects in space, you know what you mean by the objects in the mind. You mean those objects which are not self-existent in space. If, however, you abandon (or think you abandon, for I think the argument proves you have not really done so) the notion of objects self-existent in space, your phrase “objects in the mind” loses its meaning, since there is no longer any contrast between two modes or places of existence, one the mind and the other external space. Objects now do not come into the mind, they merely come into existence. Ideas, if they have no real objects, are real objects themselves. The quality of independence, unaccountableness, imperiousness which belonged to the things now belongs to the ideas. They are yours—they are in you—no more than the objective world was before. This is what makes idealists invent a universal consciousness in which the ideas eternally lie: if this world is to be an idea it has to be an independent, objective one. For see what the alternative is: There shall be only my own personal ideas—but how far do I reach? Did the world begin with the first sensation I had in my mother’s womb? Evidently my foetus is an idea in my mind quite as foreign to me as you are. Did the world begin with the first idea I can remember I had? But in that case the world has begun at different points, since sometimes I can remember an event which happened when I was four, but then I could remember what happened when I was three. Or shall the ideas in existence be only those I have at this moment? But this moment is nothing—it is a limit, it contains no ideas at all. Ideas are alive, they grow and change, they are not flashed ready made into the darkness. My ideas are therefore indeterminate in quantity and duration. As impossible as it is to say where one of them stops and another begins, so impossible is it to say where my consciousness becomes different from that of my mother, or wherein it is different from that of other men now. When in a crowd, in a contagion of excitement, we do not think in ourselves only but in other people at the same time. The bodies are separate but the consciousness is not. The result is that I have more ideas than I know; I can’t trace them downward to there depth and full content, nor outward to their limits. In what sense, then, are my ideas mine? Only as the left side of a street is to the left; I only can talk of myself because I think of you, of my ideas because I postulate yours. If I existed alone, I should have no self, as the theologians very well saw when to save the personality of God the made him three persons. That is about all I have thought about solipsism. You say, or hint, that you are resigned to being an egotist and egoist, but not to be a solipsist. The things are but two sides of the same; it is harder to deny the existence of other men in thinking than in willing, be cause in thinking we depend so much on words, and books, and education—all social things, while in willing we are more independent, at least we feel more independent, for in reality we are perhaps less so. The more fundamental part of us is where we have more in common, and where influences are more easily exercised. It is more easy to influence than to persuade.

Strong and I propose to go to England about the first of March, so that when you write again you had better address care of Brown, Shipley & Co. It is possible I may stay in England the rest of this year, but I cannot tell until I have seen the place. I naturally have to go with Strong, as our partnership is of mind and pocket; he is rather sick of this place because one is so isolated in it. Bad thing for a would be philosopher to complain of isolation. Poor Strong! he is like a man up to his middle in cold water who hasn’t the courage to duck. The cold water is the antitheological stream. Hoping all this is nothing but your idea I am sincerely your friend

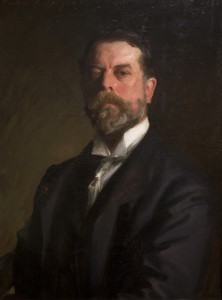

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Butler Library, Columbia University, New York NY.

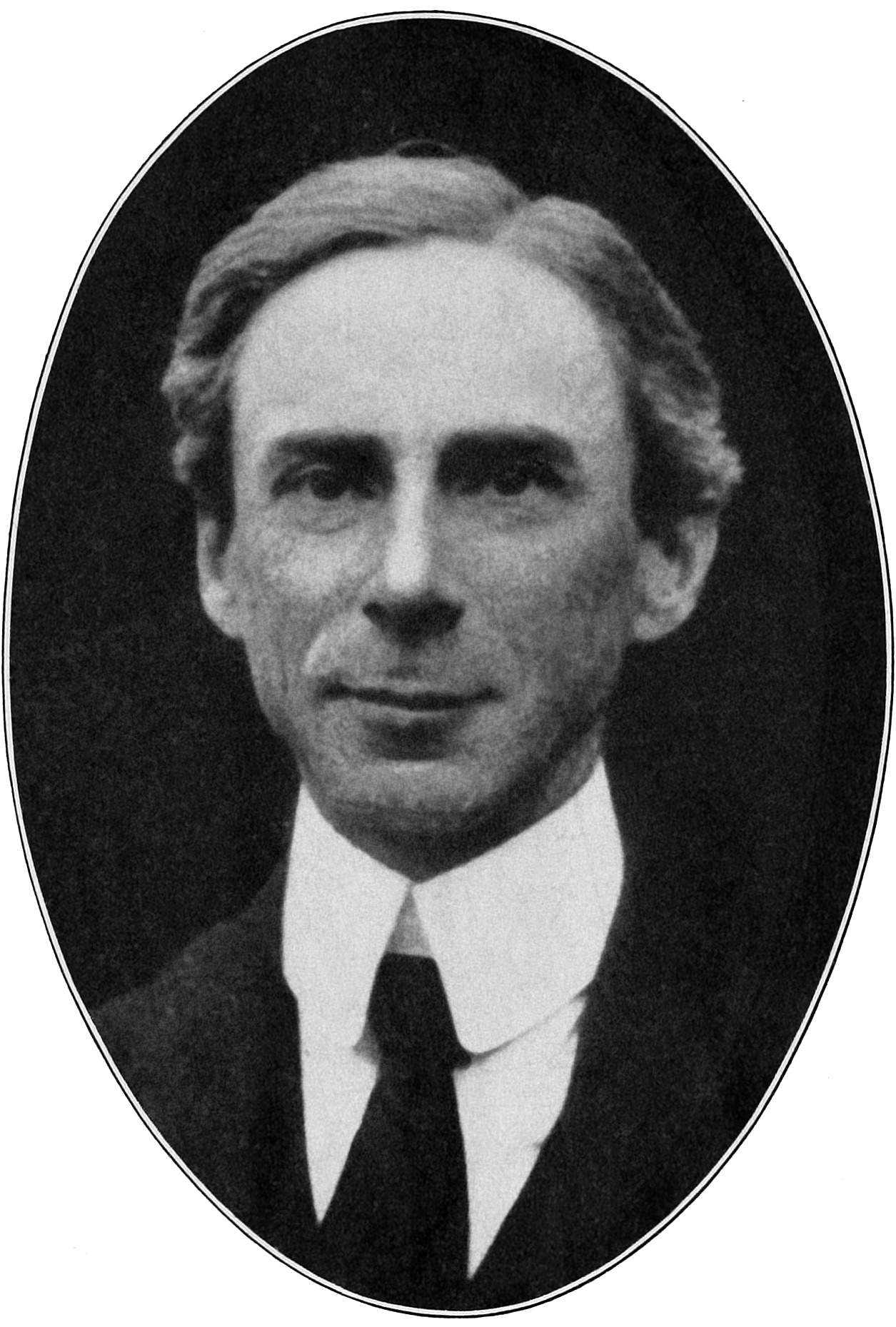

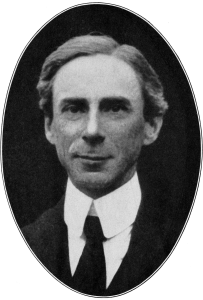

To Bertrand Arthur William Russell

To Bertrand Arthur William Russell