To John W. Yolton

To John W. Yolton

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. May 2, 1952

Argument has never been, in my opinion, a good method in philosophy, because I feel that real misunderstanding or difference in sentiment usually rests on hidden presuppositions or limitations that are irreconcilable, so that the superficial war of words irritates without leading to any agreement. Now in your difficulty with my way of putting things I suspect that there is less technical divergence between us than divergence in outlook upon the world. And I am a little surprised that you should attribute to official America today an ambition to prevent Russia from establishing labour-camps, etc. All that I should impute to American policy is that it fears the eventual spreading of Russian methods over the whole world. This is what the Russians mean to do, and gives a good reason for resisting, not for abolishing, them; which last, as far as I know, nobody intends.

It is what people intend or actually do that interests me, not what they think they or others ought to do. Therefore in my books, at least in the mature ones, I am not recommending a rational system of government but at most considering, somewhat playfully, what a rational system would be. And in considering this, I come upon the distinction between the needs and the demands of various human societies. The needs and the extent or possible means of satisfying them are known or discoverable by science. So medical science may prescribe for all persons the operations, cures, or diets that it discovers to conduce to health. And so, I say, economic science might discover how best territories may be exploited and manufactures produced, in so far as they are needed or prized. There should therefore be a rational universal control of trade, as of hygiene; and both involve safety for persons and their belongings. The police, communications and currency should be universal and international; and the limits of wages and profits in all economic matters should be equitably determined by economic science. There could therefore be no strikes, monopolies, labour-camps or capitalists, and a scientific communism would reign in most of the things that now cause conflicts in government and between nations. But the justification for this autocracy in the economic sphere would be that only the force majeure of nature imposed on mankind in their ignorance; whereas, imposed by doctors of science, it would prevent all avoidable distress and unjust distribution of burdens.

With this foundation laid in justice and necessity all races, nations, religions, and liberal arts would be allowed to form “moral societies” having, like “Churches” among us now, their special traditions and hierarchies and educational institutions. Each would have an official centre, as the Catholic Church has the Vatican, but need not have any extensive territory. I am always thinking of the East where great empires have always existed, controlling in a military and economic way a great variety of peoples, and preserving a willing respect for their customs. It does not occur to me to say whether cruel institutions should be suppressed from outside if odious to other peoples. Violence, in any case, would be impossible, since that could be exercised, in the name of Nature, only by the rational universal economic authorities, and all the “moral societies” would be unarmed. They would not be able to prevent rebels within their society to leave it; nor would they be compelled to unite or compromise with any other moral society. They might mingle as Jews, Moslems and Christians mingle in the East when they have a good impartial government, such as Alexander planned to establish and the Romans and in a measure the Moslems have sometimes carried on.

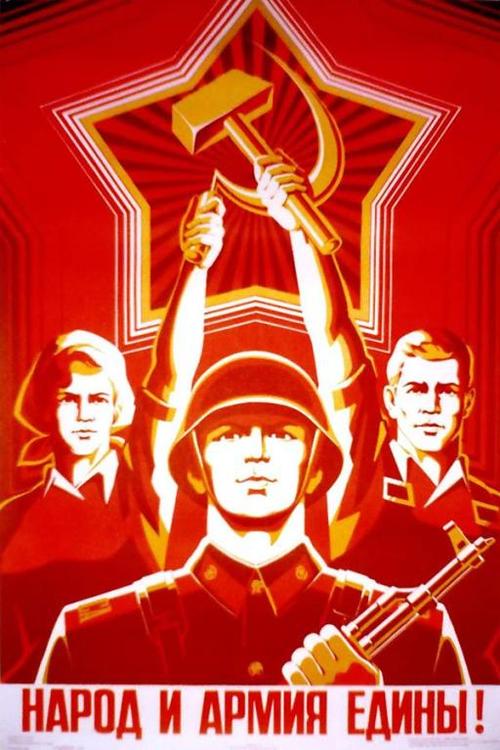

I suspect that you naturally think of “moral” passions as guiding governments and instigating wars. You expect “ideologies” to inspire parties, and parties to govern peoples. All that seems to me an anomaly. And it is not the intellectual or ideal interests invoked that really carry on the battle, but the agents, the party leaders, who have political and vain ambitions. Mohammed was a trader before he decided to be a Prophet, dictated to by the Archangel Gabriel; and it is already notorious that in Russia the governing clique lives luxuriously and plans “dominations” like so many madmen. It is human: and the gullibility of great crowds when preached to adroitly or fanatically enables the demagogues to carry the crowd with them. There would be no “communists” among factory hands if they knew their true friends.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: Unknown