To Nancy Saunders Toy

Hotel Bristol

Rome. Nov. 12, 1931

I feel so much the continual death of everything and everybody, and have so learned to reconcile myself to it, that the final and official end loses most of its impressiveness. I have now lost almost everybody that has counted for much in my life. You are almost the sole exception: because Strong, a lifelong if not at all a romantic friend, has developed an attitude towards me which is as unpleasant as it is unexpected. I have become, philosophically and intellectually, his bête noire.¹ Personally we are still good friends: we keep up appearances, and this summer and autumn he has actually followed me to Cortina and to Naples (where I have been for a month) and spent a few days near me at each place. But there is always a tension beneath. He has reverted to strict Puritanism in his moral sentiments, and regards his father (who had a very red nose and married again at 85) as a model of human character. And he has recovered also all his American pride, and feels that it is unseemly and unworthy that I shouldn’t endeavour to think and write like other American professors. My theory of “essence” is anathema to him, although for some years he innocently adopted it: he doesn’t like my last little book on The Genteel Tradition: and as to the novel, of which at his request I showed him the first three chapters, he told Cory that it ought to be burned. Cory has no doubt been the accidental cause of a part of this transformation. Cory at first was my friend only, and helped me with The Realm of Matter. When this was finished I was going to let him go home and look after himself: but Strong said he envied me such a secretary, and asked him to stay and work with him. And quite naturally, I suppose, Strong began to resent the fact that, in our technical divergencies (which have always existed, and not caused any serious trouble) Cory should follow me rather than himself: and he began to work to convert Cory, partly by persistently and overbearingly imposing his own view, and partly by doing all he could to disparage and condemn me. Isn’t it sad? Let me give you a sample of the process. In one page of an essay on Whitehead which Cory has written—he is partly Irish and has warm feelings—he had said that he was a “disciple” of mine, had called The Realm of Matter a “great book”, and had used the term “essence” once. Strong, in reviewing the essay with him, didn’t rest until “disciple” was changed to “person influenced by”, “great book” to “recent work”, and “essence” to “datum”. If you asked Strong how he could be so mean and ungenerous to his oldest and almost his only friend, I think he would say that he felt it his duty to protect Cory from making unfortunate slips which would discredit him as a critic among the professional philosophers: and that nobody would take him seriously if he began by saying that he was simply following me. There may be some truth in this, and I don’t regret at all that Cory should correct his essay as required. But what do you make out of such want of feeling, and such a bitter undercurrent of tyranny? Poor Margaret! I understand now better than ever what she must have suffered. Cory himself is very unhappy about it all: but what is he to do? Strong is supporting him, and has put him in his will.

I hope I am not indiscreet in telling you all this, but it is very much on my mind, and as I said, you are the only true friend left to

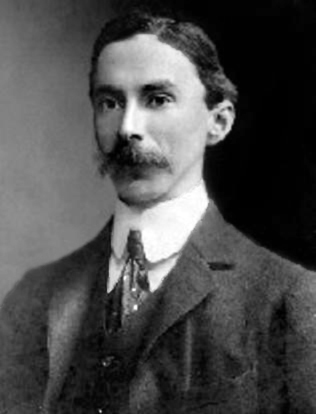

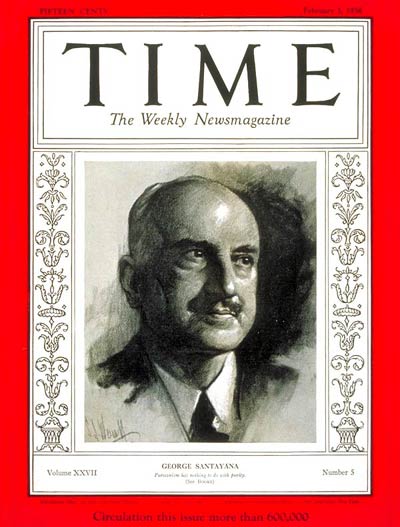

G. Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Four, 1928-1932. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA