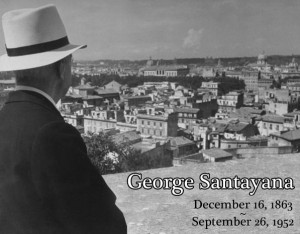

To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

London. September 27, 1932

Dear Strong,

Your letter about Cory came at an unlucky moment when he was laid up with a touch of the “flu”, and had received a nice letter from the Journal of Philosophy, saying that his paper on Whitehead was accepted and that Whittredge had read it and liked it very much. Thus, for the moment, two of the points of your dissatisfaction were a little blunted, in that he seems to be really delicate, and to have advanced one step towards establishing himself in the public eye as a philosopher.

I feel hardly competent to advise you, from your point of view, about the wisdom of continuing to support Cory. If you regard him merely as a philosophical investment, I am not at all confident that he will ultimately justify your confidence: he has perception and an occasional intense spurt of industry, but on the whole his temperament is Irish and poetical, he is self-indulgent and capricious, and resents any attitude towards himself that is not one of complete disinterested sympathy and trust. For my own part, I feel perfectly willing to take him at his own valuation, and run the risk of wasting my sympathy—not entirely in any case, since I find him a pleasant companion, and a link with the younger intellectual generation.

It seems to me that, in your place, I should wish to continue to encourage him, in the hope that, as the years go by, he may prove more and more valuable to you as a disciple and friend. But I think, in that case, the experiment is more likely to be satisfactory if you leave him free to choose his residence and way of living, and above all the tone of his opinions, as his own temperament dictates. A check-rein is the worst possible harness for a colt of his mettle. Of course you should expect him to come and see you frequently, and to continue studying philosophy with a serious mind. But beyond that, I think pressure will be rather wasted on him. For instance, he might go on living in England, but remain shut up in his bedroom, reading Proust and Pater and T. S. Eliot: evidently he might as well have read them sitting in the sun in the Riviera. I myself have always wished that he should mingle with refined English people of the intellectual type—like old Bridges, for instance, or Bertie Russell But it has to be, if at all, in his own way: and you and I are too old, and too much out of the world, to expect him to choose his best friends in our small circle.

As to his returning to New York—that too was originally my idea of what might be best for him. But isn’t it rather too late now? If you drop him, and he has to do that, it might be the making of him: but I certainly should still feel responsible for his future after having tempted him to remain so long out of his country and almost idle. Yours ever G.S.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Four, 1928–1932. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY

To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong