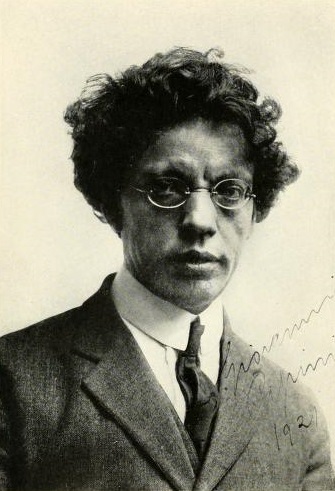

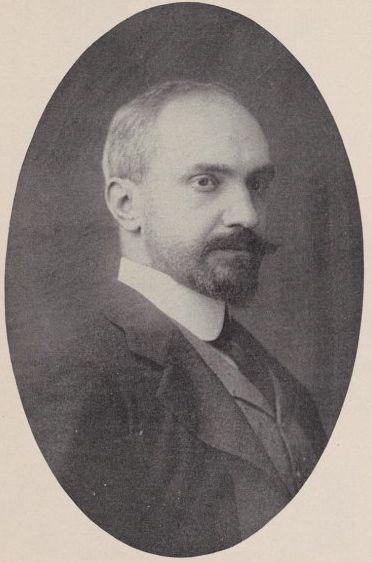

To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

Address: C/o Brown Shipley & Co. London.

Box Hill, Surrey, England. July 26, 1905

Please excuse this sheet of fool’s cap: I have no frivolous note-paper at hand and the contents are going to justify the pomposity—and perhaps the name—of the medium.

I had no notion that in submitting my innocent foot-note to your previous censorship I was asking you to aid me in any attack upon your doctrine. Perhaps, if you would only allow me my language, your doctrine would be almost my own. What I wanted was, not to misrepresent you. Now, my prudence seems to have its reward, for apparently I did misrepresent you in supposing that you made human thought “a view or result of much mind-stuff in fusion.” Your correction, if I understand it, brings up a point quite new to me. Mind-stuff contains relations between its own parts; and adding these relations together you get a sort of continuum given within mind-stuff, although the total landscape is only represented, and not within mind-stuff anywhere in an absolute sense. The partners hold hands, so to speak, but no one contains the whole minuet. Is this your idea? If so, it seems to me you are jumping from the frying-pan into the fire. For the “extensity” of sensations, or their essential lapse, is a character of their object; and this is a material character. If the extensity of a sensation can be predicated of mindstuff itself, then mind-stuff is extended! You would not maintain that, I suppose; yet how can you avoid it? Your inclusion of relations within mind-stuff either lifts mind-stuff into mind, its object acquiring the relations observed and it itself being lifted to a transcendental sphere and made an act of apperception or (as my book will call it) an intent; or else this inclusion reduces it more obviously than ever to matter. “Isn’t this what Bergson (whom I am surprised to hear you invoke, when his dichotomy of Matière et Mémoire is all on my side) tries to do, making the immediate material, and the reflective possession or representation of it spiritual and eternal—which is more than I can agree to. However, with many thanks for this information, I hasten to correct my foot-note and will make it read: “a certain bulk of sentiency in flux, illustrating spatial and temporal relations, and not merely representing them.” Is this better? There will be time to make further corrections, if I have gone wrong. I will also correct the phrase about “doing honour to spirit” and substitute “thinking to give spirit a more congenial basis by making it its own stuff, thereby forgetting that spirit is expressive and, being expressive must have a different status from that of its basis or subject-matter.” The style suffers: but I, too, am ready to make any sacrifice of personality on the altar of truth. I may, however, think of a better wording than that above.

Where I can’t accept your criticism is in respect to the word matter. Why should Berkeley’s ignorance of Aristotle be allowed to infect more generations? Matter is in a way approached from without, since it is potential and inferred, as every substance must be, including mind-stuff, or as truth is. But it means the surd in things, the existential strain that makes them be here and now, in this quantity and with this degree of imperfection. I have a previous note on the use of this word, too long to quote. You will see it when the book appears, for on this subject I know what I am talking about and speak quite deliberately.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]–1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY.

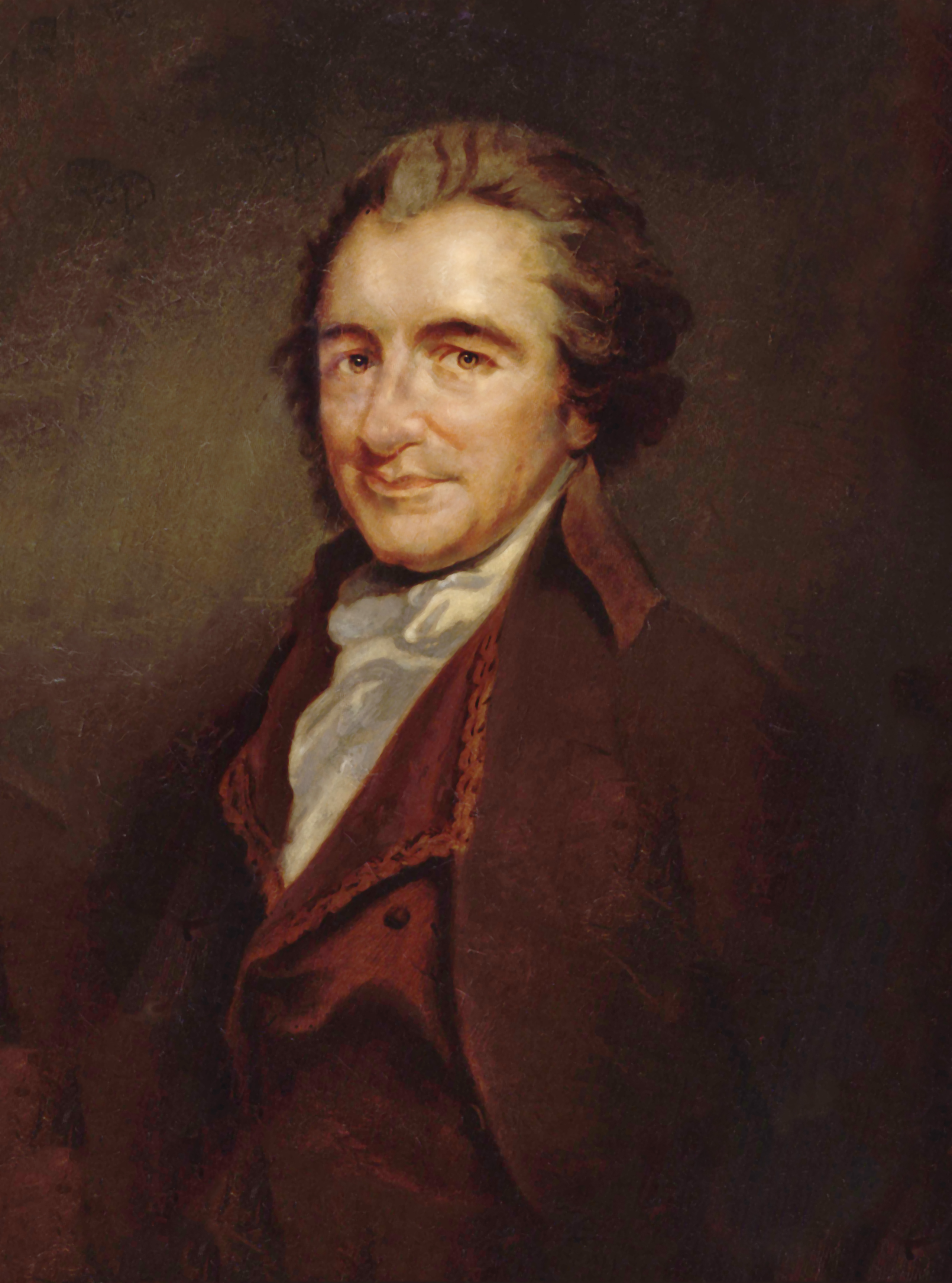

To [Henry Ward Abbot]

To [Henry Ward Abbot]