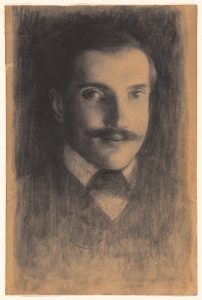

To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

Ávila, Spain. July 22, 1890.

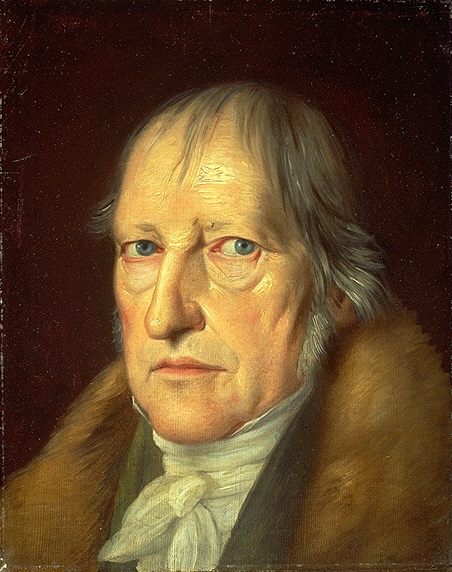

As to my plans for the future, they are simply to take up and put up with what offers. I am content to go on with lectures at Harvard indefinitely, if they want me. If they don’t, something else will probably present itself. Harvard has many attractions and advantages, the main one being the great freedom you enjoy. Royce last year annoyed me a good deal. I took a course he gave in Hegel’s Phenomenologic which was appalling, and he seemed to be bent on converting me to absolute idealism nolens volens. But Royce, although sometimes such a bore, is a good and kind man, and very appreciative, and generous to me. With Palmer I get on well. We never discuss anything. I treat him as if he were a clergyman, and he is nice to me. With James I have much more sympathy, both personal and intellectual I think he is beginning to understand that I am not a dreamer and obscurantist, and that, in spite of certain literary leanings, I am capable of facing questions of fact and evidence without repugnance —and or parti pris. Everett has also become a friend of mine.

Peabody is the only member of the philosophical Committee that seems to think me dangerous and highly improper. The President looks upon me with favor, because as I am told, he thinks I may contribute to the college a little of that fresh air and blood of which it stands in so much need. It is really sad to see how mediocrity Germanised rules supreme there. For all these reasons I think my position at Harvard tolerably stable and honorable. I study to keep apart from the Germans. Royce is the only one I cannot avoid. . . . Altogether I had a good time, and enjoyed what I never had cared for before, the air and sunlight, food and drink, and the consciousness of life—rational and irrational—about me.

By the way, I saw your former chief Prof. Schurmann this winter. He came to sound the Cambridge philosophers on the subject of founding an American philosophical journal. I was glad to see that his project met with universal discouragement. Since that time, however, Royce has afflicted me with the subject again, and even asked me if I would be willing to undertake the editorship. I gave an evasive answer, for I should not particularly object, if the thing were perpetrated at all, to have some influence in selecting the kind of ignorance and presumption that should appear in it. A little less Hegelian drivel might thus be administered to the feeble minded public. But I hope the plan may collapse. If anything is written in America worth publishing it can go into Mind, which certainly has room for it. I do not attach great weight to Schurmann’s objection to this plan, viz. that in two weeks a number of Mind is behind the times, and we must have a pure American truth, served hot every morning like the biscuits. Schurmann, indeed, appeared to me like a wise man of Philistia, rhetorical, vulgar, and self-asserting.

I have not left room for much discussion of Ethics. I admit all you say about the inherent lack of authority in a “demand”. All the stars laugh at a demand. I have no notion of making it sacred. And I also admit (and here I am glad to see we have been moving in the same direction) that it is by their consequences that the lawfulness of actions should be measured. There is no practical seriousness in a system that poopoos consequences, and strings phrases together about self imposed, self evident principles. But I would have you observe, in excuse for my former insistence on demands as the basis of Ethics, that our judgments about good and bad consequences are inspired by instincts which may very properly be called our natural demands. The reason why I should not do a particular atrocity, e.g. maintain protection or Hegelianism, is the consequences. But why is poverty, the consequence of the one, or idiocy, the consequence of the other, an evil? Because of my natural demand, and that of my fellows, for wealth and for intelligence. And so it still seems to me, after heartily admitting all you say, that our actual and spontaneous demand for one kind of existence rather than another is the ultimate basis of all values.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]–1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY.

To William Archer

To William Archer