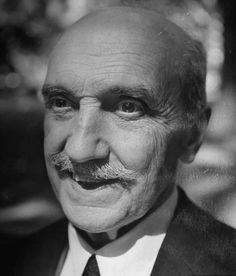

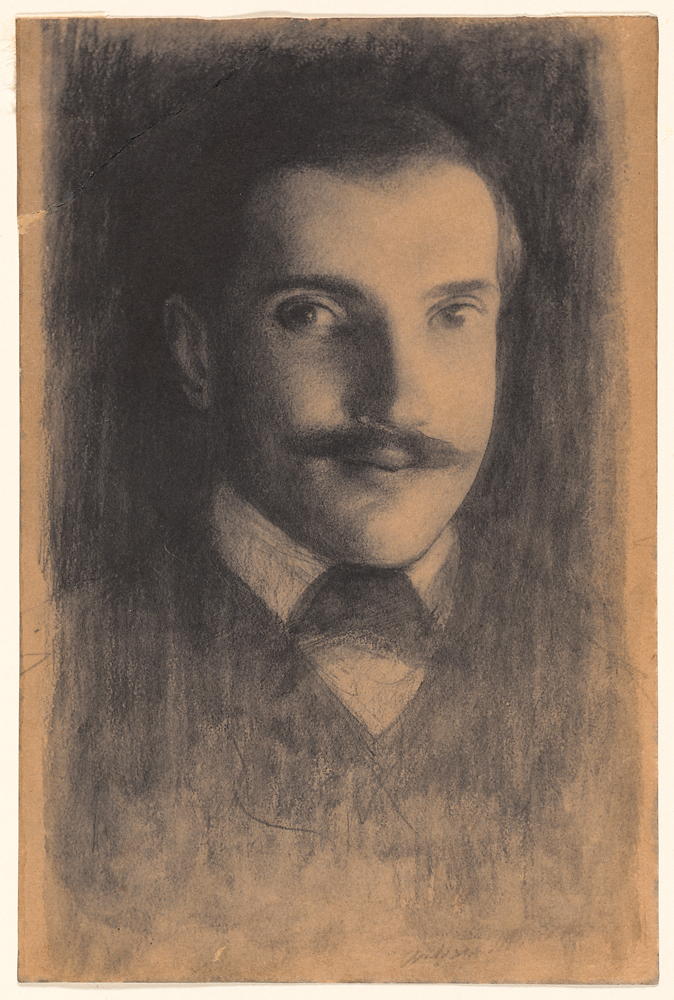

To Rimsa Michel

To Rimsa Michel

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6,

Rome. July 8, 1950

Dear Mr. Michel

Your well typed Essay, in its flexible black leather binding, added to certain melancholy notes in your letter, made me feel at once that you were a young man of feeling, who liked to work like an artist: and I began to read with a little apprehension that you might be only that—or perhaps a sentimental lady: (your name not being decisive (for me) on that point) and that you might really be impossibly mystical or poetical, like the theosophists. I have now finished reading the whole and find nothing of the sort, even at the end. You detach the meaning I give to “essence” clearly and soberly. In reading, for some thirty pages, I found only a faithful enough echo of The Life of Reason, as conceived in New York, and was uneasy only at what seemed an exclusive acquaintance with that and with my works in general, as if I were not a man but a text-book. This misgiving was corrected afterwards, as far as sympathy with my later writings is concerned. You not only know them all well but you are the only critic I have come upon who understands the character of the change that came over my manner. I have explained this, with a reference to my circumstances and uncongenial philosophic teachers, until I went to Germany, in the Preface or Introduction written for the one volume edition of Realms of Being.

This leads me to the first jolt which I felt while so pleasantly conveyed in your carriage: your sharp objection to the word “Realm”—because it is not republican. Have you never heard that natural history, until the other day, divided nature into the Mineral, Vegetable and Animal Kingdoms? I didn’t know that this word, like the word “essence” was taboo in America. I braved the inevitable prejudice in the case of “essence” because it is the only proper word for what I had in mind, and traditionally opposed to “existence”, like “form” to “matter”. But the reading that is now done, beyond “majors” in colleges, or at home, is very limited in proportion to what everybody was expected to know a hundred or even fifty years ago. “Culture” is collapsing into compendia and school-books, as at the beginning of the “dark ages”. (You must consider that I am very old.)

. . . The chief point that has arrested my attention in your interpretation is the relation, discussed at the end, of the good to the rational or moral. You understand perfectly how I get “beyond good and evil” not by abolishing or even modifying their commonsense reality, but by transcending them in view of their relativity. The last words of Dominations & Powers, the book—my last book—just finished, are these; “Comparison (of values) presupposes a chosen good, chosen by chance. The function of spirit is not to pronounce which good is the best but to understand each good as it is in itself, in its physical complexion and its moral essence”.

The quality of your essay is so unusually good, and good in the higher insights, that I should like to know more of your “other failures” and of the circumstances that can have occasioned them. Why should you be unhappy with so much capacity for discernment? And I should judge that it has not been material difficulties that have stood in your way.

Yours sincerely

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948–1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: Unknown.