To Rimsa Michel

To Rimsa Michel

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo. 6

Rome. September 22, 1949

Dear Mr. Michel,

Since I seem to be responsible for turning you into the wilderness of philosophy, I suppose I ought to help you to get out of it, but I am not sure that there was ever any “Humanism” in me that I have given up. Certainly I have given up talking about the superiority of rational to inspired poetry, or vice versa. I am not a dogmatist in morals, which for me include both aesthetic and political judgments; and in judgment of love or taste I am entirely a humanist in the sense of thinking that the human psyche is, in each case, the only possible judge; and naturally each psyche the only possible judge, for it own satisfaction, of the satisfaction that it finds in the satisfactions of the others. But what I don’t believe, or seriously ever did, is that any human authority, private or social, has any absolute control or jurisdiction over what “ought” to be done or praised. In fact, I have been attempting, in my old age, to re-educate myself in the matter of poetry, so as to be able to appreciate the “modern” forms of it. But I have never so much enjoyed and admired the old Latin poets as of late years: and have actually translated, at great expense of sleepless hours, a bit of the 3rd Elegy of Tibullus, Book I, which will come out in a new English little Review which will begin publication before long. The editor writes that my diction is still traditional but that the poem is a modern poem. So you see I practice what I preach.

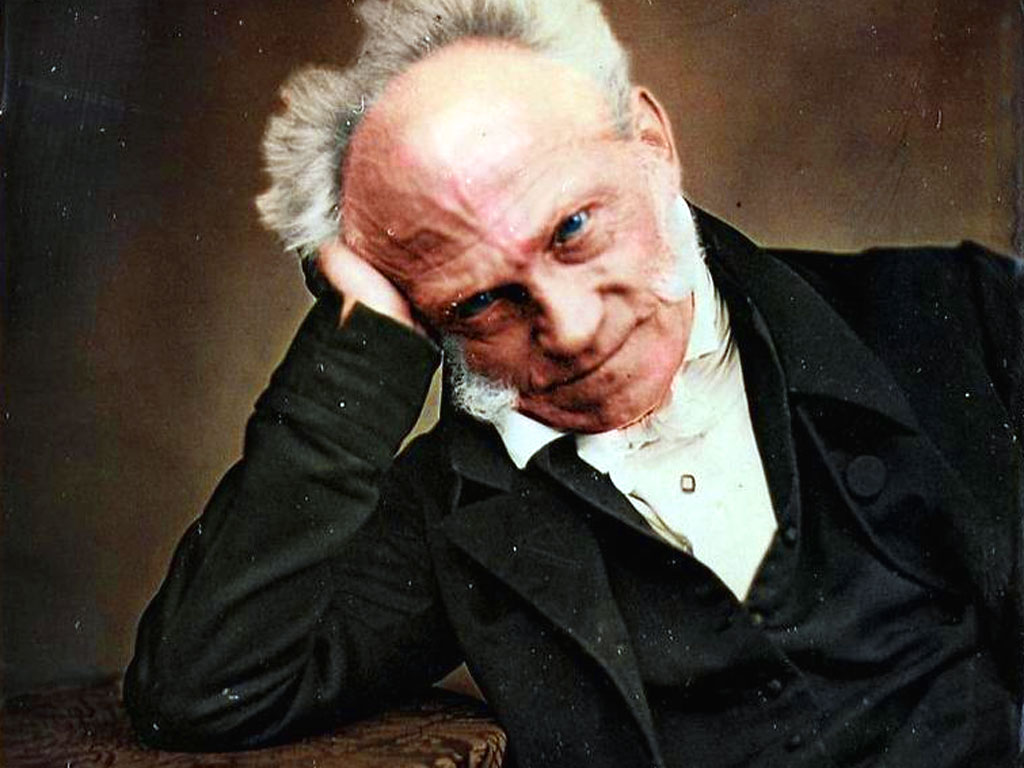

Edwin Edman is a sour-sweet friend of my philosophy, but was (before this last war) much offended at my Toryism which he felt to be Fascist. He appreciates some parts of my philosophy—the “spiritual” or religious radiations of it, but I am not sure that he respects the respect I have for matter or “Will” (according to Schopenhauer).

Ask him what he thinks of my “Idea of Christ.” My own opinion of it is that I was never more religious in insight and never less religious in opinion. The Catholics like and condemn it. Prof. Guzzo, of Turin and his wife have beautifully translated it into Italian; they think I am more truly Christian than any of the Fathers; but I hear that an American Catholic Bishop has said that not one sentence in that book could have been written by a Christian. I agree with both judgments, if by being a good “Christian” you understand being a disciple of Christology or worshipper of God in Man.

I don’t think I have moved, ever, either to the Right or to the Left. I have radiated, and now feel more at home than in my callow youth in both camps: but I don’t agree at all with the Left about the Right or with the Right about the Left. It is only where they love that they are intelligent, both of them, in regard to what is good in their object; neither sound, however, about the cosmological importance of their interests.

Yours sincerely

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: Alderman Library, University of Virginia at Charlottesville.