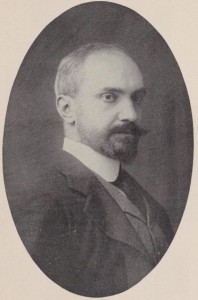

To Mr. Helder

To Mr. Helder

Paris. May 28, 1906

Dear Mr Helder,

Your question about “Strong defenses” for individual immortality puzzles me a good deal—I can think of none. As to my personal opinion on the subject, you will find it expressed at length in the last two chapters of volume III of my book on “The Life of Reason”—the volume (which can be got separately) on “Reason in Religion”. But you will get little comfort out of it.

Yours truly,

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Alderman Library, University of Virginia at Charlottesville

To Daniel MacGhie Cory

To Daniel MacGhie Cory To Benjamin Apthorp Gould Fuller

To Benjamin Apthorp Gould Fuller

To Allison Delarue

To Allison Delarue