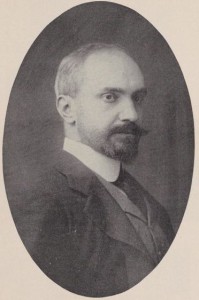

To Susan Sturgis de Sastre

To Susan Sturgis de Sastre

22 Beaumont St.

Oxford, England. October 10, 1917

Some time has passed since I have written to you or Josephine and you may like to hear that I am sin novedad. My lodgings here and the routine of my life in Oxford suit me pretty well, and when I go away it is always to return with a sense of relief and freedom. Of course, it is well for me to have a little change occasionally, and see people. I went some time ago to Bath to meet my old friend Moncure Robinson, who is now a confirmed old bachelor of forty-two with luxurious habits. He took me in his motorcar to London where he has a house, and I spent one night there before going on to Lord Russell’s, whose wife No 3 has now come back to him, so that she is as good as if she were No 4. They were having a middle-aged second honey-moon.embarrassing and not very agreeable sight for the by-stander. The lady, however, is very nice to me, pretends to read my books, etc. I made attempts some time ago to send you one of her novels, but I suppose the censor intercepted it. I ought to have had it sent by the publisher; in that case they let books through, I believe, but I am not sure that you would really be amused by her not very amiable recollections of her life in Germany.

In London I have seen Elsie Beal and her very plain daughter Betty, who is eighteen. They came with the idea of spending the winter in England, as Boylston is at the American embassy here: but Elsie is not amusing herself, and they are going back. Elsie is rather a wreck, looks like a Wigglesworth, and isn’t clever or kind enough to make up for her lost looks and manners, which last were never natural. The daughter is unaffected and robust, but deplorably ugly, except for a nice complexion.

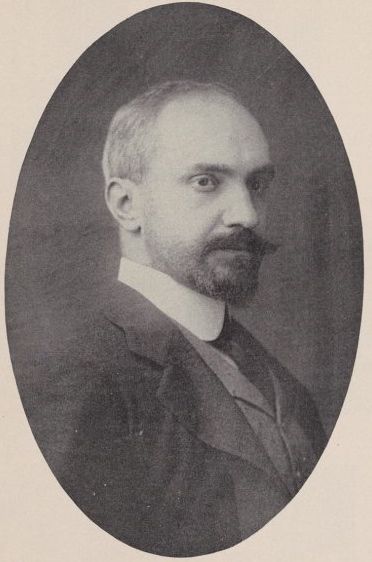

My chief preoccupation now is a book to which Strong and I are contributing: it is to be published in America, and there is a lot of sending manuscript and comments—we are trying to agree, at least in our vocabulary—to and fro, which often involves delays due to the necessity of getting permits from the censor, and the slowness of communications. We haven’t yet lost anything at sea, however, which I suppose is rather good luck under the circumstances. Strong writes from Switzerland: “Margaret has been in Zurich for a month, riding, going to the opera, & dancing the tango (with an Argentinian dancing-master named Fernandez!!!). She comes back on Sunday to lead a sober and I hope literary life at this institution. I am flourishing generally but disabled still as to my feet—half dead from the knees down. But the future is not unhopeful”.

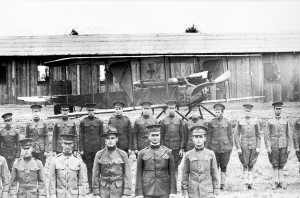

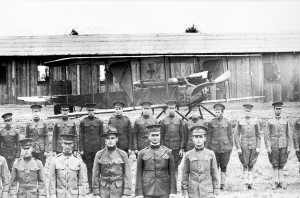

Oxford, which has been full of cadets for a year, now has a new species—the American Aviation Corps, with their strange appearance—yet so familiar to me that I sometimes fancy I am at Harvard going to a foot ball game. One has brought a letter to me, but I found him rather dreadful..—I receive the Lectura Dominical regularly (on Saturdays). Love to all from Jorge Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Two, 1910-1920. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Alderman Library, University of Virginia at Charlottesville

To Daniel MacGhie Cory

To Daniel MacGhie Cory