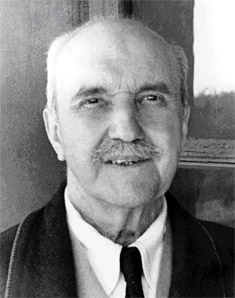

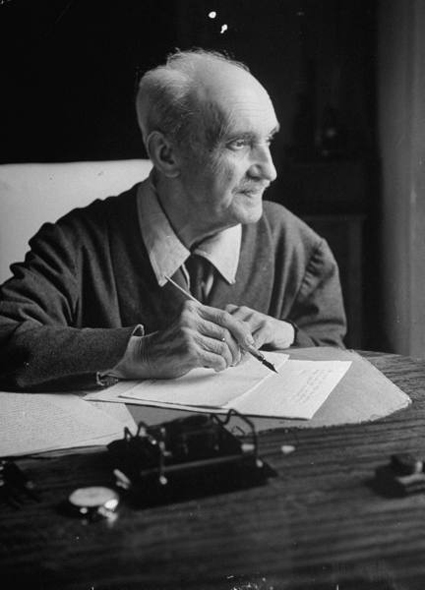

To Henry Ward Abbot

To Henry Ward Abbot

Schiffbauerdamm 3II

Berlin, Germany. October 6, 1886

Dear Abbot.

I said, I believe, in my last letter that I would write before long again, because I had more to say in answer to all you told me than I could put into one letter. I have put off writing all this time partly because I thought I might possibly hear from you, and partly because I was afraid of making myself a nuisance. But I have felt like writing to you very many times. You asked why I take an interest in you, which after all it is natural I should take; but since that time I have been forced to wonder myself why I take so much interest in you. And as far as I can see the reason is this. I suspect you are going through a critical period, and I feel that you are dissatisfied with yourself. Why are you dissatisfied with yourself? Another man, I for instance, would be satisfied to be as you are. You are not dissatisfied with yourself because you can’t do what other people do and what is expected of a man, but because you imagine you can’t do something very excellent which you feel somehow drawn to do. Now I am interested in seeing if you are going to attempt this something excellent, or not; whether you are going to prefer to live on moodily, taking refuge more or less in dissipation, or whether you are going to start out in some direction where you see something you really value. It isn’t at all a question of what you can accomplish; it is only a question of what attitude you are going to take, what sort of things you are going attend to. Now you know that I am as willing that people should worship the devil as that they should worship God; I only ask in whose service will they live more smoothly, gracefully, and intelligently. It’s all prejudice and point of view to say that one sort of life is better than another, because it pursues different objects. All that an emancipated man asks is which objects attract him most, and what are the means of attaining those objects. To do right is to know what you want. Now when you are dissatisfied with yourself, it’s because you are after something you don’t want. What objects are you proposing to yourself? are they the objects you really value? If they are not, you are cheating yourself. I don’t mean that if you chose to pursue the objects you most value, you would attain them; of course not. Your experience will tell you that. Therefore a wise man won’t value anything much. But this wise indifference, this safeguard against disappointment, would come too soon if it came before a man had started in the direction of his true satisfactions. Indifference is quite premature if it leads a man to misunderstand his own desires. In the first place there is always some small chance of success; but success in getting after much labor what you really don’t care for is the bitterest and most ridiculous failure. And in the second place, to have before one admired objects, and hopes of true satisfaction, is itself a very pleasant and ennobling thing. So if, as I suspect, you are wavering a little in regard to the direction you will start out in, I hope you will think this over; because, as I am not a moralist, nor a minister, nor an old man, nor anyone with a right to preach and give advice, I may possibly have struck the truth. I trust you will not be offended at my writing to you as I do. Gossip and jokes have I not, but that which I have I give you; don’t doubt that I am “with the greatest respect” your sincere friend

George Santayana

P.S. When you see Ward, please give him an affectionate scolding from me.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Butler Library, Columbia University, New York NY.