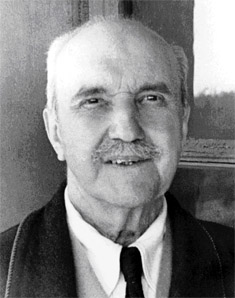

To Richard Colton Lyon

To Richard Colton Lyon

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. June 18, 1950

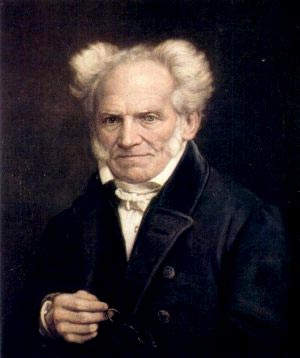

I have never been a great reader of Milton and I may misjudge him: but I suspect that if I had read him more I should like him less, so that it is as well to give you only my superficial impressions. I don’t at all agree with Ezra Pound in hating him. I used to know Lycidas by heart and to delight in saying it over-E. P. might say that this explains how bad my verses were, for that was just the misguided period of my life when I wrote them. But in Paradise Lost it is not the absence of a philosophy but the evident sub-presence of a sort of mummified Old Testament philosophy that fills his sails. I admit that he is sublime in his poses: but it is the sublimity of terror not of joy. And he doesn’t understand at all the position of a real angel rebelling against a monarchical God. It would be the position of Berkeley rebelling against matter. He would not choose evil rather than good. That is only the nursery-maid’s “naughty” and “nice”. He would be choosing the immediate, the obvious, the inescapable, the Schopenhauerian “the world is my idea”, for faith of any sort which is only an impulse to bet, to jump in the dark. I am very glad to see that at the end of your essay you suggest the question what Milton understood by “the good”. He understood by it what the Calvinistic catechism calls good: the nursery-maid’s “nice” translated into the cry of superstitious escape from terror. “Duty” also needs to be analysed etymologically. It means what is owed, what you are bound by contract to perform.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.