To Monica Waterhouse Bridges

To Monica Waterhouse Bridges

C/o Brown Shipley & Co. 123, Pall Mall, S.W.

Rome. April 26, 1930

Dear Mrs Bridges,

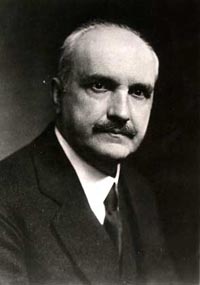

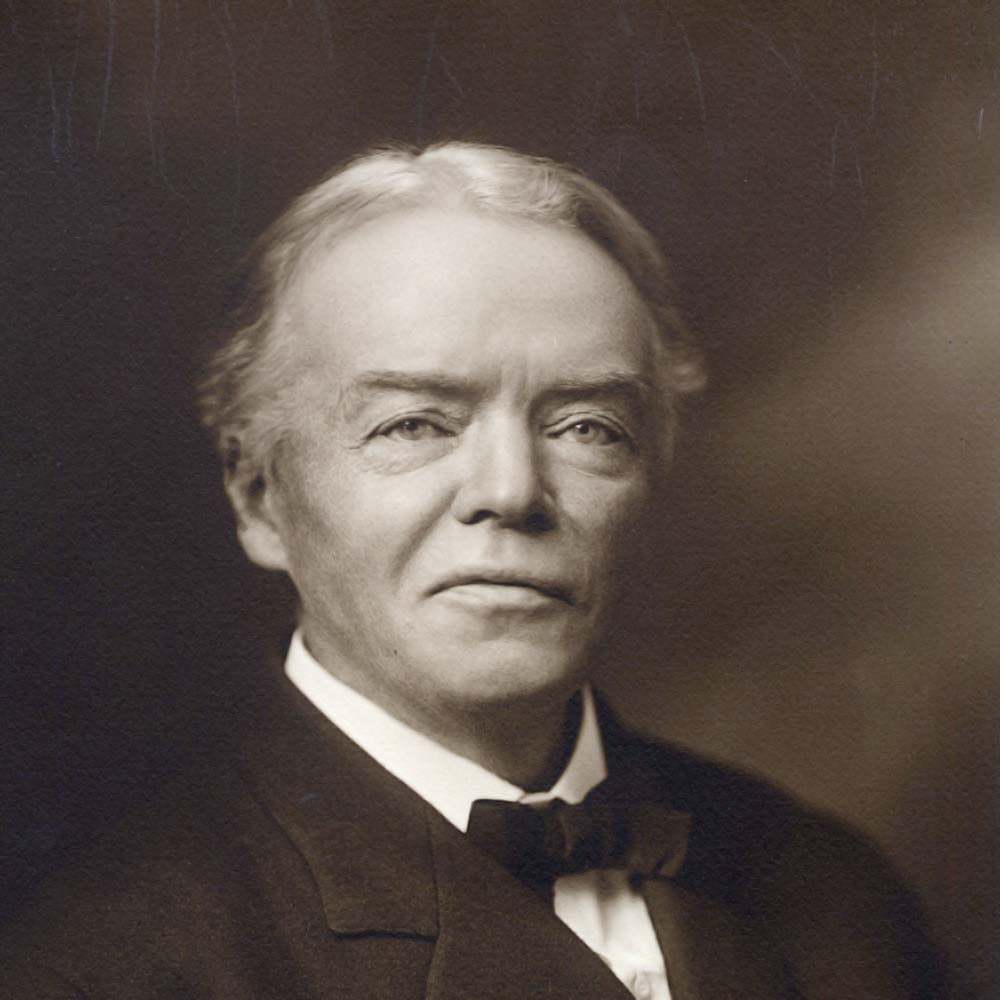

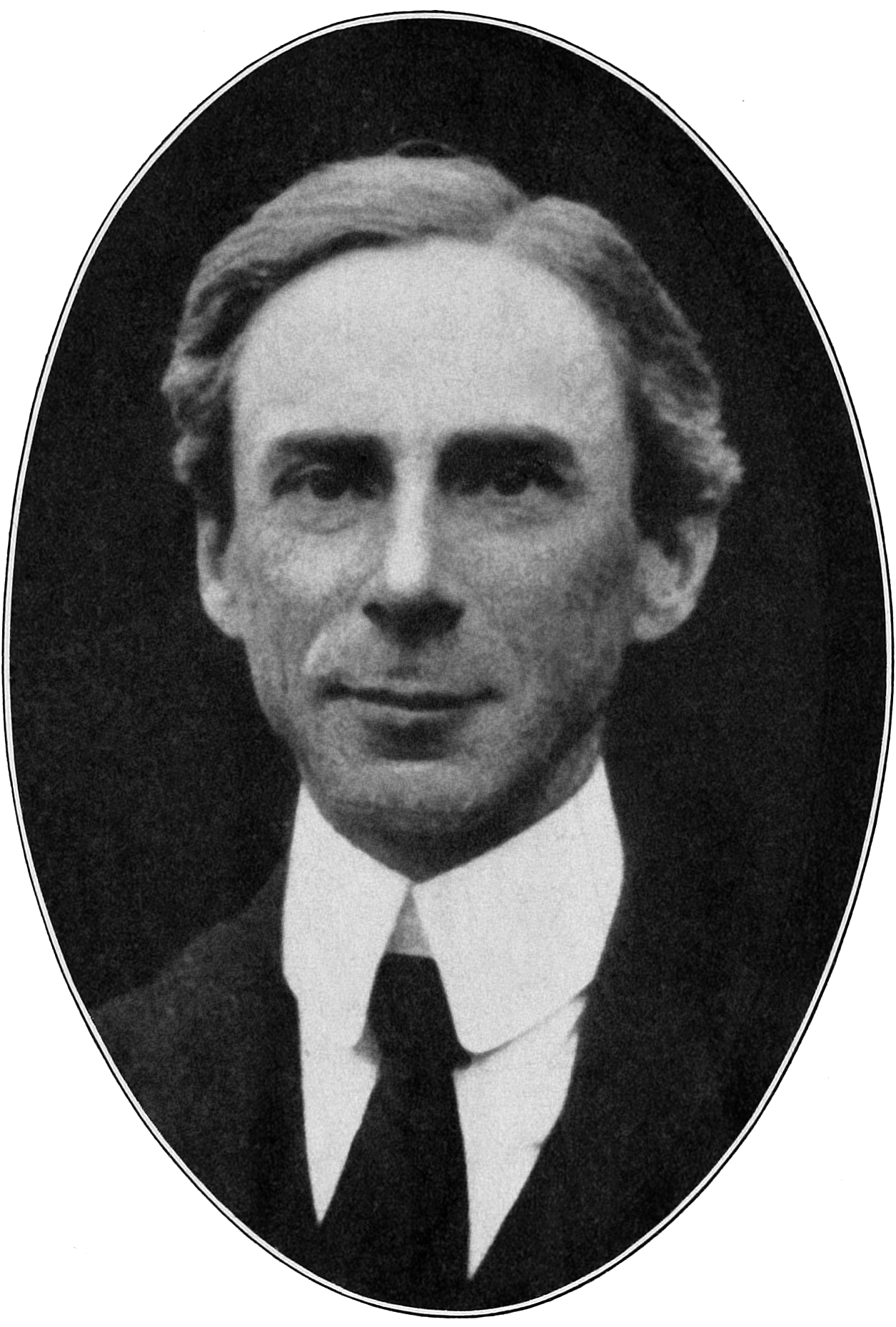

Let me add my word of sympathy to the many that must be coming to you from every quarter. This inevitable separation can hardly help leaving all the greater void in your life, in that happily it has been put off for so many years. But you have many satisfactions to balance against this sadness, and not the least, which is a satisfaction to all of us also, is that Mr Bridges should have crowned his last years with such a magnificent performance as his Testament of Beauty. I don’t know what judgement posterity may pass—or may drift into—in regard to this poem, and to the rest of your husband’s work, but in any case it is a noble portrait of his mind, so sensitive, brave, open, and healthy; and it must remain a monument to the sentiment of cultivated English people in his time, and in this modern predicament of the human spirit. You doubtless saw a long letter which I wrote to him about it, dwelling (at his request) on the doctrinal side of it, in so far as I could make it out; but that letter didn’t do justice to what I think is the chief merit of the work—its deep sense of citizenship in nature, and its courage and good humour at a moment when the future seems so dubious for England and for the world.

You know better than anyone—for I suspect you had a hand in it—that I owe Mr Bridges a particular debt for his generous recognition of my early writings, when they were quite unknown in England and not much respected in America. His kindness and friendship went even further, and I think he would have liked to domesticate me in England altogether. I too would have liked nothing better when I was a young man; but at the time when the thing might have been possible—during the war and after— it was too late. Neither my health nor my spirits were then fit for beginning life afresh, as it were, in a new circle. The best I could do then was to retire into a mild solitude, and complete as far as possible the writing that I had planned. It is now more than half done.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Four, 1928–1932. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: The Bodleian Library, Oxford University, England.