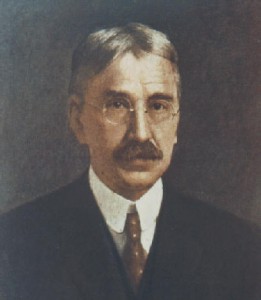

To Horace Meyer Kallen

To Horace Meyer Kallen

C/o Brown Shipley & Co. 123 Pall Mall, London, S.W.

Rome. March 23, 1927

Normal religious experience is the assurance that one is living in a world the economy of which is authoritatively known, so that conduct, sentiment, and expectation have a settled basis. If we distinguish . . . between the true and the illusory parts of such a religion, the illusory part, when it is worth considering at all, seems to me to be poetry: that is, it is an imaginative fiction, rich in emotions, which serves nevertheless to adjust mankind to its fate, and to lend form to it’s relations to things, such as worldly life and eternal truth, which are not easily expressed in commonsense language.

There is a great obscurity, to my sense, in your philosophical first principles. Are you a mere humanist, without any physics? Why then don’t you consider the Catholic church, for instance, as just as respectable and acceptable a view of the world and as good a method of human life, as that of the contemporary Intelligentsia? Certainly the church has the advantage humanly: it is richer in fruits of every description, much riper and of sweeter flavour.

I can’t help feeling that your tartly external and perpetually insulting attitude to this church is founded on your love of truth: you hate her for her very excellences, because you are convinced that they are deceptive. I agree with you there; but then the very naturalism on which that agreement is based, if you steadily accepted it (as Spinoza did, for instance) might lead you to regard those deceptive charms historically with more sympathy and understanding: because the natural predicaments of man and his history made them inevitable and dramatically right.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Three, 1921–1927. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

Location of manuscript: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York NY.

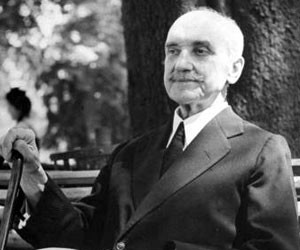

To Winifred M. Bronson

To Winifred M. Bronson