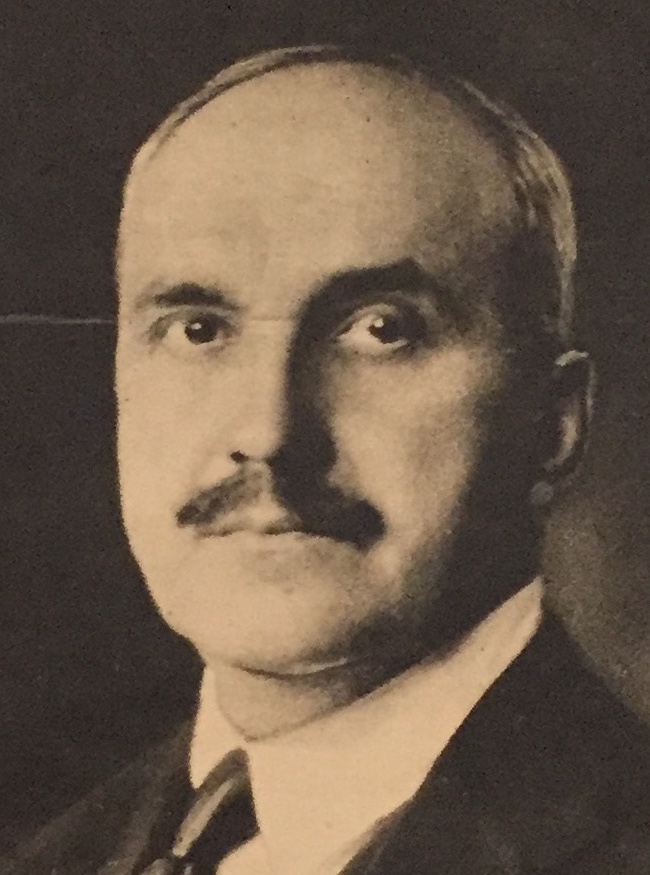

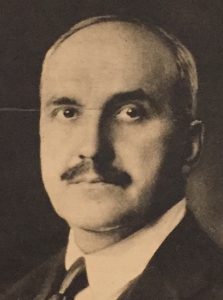

To Corliss Lamont

To Corliss Lamont

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. January 6, 1950

Without bothering you with technical arguments, let me suggest this natural status of immaterial forms and systems of relations in the case of music. Music accompanies savage life as well as that of some birds, being a spontaneous exercise of motions producing aerial but exciting sounds, with the art of making them, which is one of the useless but beloved effusions of vital energy in animals. And from the beginning this liberal accompaniment adds harmony and goodwill to dancing and war; and gradually it becomes in itself an object of attention, as in popular or love songs. In religion it also peeps out, although here it ordinarily remains a subservient element, inducing a mood and a means of unifying a crowd in feeling or action, rather than a separate art. Yet it is precisely as a separate art, not as an accompaniment to anything practical, that music is at its best, purest and most elaborate. And certainly the sensibility and gift of music is a human possession, although not descriptive of any other natural thing.

Apply this analogy to mathematics, logic, aesthetics, and religion, and you have the naturalistic status of ideal things in my philosophy. “Humanism” has this moral defect in my opinion that it seems to make all mankind an authority and a compulsory object of affection for every individual. I see no reason for that. The limits of the society that we find congenial and desirable is determined by our own condition, not by the extent of it in the world. This is doubtless the point in which I depart most from your view and from modern feeling generally. Democracy is very well when it is natural, not forced. But the natural virtue of each age, place, and person is what a good democracy would secure—not uniformity.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: Unknown.