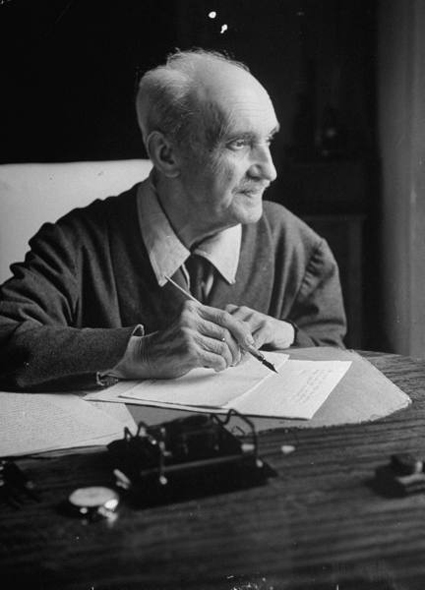

To Rosamond Thomas Bennett Sturgis

To Rosamond Thomas Bennett Sturgis

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6,

Rome. March 15, 1946

I wish we had a medical thermometre for style, so that I could take my literary temperature when I sit down to write, and be reassured when it indicated blood heat, or average rationality, and be warned off and take a rest or a glass of something strong if it indicated dangerous fever, involving bad language, or vitality lower than 36° threatening platitudes and imbecility. Yet in the absence of scientific diagnosis it is a resource to take some good coffee which will probably do good; or at least make foolishness unconscious.

I didn’t skip a single page of the Harvard book, remembering that you believe firmly in education and not, like me, in inspiration or drink—and I wanted to inform myself a little on that important subject. Frankly, I thought it a dull book, and full of needless repetition; but at least I was relieved to find that “general” education did not mean education in general (Kindergardens being excluded) but meant what I should call essential education, or learning the things that are most worth knowing, not for their utility in making a living, but in giving us something to reward us for being alive.

There is an orthodox system of life and thought, called apparently “democracy” which must be made the basis and criterion of right education and right character. This is new to me in America. In my time Harvard wasn’t at all inspired in that way. Not that anyone was hostile to democracy, but that we thought enlightenment lay in seeing it, and all other things, in the light of their universal relations, so as to understand them truly, and then on the basis of the widest possible knowledge, to make the best of the facts and opportunities immediately around us. But now education is to be inspired by revealed knowledge of the vocation of man, and faith in our own apostolic mission. Perhaps the war has made this view more prevalent than it would have been in uninterrupted peace.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Seven, 1941-1947. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.

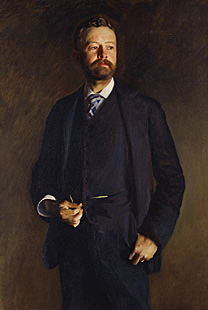

To George Sturgis

To George Sturgis