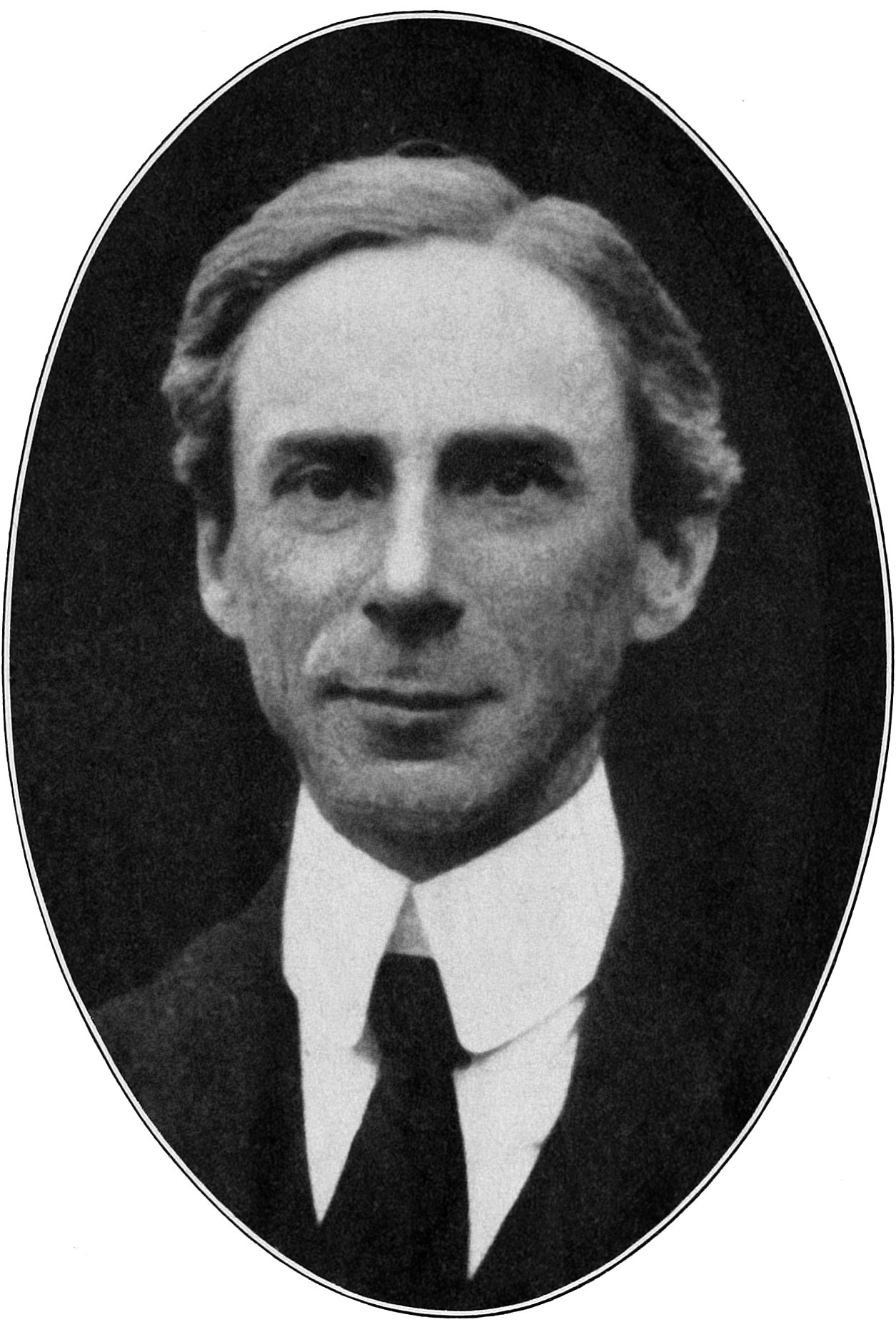

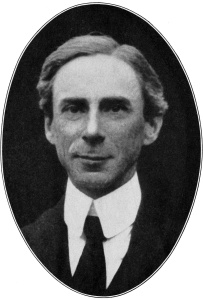

To Bertrand Arthur William Russell

To Bertrand Arthur William Russell

Queen’s Acre

Windsor, England. February 8, 1912

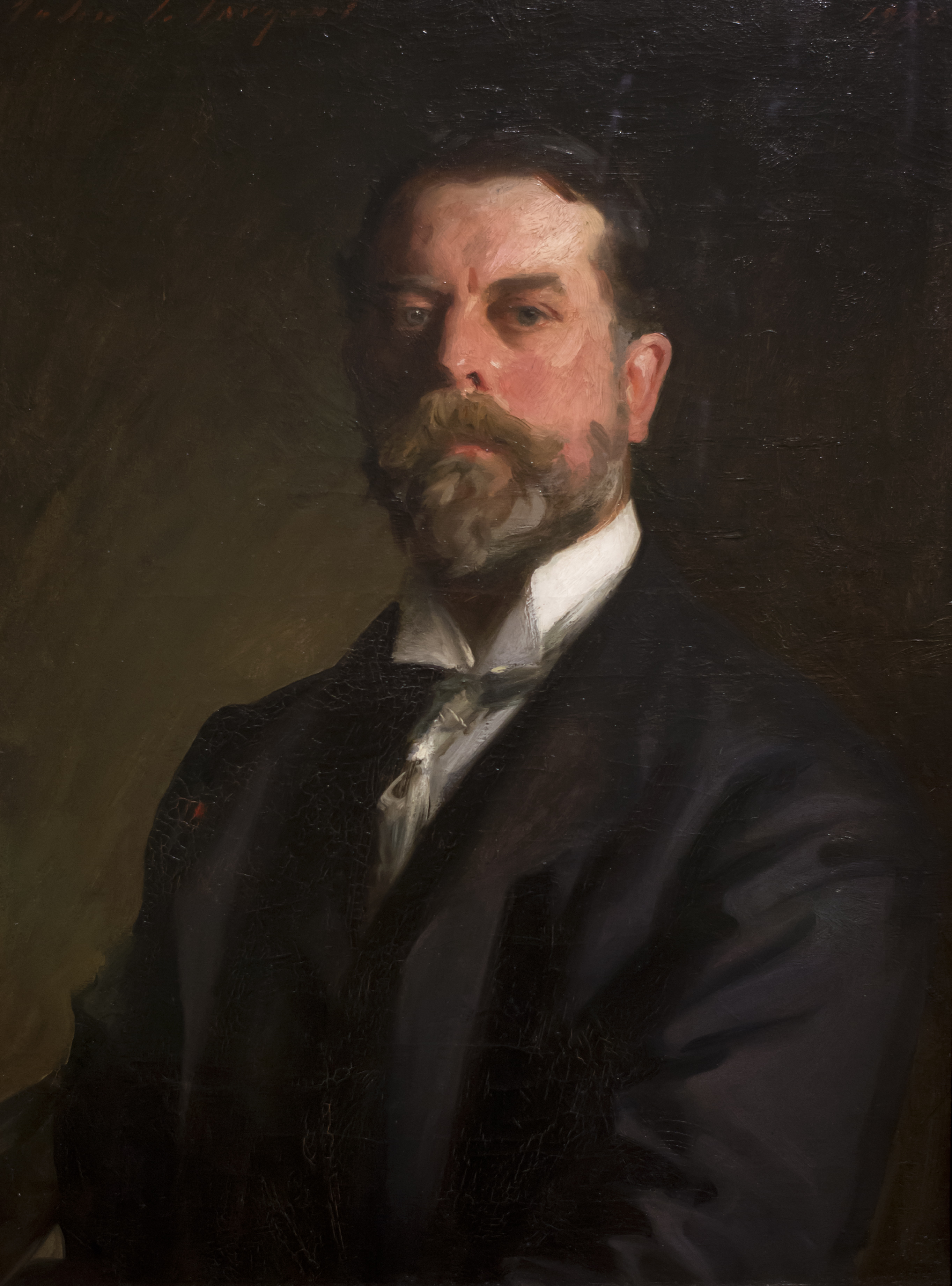

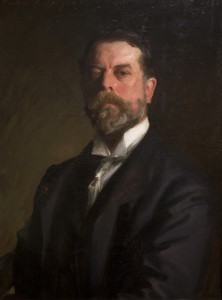

I have a proposal to make, or rather to renew, to you on behalf of Harvard College. Would it be possible for you to go there next year, from October 1912 to June 1913, in the capacity of professor of philosophy? . . . What they have in mind is that you should give a course—three hours a week, of which one may be delegated to the assistant which would be provided for you, to read papers, etc.—in logic, and what we call a “seminary” or “seminar” in anything you liked. It would also be possible for you to give some more popular lectures if you liked, either at Harvard, or at the Lowell Institute in Boston. For the latter there are separate fees, and the salary of a professor is usually $4000 (£800). We hope you will consider this proposal favourably, as there is no one whom the younger school of philosophers in America are more eager to learn of than of you. You would bring new standards of precision and independence of thought which would open their eyes, and probably have the greatest influence on the rising generation of professional philosophers in that country.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Two, 1910-1920. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Mills Memorial Library, Bertrand Russell Archives, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada