To Sylvia Hortense Bliss

To Sylvia Hortense Bliss

C/o Brown Shipley & Co.

123, Pall Mall, London

Rome. January 19, 1935

My dear Miss Bliss,

I should have thanked you sooner for “Sea Level” if I hadn’t followed your injunction to read it by bits; after which I have reread it more or less as a whole, in search of your philosophy. You must have felt that I should sympathize with this, else you wouldn’t have thought of sending me the book. Your perfect freedom from religious or mock-religious presumptions—and also from hostility to religion—your clear view of truth, and your sound naturalism do appeal to me very much. I have always felt, what you express in regard to trees especially, that our relation to the rest of nature is fraternal, and that the possession of consciousness or (if we possess it) of reason doesn’t justify us in regarding plants, animals, or stars as unreal, or as made for our express benefit. And the sea, though you speak little of it, has always been a great object lesson to me, a monitor of the fundamental flux, of the loom of nature not being on the human scale. So far, if I don’t misrepresent you, we agree. But I am ill conditioned to appreciate your knowledge and love of flowers and of the countryside generally; and I have been so immersed all my life in religious speculation, in literature, in history, and in travel; I have lived so exclusively in towns and universities, and amid political revolutions and wars, that your simple idyllic world, and your intense individualism, leave me rather with a sense of emptiness. And haven’t you that sensation yourself? I don’t know what trials you may have had to endure or what misfortunes; your individualism is wholly philosophical, it touches the Ego in its transcendental capacity, and you tell us nothing of your own person; but your tone in speaking of death, of cities, and of the mediation of other minds between you and nature, seems to me overcharged with distaste and melancholy. Aren’t men also a part of nature? And if we could really penetrate into the life of matter, shouldn’t we find it everywhere essentially as wasteful, groping, and self-tormented as is the life of mankind? And on this fundamental irrationality, human society builds so many charming things—music, for one, which you appreciate—but also material and moral splendours of every description. The refraction of truth in human philosophies, for instance, is no mere scandal: it composes a work of human art, and partakes of the force both of truth and of imagination. It seems to me a pity, therefore, to leave it out of one’s field of interest.

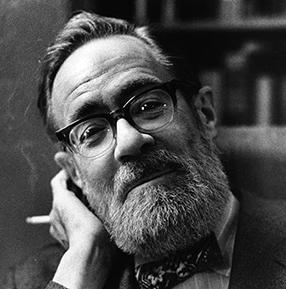

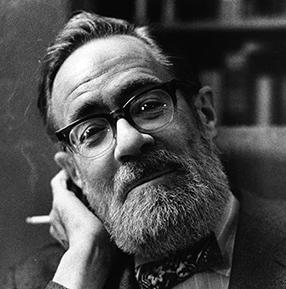

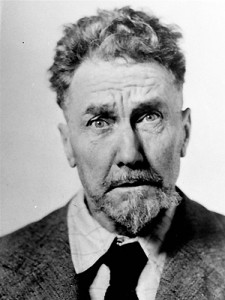

Let me add that I appreciate the level dignity of your style and diction. You are doubtless aware that you often lapse into blank verse, and that, if you chose, you could print your book in that form with very little alteration. You have preferred a more modern arrangement, doubtless for good reasons; but you will deceive nobody into mistaking you for a real modern, like Mr. Ezra Pound, for instance, whose Quia Pauper Amavi I had been reading immediately before receiving your book. But though your restrained voice may not attract attention so scandalously, I am sure that you will give more pleasure to those who do hear you, and will be more gratefully remembered.

Yours sincerely,

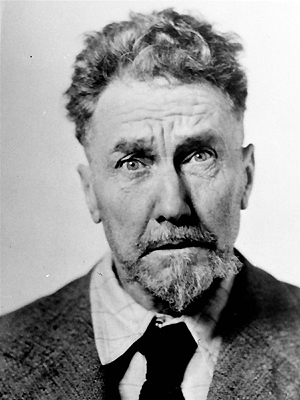

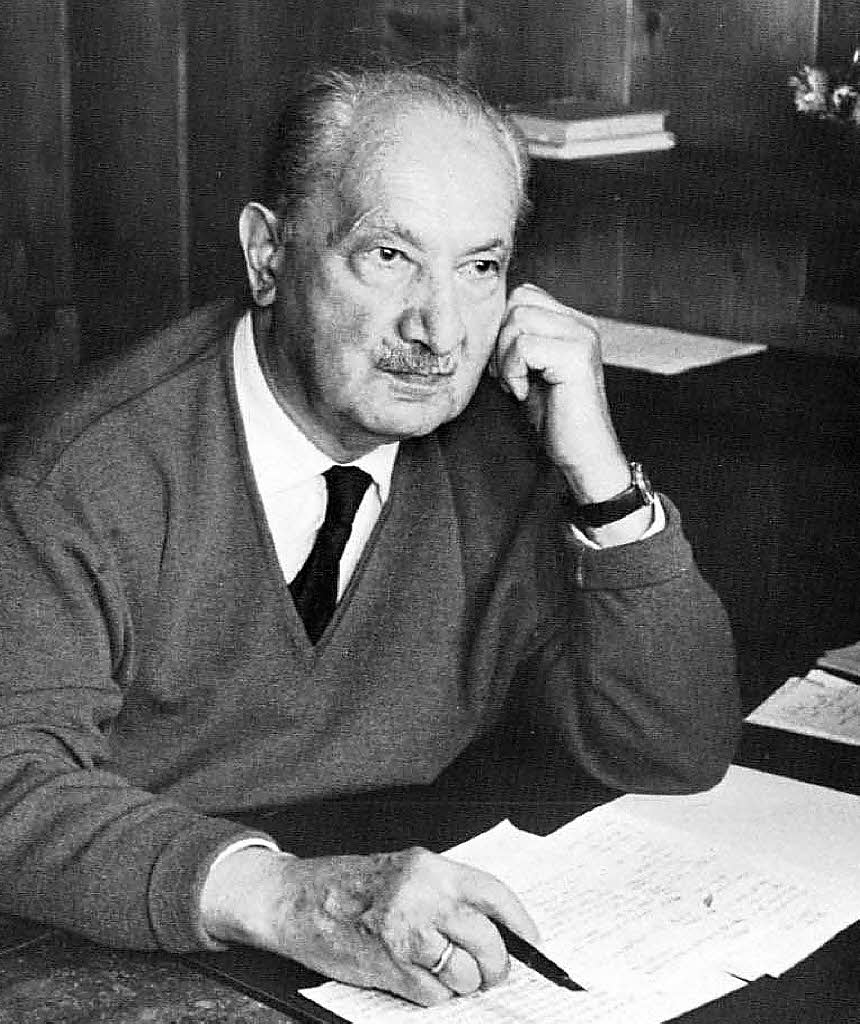

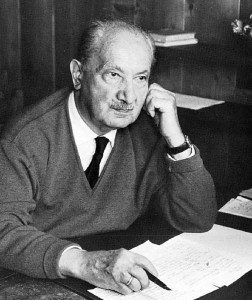

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Five, 1933-1936. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.