Coming to America

Academic dress, or regalia, is a type of clothing worn by students and faculty. In the United States, this form of dress generally consists of a cap and gown and is worn during commencement ceremonies or other special occasions. The history of academic regalia dates back to the Middle Ages as the first universities as we know them were established in Europe. During this period, academic dress was not merely ceremonial; rather it was worn as a daily uniform by students and instructors alike. The style of dress, a long hooded robe, was derived from the garb worn by medieval clerics (Figure 1).[1]

![Figure 1. This illustration from the Grandes Chroniques de France, shows a group of students and their instructor wearing robes during a philosophy lesson in the late 14th century. [Image credit: Wikipedia]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/14th-Century.jpg)

Figure 1. This illustration from the Grandes Chroniques de France, shows a group of students and their instructor wearing robes during a philosophy lesson in the late 14th century. [Image credit: Wikipedia]

Long before today’s students were forced to contend with classrooms pumped full of freezing air, their studious predecessors used the long robes to keep warm in Europe’s chilly university halls. Jumping ahead a few centuries, the traditions of academic regalia, particularly those derived from Oxford and Cambridge, found a firm foothold amongst the first American universities including Harvard, Princeton, and Columbia (Figure 2).

![Figure 2: Sixteen-year-old Princeton University student, James McCulloch, in his undergraduate robes. Painted some time prior to 1773, when Princeton was still known as the College of New Jersey. [Image credit: Wikipedia]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Princeton-234x300.jpg)

Figure 2: Sixteen-year-old Princeton University student, James McCulloch, in his undergraduate robes. Painted some time prior to 1773, when Princeton was still known as the College of New Jersey. [Image credit: Wikipedia]

During the eighteenth century, students, and some faculty, at these institutions regularly wore academic gowns on campus.

[2]

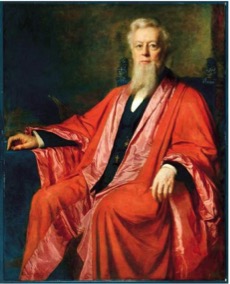

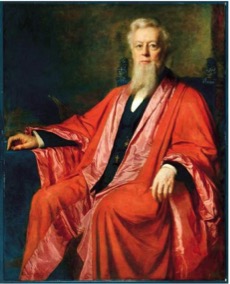

It was not until the mid-nineteenth century, however, that the role of academic regalia in American universities came to resemble its modern function as solely ceremonial attire. At this time, there was little standardization of academic dress between the different colleges and universities in the United States (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard, former president of Columbia University, in academic robes. This portrait, by Eastman Johnson, was completed in 1886 before there was any formal standardization of academic dress. [Image credit: Transactions of the Burgon Society]

In 1895 the Intercollegiate Commission held a meeting at Columbia University attended by representatives from some of the top scholastic institutions to discuss adopting a regulated code of academic dress. Gardner Cotrell Leonard, whose family operated the manufacturing firm Cotrell and Leonard in Albany, New York, was also present at the discussion to provide practical advice

[3] as he had, several years earlier, designed the gowns for his class at Williams College and had (in 1893) published an article on dress standardization that became a significant factor contributing to the creation of the Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume (passed in March 1895 by representatives from Princeton, Columbia, New York, and Yale).

[4]

Which Robe is Which?

The Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume has been amended five times since its inception (in 1932, 1957, 1959, 1973, and 1987).[5] While there are many variations in gown, sleeve, and hood styles (not to mention the effects of school colors), there are some basic guidelines for recognizing degrees based on gown design. In general, bachelor’s and master’s gowns are untrimmed and may both feature hoods; the master’s gown typically has oblong sleeves and a longer hood than the bachelor’s (Figure 4).

![Figure 4. An image depicting the difference in length between a bachelor’s and master’s hood. [Image credit: The Cap and Gown in America: Reprinted from the University Magazine for December, 1893]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Backs.jpg)

Figure 4. An image depicting the difference in length between a bachelor’s and master’s hood. [Image credit: The Cap and Gown in America: Reprinted from the University Magazine for December, 1893]

The doctoral gown is the easiest to distinguish as it is trimmed in velvet down the front of the robe and has three velvet bars on the bell-shaped sleeves; the doctor’s gown also has the longest hood of the three styles (Figure 5).

![Figure 5. William Lyon Mackenzie King, former Prime Minister of Canada, in his doctoral gown from Harvard University (c. 1919). [Image credit: Wikipedia]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/King5.-215x300.jpg)

Figure 5. William Lyon Mackenzie King, former Prime Minister of Canada, in his doctoral gown from Harvard University (c. 1919). [Image credit: Wikipedia]

Although the Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume describes the design of academic regalia, no body exists to enforce adherence to the code. As a result, the Code of Academic Costume may be adapted by any university provided that the changes are “reasonable and faithful to the spirit of the traditions which give rise to the code.”

[6] Therefore, the Code of Academic Costume is less of a rulebook than it is a general guideline led by tradition.

The Santayana Edition’s Hidden Treasure

Tucked away amongst the books and manuscripts of the Santayana Edition is a treasure of academic dress history: George Santayana’s doctoral gown from Cotrell and Leonard. That this gown is a doctoral robe is clear from its design; the black gown features black velvet facing down its front as well as the distinctive bars on the sleeves also done in black velvet (Figures 6-8).

![Figure 6. The front and back of George Santayana’s doctoral gown. This gown is very similar to the one shown in Figure 5 apart from the crow’s feet on the lapels of King’s robe. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gowns6-225x300.jpg)

Figure 6. The front and back of George Santayana’s doctoral gown. This gown is very similar to the one shown in Figure 5 apart from the crow’s feet on the lapels of King’s robe. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]

![Figure 7. A closer look at the gown’s sleeve. Note the velvet stripes and the wide bell shape, both characteristic of a doctoral gown. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gowns7-300x226.jpg)

Figure 7. A closer look at the gown’s sleeve. Note the velvet stripes and the wide bell shape, both characteristic of a doctoral gown. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]

![Close-up of the pleats and braided details on the back of the gown. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gowns8-300x225.jpg)

Figure 8. Close-up of the pleats and braided details on the back of the gown. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]

The gown is in good condition for its age and still clearly bears the brand label on its interior (Figure 9).

![Figure 9. Cotrell & Leonard label on the interior of Santayana’s gown; notice the faded initials “G.S.” above the brand name. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gowns9-300x226.jpg)

Figure 9. Cotrell & Leonard label on the interior of Santayana’s gown; notice the faded initials “G.S.” above the brand name. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]

The exact date on which Santayana purchased his gown is unknown. However, since he earned his doctorate from Harvard in 1889, one may infer that he acquired his gown sometime around this year. Following his graduation, Santayana taught at Harvard until 1912, at which time he retired and moved to Europe. Before leaving the country, in a letter dated December 12, 1911, Santayana wrote to one of his former students at Harvard, Horace Kallen:

In looking over my goods and chattels, I find a doctor’s cap and gown which I don’t know what to do with. If you haven’t one and would like it, I should be very glad to have you take it off my hands.[7]

In another letter written on December 29th, Santayana notes that he has sent off his academic regalia to Kallen.[8] Many years later, the gown arrived at the Edition as a donation from Kallen’s widow. Its corresponding cap remains with Kallen’s son, David.

Although academic regalia has undergone many changes in the United States, it remains grounded in European traditions that span centuries of scholastic history. We at the Santayana Edition feel fortunate to have this artifact of early American academic dress in our possession and we are excited to share a piece of George Santayana’s past with our colleagues.

[1] Eugene Sullivan, “Historical Overview of the Academic Costume Code,” American Council on Education, accessed February 4, 2016, http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/Historical-Overview-Academic-Costume-Code.aspx.

[2] Stephen L. Wolgast, “Timeline of Developments in Academic Dress in North America,” Transactions of the Burgon Society 9, (2009).

[3] Stephen L. Wolgast, “The Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume: An Introduction,” Transactions of the Burgon Society 9, (2009), 13.

[4] For Leonard’s article see Gardner Cotrell Leonard, The Cap and Gown in America: Reprinted from the University Magazine for December, 1893 (Albany, NY: Cotrell & Leonard, 1896).

[5] For detailed descriptions of the changes see Wolgast, pp. 23-32.

[6] Eugene Sullivan, “Academic Costume Code,” American Council on Education, accessed February 8, 2016, http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/Academic-Costume-Code.aspx.

[7] Holzberger, William G. and Herman J. Saatkamp Jr. eds., The Letters of George Santayana, Book 2: 1910-1920 (MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2002): 64-65.

[8] Ibid., 65.

Kristin Lee is a graduate student in Public History and an intern with the Santayana Edition.

![Figure 1. This illustration from the Grandes Chroniques de France, shows a group of students and their instructor wearing robes during a philosophy lesson in the late 14th century. [Image credit: Wikipedia]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/14th-Century.jpg)

![Figure 2: Sixteen-year-old Princeton University student, James McCulloch, in his undergraduate robes. Painted some time prior to 1773, when Princeton was still known as the College of New Jersey. [Image credit: Wikipedia]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Princeton-234x300.jpg)

![Figure 4. An image depicting the difference in length between a bachelor’s and master’s hood. [Image credit: The Cap and Gown in America: Reprinted from the University Magazine for December, 1893]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Backs.jpg)

![Figure 5. William Lyon Mackenzie King, former Prime Minister of Canada, in his doctoral gown from Harvard University (c. 1919). [Image credit: Wikipedia]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/King5.-215x300.jpg)

![Figure 6. The front and back of George Santayana’s doctoral gown. This gown is very similar to the one shown in Figure 5 apart from the crow’s feet on the lapels of King’s robe. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gowns6-225x300.jpg)

![Figure 7. A closer look at the gown’s sleeve. Note the velvet stripes and the wide bell shape, both characteristic of a doctoral gown. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gowns7-300x226.jpg)

![Close-up of the pleats and braided details on the back of the gown. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gowns8-300x225.jpg)

![Figure 9. Cotrell & Leonard label on the interior of Santayana’s gown; notice the faded initials “G.S.” above the brand name. [Image credit: Kristin Lee]](https://santayana.iupui.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Gowns9-300x226.jpg)