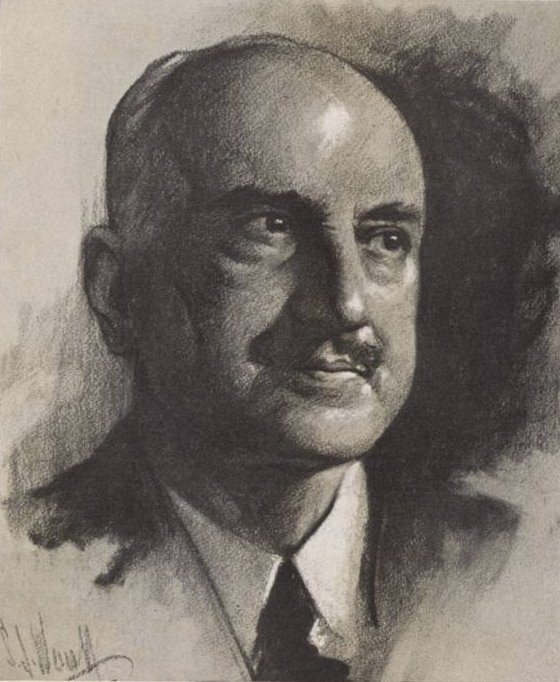

To Charles Augustus Strong

To Charles Augustus Strong

Rome. June 3, 1937

Dear Strong

Cory also wrote me that you had told him about the Fellowship, but without enlarging on his own feelings about it. He is not a Harvard man, and his philosophical friends in America–Edman and the rest–are at Columbia. His father, brother, and beloved aunt (a very important influence, I suspect) are New Yorkers. And academic shades, if such can be attributed to Harvard now, leave him indifferent. I can never get him to go, even for a day, to see Oxford or Cambridge. All this makes me think, a priori, that if his Fellowship involved residence at Harvard, he might not like it very much; and even if it does not involve residence, the Harvard authorities might expect some sort of co-operation or insertion (as Bergson would call it) of his work in theirs, something that Cory, with his independence, might not supply. I mention these circumstances, because I feel that perhaps the working out of your plan might encounter obstacles. It is not so clear a favour done to Cory as a direct legacy would be, although it may conceivably be better for him to have to meet these possible obstacles to the free enjoyment of the Fellowship.

I have been reading old American authors, and about them, Poe, Thoreau, Emerson. I find Emerson more definite than my memory painted him, also more human and almost light, but philosophically feeble. He is a fanatic faded white, but not really emancipated.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Six, 1937–1940. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004.

Location of manuscript: Rockefeller Archive Center, Sleepy Hollow NY.

To Boylston Adams Beal

To Boylston Adams Beal