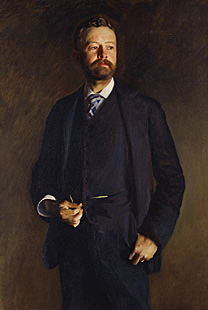

To Mary Williams Winslow

To Mary Williams Winslow

C/o Brown Shipley & Co. 123 Pall Mall, London, S.W.

Nice. March 19, 1923

As to politics, I watch what happens mainly with an eye to discerning, if possible, whether the great international socialistic revolution is coming or not. Russia and Italy now make me incline to believe that the cataclysm will not occur, and that things will go on very much as usual, with a change of personnel and of catch-words. Fascism is the most significant thing now: I wonder if in England the decent people will not eventually organize and arm against the politicians and restore the nation.

Much of what people complain of in the world after the war does not worry me; on the contrary, if only the “industrial situation” could remain always bad, and the population could diminish, especially in the manufacturing towns, I should think it a good thing. There are now too many people, too many things, and too many conferences and elections.

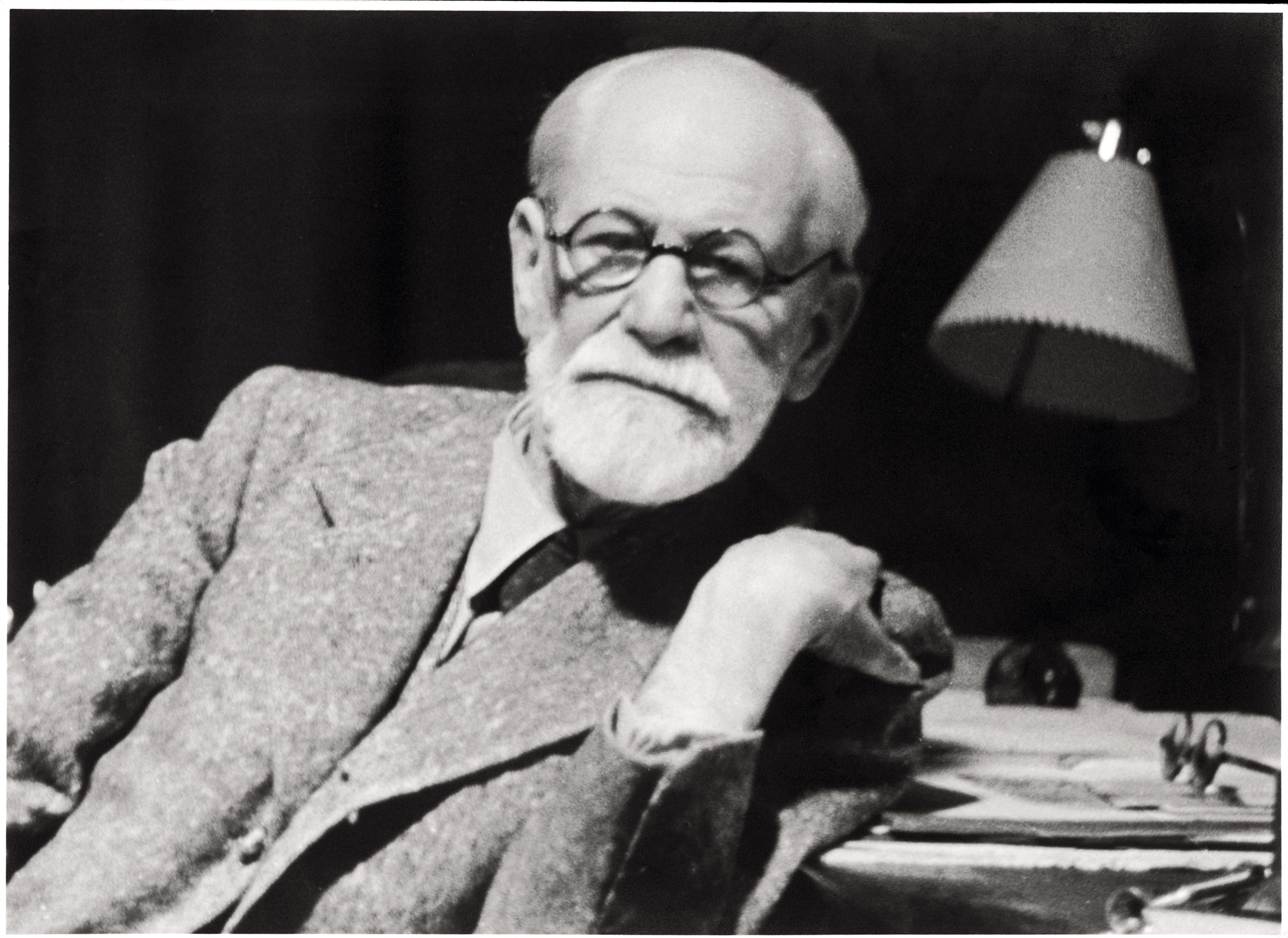

I have been reading a new book of Freud’s and other things by his disciples. They are settling down to a steadier pace, and reducing their paradoxes to very much what everybody has always known.

Einstein I do not attempt to read: I am willing to have a maximum of “relativity”; but I wonder if they have ever considered that if “relative” systems have no connexion and no common object, each is absolute; and if they have a common object, or form a connected group of perspectives, then they are only relative views, like optical illusions, and the universe is not ambiguous in its true form.

When I was ill with the grippe (which is what I am supposed to have had) the doctor, I think, gave me some “dope” or other: any how my imagination was very active and I scribbled in pencil four chapters of my novel, including the end: but I have not dared to reread them, for fear they may be pure nonsense.

People never believe in volcanoes until the lava actually overtakes them.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Three, 1921-1927. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.