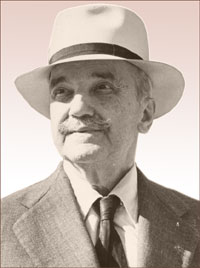

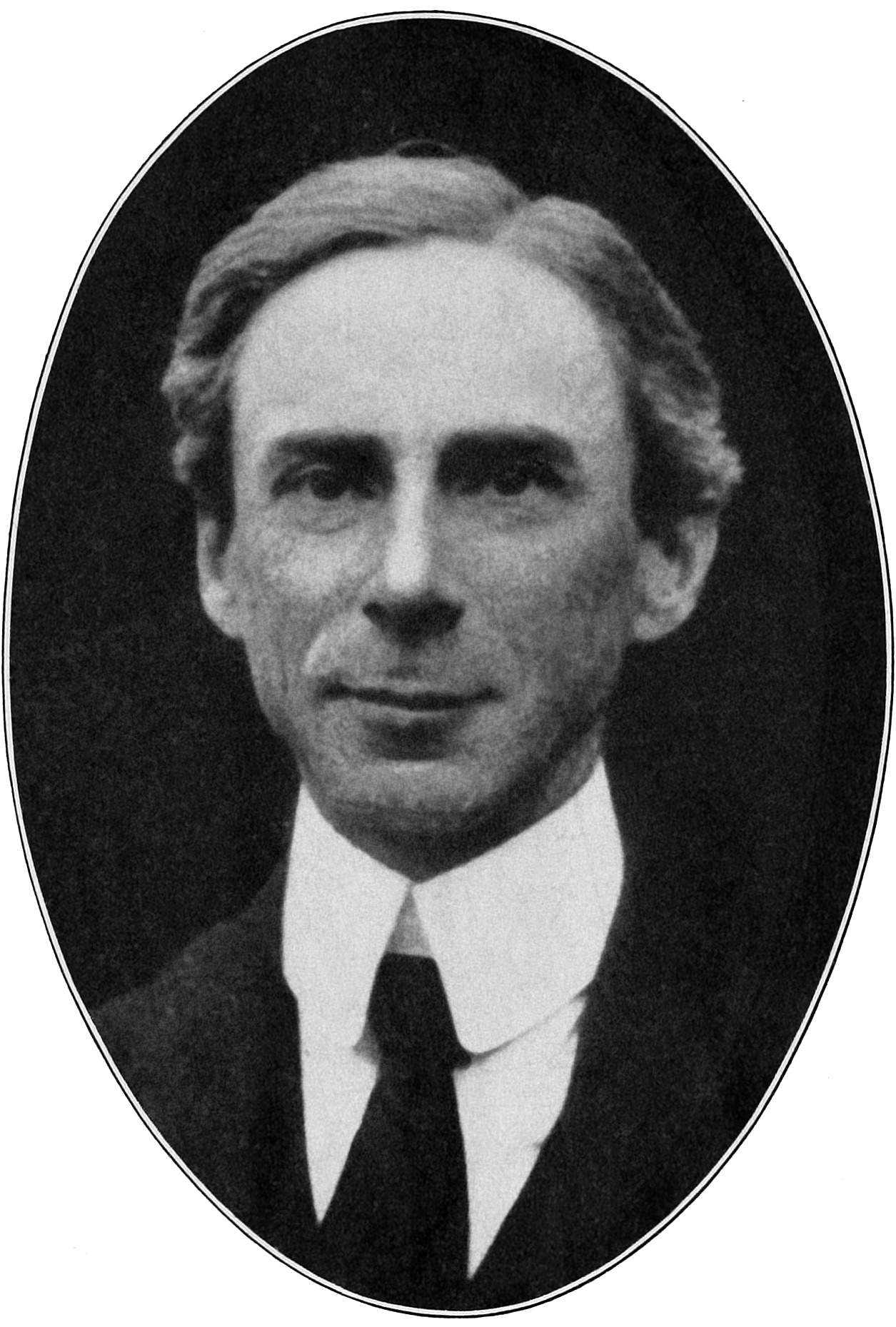

To Susan Sturgis de Sastre

To Susan Sturgis de Sastre

Cambridge, England. March 28, 1915

Of course, reading the papers and thinking about the war takes up a large part of one’s time and energy. Until it is over I can’t expect to resume my ordinary manner of life.

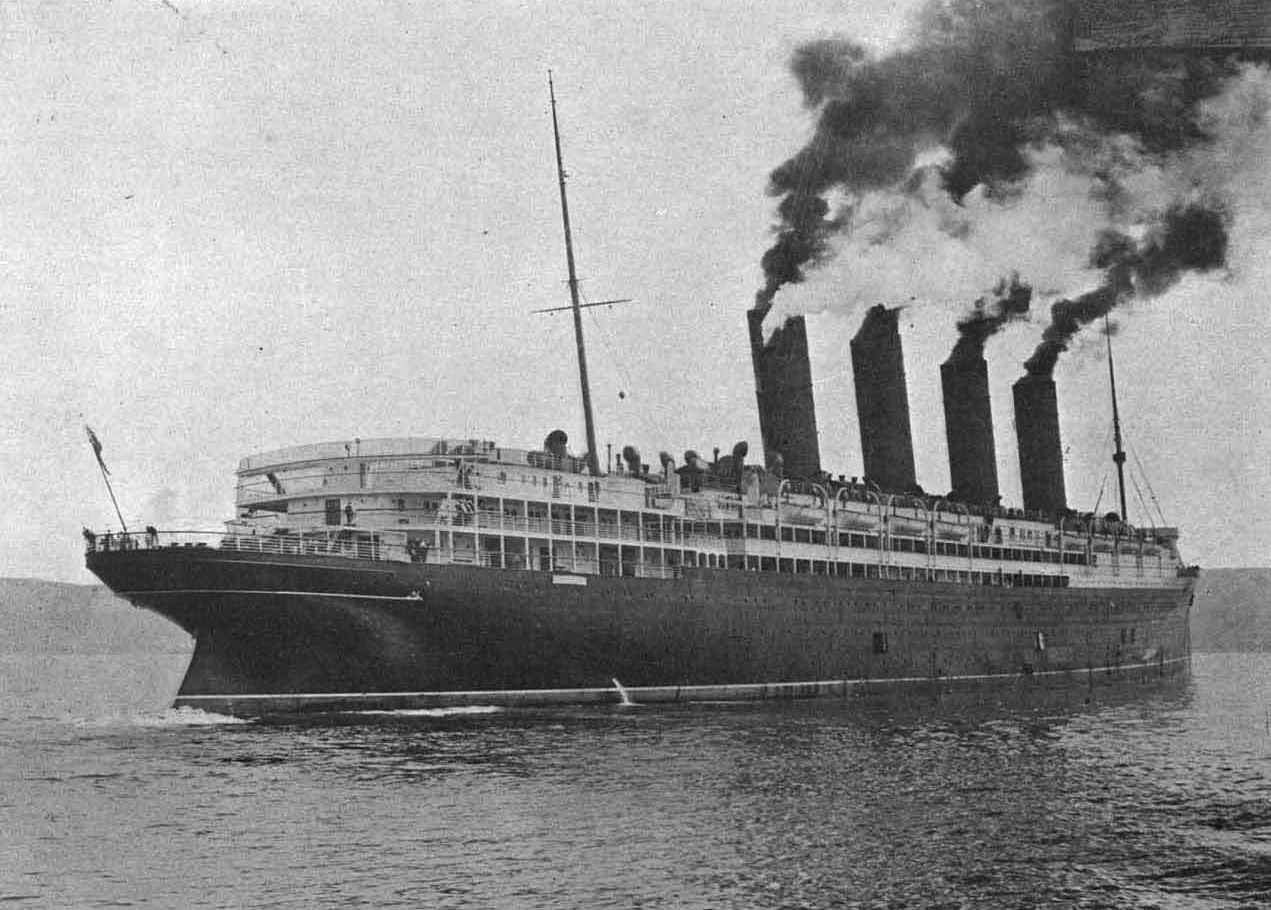

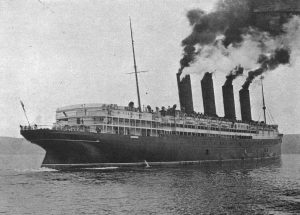

Something Josephine said in her letter made me suspect that she is thinking of America again for the autumn. Unless the war is over (which is hardly likely) we might have some difficulty in coming through France, and might be torpedoed (although so far no good liner has suffered, partly because they are too fast to be caught and partly because the Germans don’t want to exasperate the U.S. by giving the tourists a salt bath)

I went to dinner with the Carlino Perkins’s the other night—my first dinner-party for years—and didn’t like it at all. Old frowsy people with nothing but conventional chit-chat and thread-bare sentiments about the war. Bessie Ward herself is animated and doesn’t look very old, but she talks of one thing and thinks of another—a horrid trick—and is always changing the subject and being facetious, which also is a bit tiresome. However, I should have forgiven it all if they had had champagne, but they didn’t.

There is no doubt that the English climate and way of life suit me admirably. Perhaps, when I settle down, it will be here after all, although I no longer feel the same positive pleasure in being in England which I felt twenty years ago. The positive pleasure now is to be in the South—Rome, Seville, the Riviera, the bay of Naples. But England makes a good “home.”

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Two, 1910–1920. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: Alderman Library, University of Virginia at Charlottesville.

To John Hall Wheelock

To John Hall Wheelock