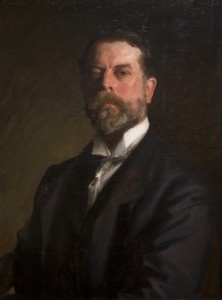

To Horace Meyer Kallen

To Horace Meyer Kallen

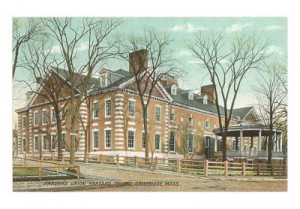

Cambridge, Massachusetts. February 5, 1908

I don’t know what the general effect of Moore’s system is: how does he attach existence to Being? But I like the clearness with which he holds to the intent of thought and avoids those psychological sophisms to which we all, brought up under the blight of idealism, remain so prone. For that lesson I am willing to forgive him all his narrowness and general incapacity. I have no doubt he is a most disagreeable and unfair person. But he is one from whom we can learn something, which is more than can be said of most contemporary writers. Russell is far better known to me, both personally and as a writer, and I feel as if I agreed with him pretty thoroughly, inspite of all differences in temperament and in knowledge. At least, disagreements with Russell don’t trouble me, because I feel them to be due to additional insights, now on his part now on mine: while disagreements with a haphazard person like James are more annoying, because they come from focussing things differently, from being schief. You may be quite right in thinking that I agree almost entirely with what James means: but I often hate what he says. If he gave up subjectivism, indeterminism, and ghosts there would be little in “pragmatism”, as it would then stand, that I could object to. Of course, pragmatism in a wider sense involves an ethical system, because we can’t determine what is useful or satisfactory without, to some extent, articulating our ideals. That is something which James doesn’t include in philosophy. Dewey is far better in that respect, and I notice he even begins to talk about the ideal object and the intent of ideas! What a change from those “Logical Studies” in which there is nothing but social physiology!

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book One, [1868]-1909. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: American Jewish Archives, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati OH