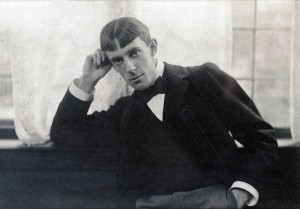

To Robert Traill Spence Lowell Jr.

To Robert Traill Spence Lowell Jr.

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. January 26, 1949

If when already a man of experience and an accomplished poet you come to Europe for the first time and land in England, your sense for that country will be that it is odd, small, somewhat annoying in being different from the United States; and it will take time, which perhaps you will not care to spend there, for you to feel its charm If on the contrary you sail into the Strait of Gibraltar (and your steamer will probably touch there, so that you could “take in” the Rock, the port, and the Spanish coast, as well as the spurs of the Atlas on the African shore) you would receive an impression of grandeur with details in the foreground of an original simple ancient truly human civilization. This would be increased, if you stopped at Gibraltar, in order to go from there to Tangiers and perhaps inland into Morocco. I don’t know how profoundly things may have changed since I was at Tangiers in 1893; but then Tangiers was barbaric beyond words, the Moors thoroughly Moorish, camels, donkeys, and sheep resting on the bare ground of the vast market amid pools of urine, and on a rock that emerged in one corner, a minstrel, looking like Homer, reciting at intervals to a sparse audience, all sitting on the ground. He was repeating, I was told, old tales of chivalry, like The Romance of the Cid. I won’t say more: but everything was as remote non-Christian, savage, and yet tightly established and dignified as the Old Testament. If instead of going to Morocco you made a short trip into Spain, the scene say in Ronda, Cadiz, and Seville, would be less antique but just as incomparable with anything in America as Africa itself. You might not like what you saw, but you would not think it, like England, an irrational variant of things at home, and annoying. Even if you came straight to Genoa or Naples your first impression would be of the Mediterranean, blue and tideless, with streets and houses down to the water’s edge, and the manners and colours of a beautiful world. As you went on to Rome, Florence, Milan and Venice your comfort would increase with your appreciation of the glories of art and nature, and nowadays you would hardly feel that you were socially among barbarians. At certain moments, in certain places, you would feel the opposite. If then from Italy made your way to Switzerland, Paris, and perhaps Flanders, you might be fascinated by the order and justness of things, and their pleasing quality, like well-cooked food and refinements of art and manners. If from this then you finally reached England, you would cry at Dover: Almost like home! England then would have to make no apologies for not being American enough, and might seem, especially if you went into the country, the most perfectly home-like of places, more than anything since ancient Greece on the human scale clement, quiet, and friendly. By all means come if you can by the Pillars of Hercules, let Europe sink into you in chronological order, without comparisons with America, as it grew and as it was gradually overpowered by modernity.

I don’t understand what Eliot’s selection of your poems is for, if he doesn’t tell us why he has made it and is not thereby going to introduce you to the British as well as to the genteel American public: which I supposed involved a vast sale. I am sorry if I was wrong. I have perhaps not studied Eliot’s poetry or criticism as thoroughly as they deserve. I have not even seen his “Family Quarrel” which I only learned the other day, by chance, was a pendant to Oedipus. I agree with you in admiring his sensibility. He has caught that from the French critics who almost by heredity seem to voir juste. But I think he is timid, mincing, too content with non-radical views. All views should be radical, but not absolute; an opposite radical insight should redress the balance. But he is refined and safe in his indecision. Eliot was once in one of my classes, and perhaps it was I that gave him his first start in Dante; but he has gone far beyond me in studying him and using him. It is his approach to Catholicism, which I didn’t need. Perhaps because his Catholicism was so blameless and purified, he decided to sing on that perch. You and I know better, don’t we? the entrails of that angel.

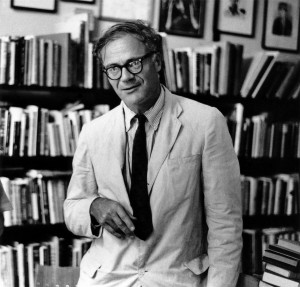

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA