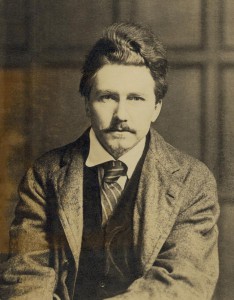

To Martin Birnbaum

To Martin Birnbaum

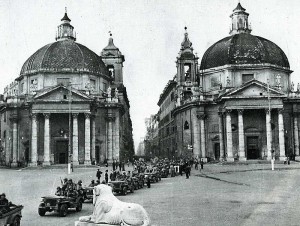

Via Santo Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. January 22, 1947

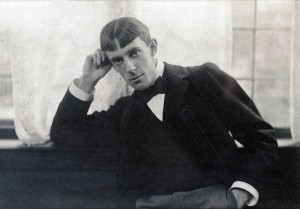

But there is a semi-philosophical point that kept coming into my head as I read what you say about Aubrey Beardsley and also about Behmer (whom I had never heard of!). You seem to be troubled about the impropriety actual and suggested of their compositions. Now I see that it would be shocking to exhibit an obscene drawing in Church or in a lady’s drawingroom; but I do not see anything painful in an obscene drawing because it is obscene; if it is seen at a suitable time and place, and is not a bad composition in itself. Now I think in Aubrey Beardsley there often is bad taste, like bad taste in the mouth, because his lascivious figures are ugly and socially corrupt. The obscene should be merry and hilarious, as it is in Petronius: it belongs to comedy, not to sour or revolutionary morals. It is the mixture of corrupt sneers and hypocrisy with vice that is unpleasant to see, unless it is itself the subject of satire, as for instance in old English caricatures.

But in Beardsley the charm of the design and the elegance of the costumes and of the ballet character of all the movement seem to recommend the vice represented: and that is immoral. But licentiousness is natural in its place, and the fun of impropriety is also not vicious; and I don’t see why the books or pictures illustrating these things should be regrettable. The Arabian Nights, in Mardrus, seem to me purely delightful. Robert Bridges, who was a good friend of mine, used to deplore the sensuality in Shakespeare, and say he was the greatest of poets and dramatists, but not an artist. I think that some of the jokes in Shakespeare are out of place; for instance what Hamlet says to Ophelia in the play scene; but in a frank comedy, the same and much broader things would be excellent, as in Aristophanes: and the public would soon select itself that patronized such shows. But I am afraid I am a hopeless pagan. Aubrey Beardsley, converted to Catholicism, might beg to have his naughty drawings destroyed, and perhaps they were not all in themselves beautiful or comic: but I should not destroy anything aesthetically good. The beautiful is a part of the moral; and the truly moral is a part of the beautiful: only they must not be mixed wrong, any more than sweets and savouries.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Seven, 1941-1947. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006.

Location of manuscript: Unknown