To Manuel Komroff

To Manuel Komroff

C/o Brown Shipley & Co

123 Pall Mall, London

Rome. January 12, 1928

Dear Mr Komroff,

It is very kind of you to send me your new book. It introduces me to a kind of world rather different from the one I live in. If vice in the Eighteenth century lost half its evil by losing all its grossness, in recovering now-a-days all its grossness it seems to have lost the other half: it has ceased to be evil at all, in the old moral sense, and has become simply an unpleasant fatality. I am not quite sure that I understand your philosophy; but I suppose you wouldn’t suggest that apart from the love of life or the Juggler’s Kiss, existence would be satisfactory. If your hero had stayed at home and had married the girl he had been “petting” so assiduously, would that have been better in the end?

But I daresay this is beside the point. Art is not moral philosophy, you will say: and yet it is as poignant reality, not as art, that your book, and most recent books, can arrest attention. They are a horrid picture of fate.

Yours sincerely,

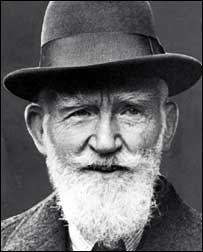

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Four, 1928–1932. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: Butler Library, Columbia University, New York NY