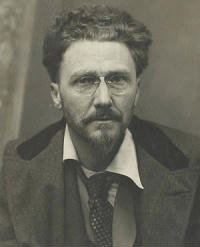

To Robert Seymour Bridges

To Robert Seymour Bridges

Hotel Bristol

Rome. January 8, 1925

Through the more and more frankly confessed mythical character of exact science, I . . . have been recognizing of late that the church is a normal habitation for the mind, as impertinent free thought never is. But there remains the old misunderstanding, the forcing of literature into dogma, and the intolerable intolerance of other symbols, where symbols are all. Here in Rome, in the Pincio and the Villa Borghese, I often watch with amazement the troops of theological students of all nations, so vigorous and modern in their persons, and I ask myself whether these young men can truly understand and accept the antique religion which they profess—especially the Americans (very numerous) with their defiant vulgar airs and horrible aggressive twang. Could the monks of Iona and the Venerable Bede have been like this? Was it perhaps after some ages of chastening that the barbarians could really become Christian and could produce a Saint Francis?

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Three, 1921-1927. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2002.

Location of manuscript: The Bodleian Library, Oxford University, England