To Daniel MacGhie Cory

To Daniel MacGhie Cory

Rome. January 5, 1939

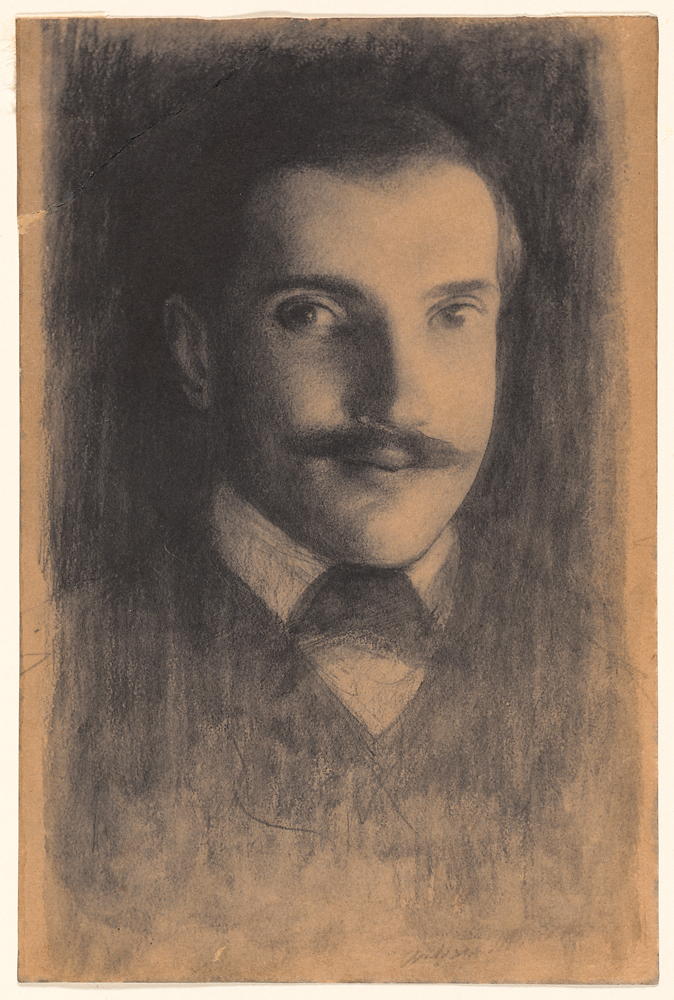

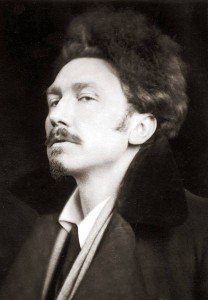

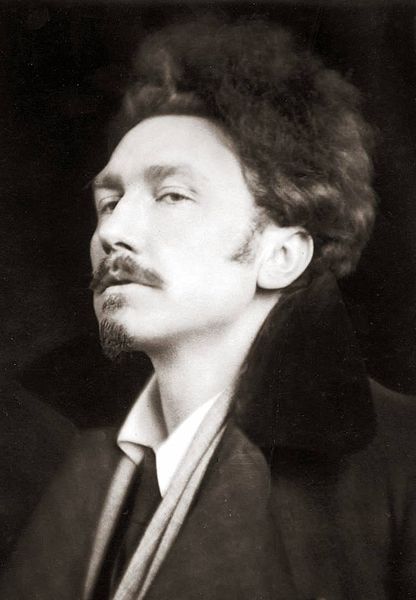

Yesterday evening I had a visit from—Ezra Pound!

He is taller, younger, better-looking than I expected. Reminded me of several old friends (young, when I knew them) who were spasmodic rebels, but decent by tradition, emulators of Thoreau, full of scraps of culture but lost, lost, lost in the intellectual world. He talked rather little (my fault, and that of my deaf ear, that makes me not like listening when I am not sure what has been said), and he made no breaks, such as he indulges in in print. Was he afraid of me? How odd! Such a dare-devil as he poses as! I had just been reading his article, and the one about him, in the Criterion, so that I felt no chasm between us—“us” being my sensation of myself and my idea of him . . .

His beard is like a painter’s and his head of hair (is it a wig?) like a musician’s. On the whole, we got on very well, but nothing was said except commonplaces.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Six, 1937-1940. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2004.

Location of manuscript: Butler Library, Columbia University, New York NY.

To Elizabeth Stephens Fish Potter

To Elizabeth Stephens Fish Potter