To Bruno Lind (Robert C. Hahnel)

To Bruno Lind (Robert C. Hahnel)

Via S. Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. January 10, 1952

Dear Lind

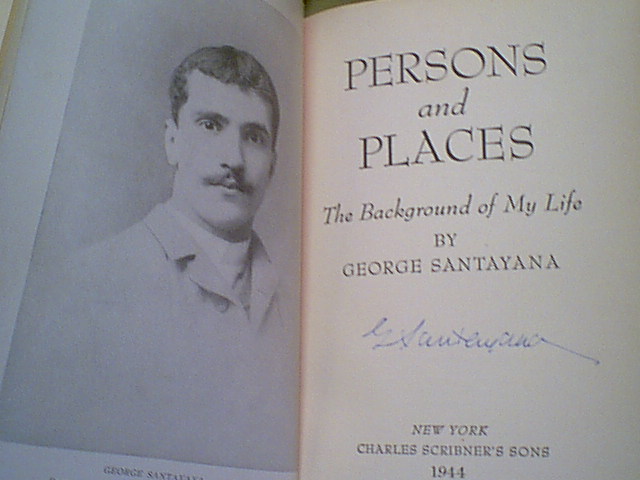

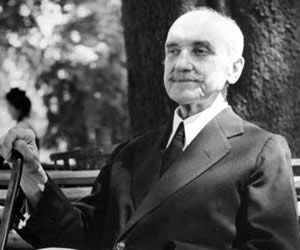

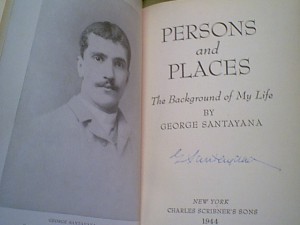

The enclosed letter has just arrived, and makes me wonder at the complexity of life now in the U.S. It was much simpler in my early days. It occurred to me at once when you first wrote, including a typed letter for me to sign, to the Photographic Department in the Library of Congress, how easily I could have sent you a copy of that sonnet–only 14 lines!–which I have a copy of, and besides know by heart. It is not a good sonnet considered as a work of classic poetic art, but it has many tentacles stretching into feelings, backward from 1895, when it was written, and foreward also. For you will notice that the line “Why mourn for Jesus?–Christ remains to us” accurately prophesies my “Idea of Christ in the Gospels” published more than fifty years later. 1895 had been the year of my first visit to Italy, in company with my friend Loeser, and it was on my return from there that I stopped at Arles, and other places in Southeastern France, before returning to America in a cattle-boat, for economy, from London to N.Y. in 16 days, without a touch of seasickness. I am not sure whether I speak of this voyage in any detail, or of the journey to Florence, Rome, Venice, and Milan, but they were all sentimentally important episodes for me at that time, when I was beginning to live my second, or rather my third life after my “Change of Heart” in 1893, described in the first chapter of the third book of “Persons & Places.” This was a reversion to solitude enriched by a great many absorbing scenes in the past and absorbing themes in the present and for the future. The sonnet in question has not been printed expressly because I think it would not be understood as yet; but it will appear in my “Posthumous Poems,” which Cory will publish; and it occurs to me to say all this to you now, since you happen to have searched it out at the Congressional Library, to which I sent it (when asked for something) together with the portrait by Andreas Andersen, made one year later, when my College Life at the Harvard Yard was coming to an end. The next year 1896–7 I was at King’s College; and when I returned to Harvard I lived in rooms in the town, like any outsider. All these things and others are pertinent, beginning with the Platonic Sonnets, to the various implications of that Sonnet at Arles. I give you these hints, knowing that you are penetrating, and wishing that your penetration may go right. When do you expect to have your book done, soon or years hence? I should like to be able to read it before it is published.

Yours sincerely G Santayana

P.S. Feb. 25, ’52

I had just sent off my letter about your sonnets on the Via Crucis, when this was returned to me–my second blunder in addressing letters to you. I send it again, hoping that this time it will reach you, as by chance it touches the same points as my last.

G.S.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: The Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.