To Mary Potter Bush

To Mary Potter Bush

Hotel Bristol, Rome

Rome. December 16, 1932

Dear Mrs. Bush

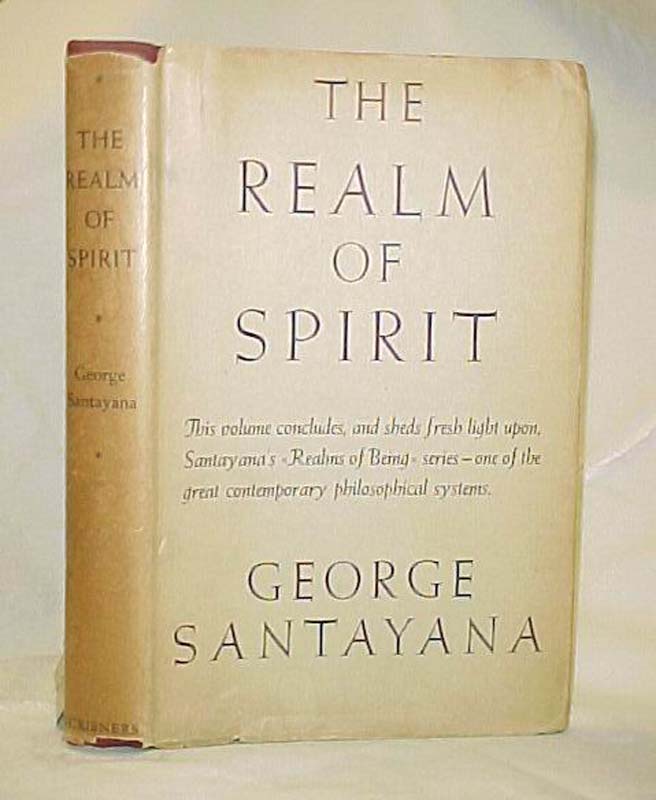

Thank you very much for your good Christmas wishes, which I reciprocate, and also for your address, which has enabled me to send off this morning three books of yours which I ought to have returned long ago. The Couchoud has made a great impression on me, and I have sent for others of the same series, to see what backing his views may really seem to have. I believe he is right in his religious psychology, that Christianity is an eschatological prophecy, not a personal morality corrupted into a theological system; but I am doubtful about the historical mixture of tradition, legend, & myth. Were it not that today being my 69th . . . birthday, I have made a good resolution to write no more articles and give no more lectures, at least until all my projected work is done, I might be tempted to write something on Couchoud & Co.: but I must abstain.

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Four, 1928-1932. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: Butler Library, Columbia University, New York NY.