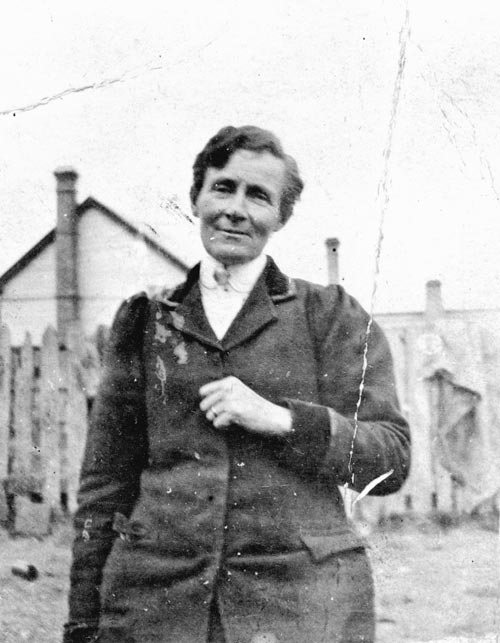

To Amy Maud Bodkin

To Amy Maud Bodkin

C/o Brown Shipley & Co.

123, Pall Mall, London, S.W.1.

Rome. November 22, 1934

Dear Madam,

It was very kind of you to send me your book, and you would be surprised if you knew the feeling of strangeness, as if I had forgotten my way about, with which I have read it. Not that you are not perfectly lucid, everywhere delicately perceptive and sympathetic, yet wonderfully sober, in your judgements. But you move in an enchanted world which I am afraid I never inhabited, even when I was young and felt more at home in poetry than I do now. You make me feel afresh that I was never a poet; or rather, to speak with entire frankness, that my sense for poetry has always been immersed in rhetoric, playing on the surface with rhyme, rhythm, assonance, and expressible sentiment, but grossly unaware of these haunting images and profound “experiences” of which you speak. So much so, that even after reading your book with extreme attention and a desire to understand, I am not yet sure what these archetypal patterns are: I mean, what they are ontologically. Everything in my old-fashioned mind seems to be covered by what was called “human nature” and “the passions”. We are all much alike in our capacities for feeling, as in our bodily structure. The doctors find, almost always, every organic detail in each of us exactly in its allotted place; and so the various sensuous phenomena that strike the imagination are bathed in each of us in exactly similar emotions. Do you think that these phenomena owe their power to the fact that they have occurred before in the experience of our ancestors? Do they operate telepathetically from one instance to another? I suspect that our historical knowledge now-a-days sophisticates our passions. When I hear the words: fidelium animæ per Dei misericordiam requiescant in pace, the magic of the chant lies no doubt in the universal (occasional) longing of mortal creatures to return to their mothers’ bosom or to that of Abraham but I may cloud or complicate that human emotion with a touch of the pathos of distance, at the thought that the same plaintive cry may have reechoed long ago in the catacombs. But this effect seems to me adventitious and unnecessary.

I mention these doubts only as a proof of the intense interest with which I have followed your analysis.

Yours sincerely,

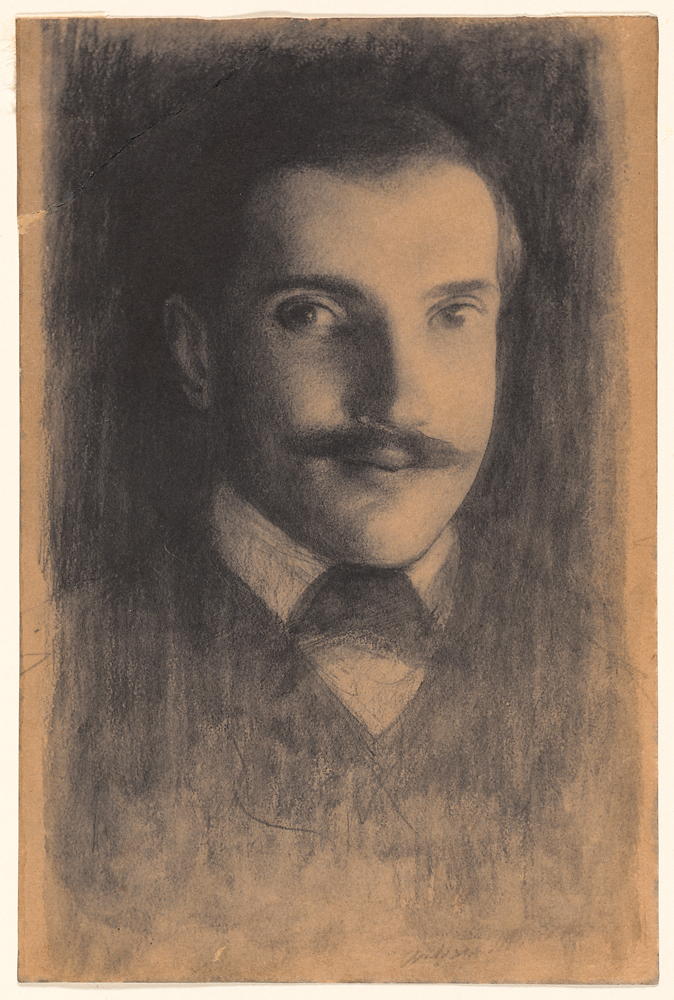

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Five, 1933-1936. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: The Bodleian Library, Oxford University, England.

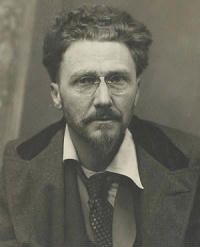

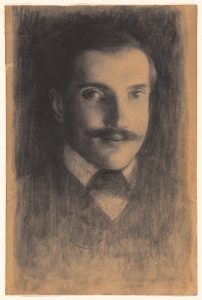

To Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson

To Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson