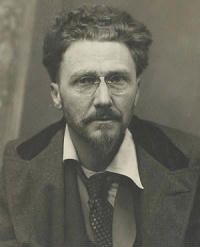

To Horace Meyer Kallen

To Horace Meyer Kallen

Hotel Bristol,

Rome. November 20, 1931

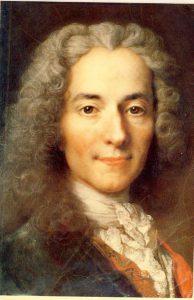

During two sunny afternoons on the Pincio I have absorbed your counterblast to religion. As a popular tract it is capital, beating the eloquent parsons at their own game. But isn’t it a bit discouraging that the work of Voltaire, which he did so thoroughly, should need to be done all over again after two hundred years? Is reason in the same parlous position as faith that it has to be dinned into the ears of each generation, or it will die out?

From my own point of view, if you were here, I should have some observations to make upon your presuppositions. You seem to regard “Religion” as merely myth and magic, that is, bad science: and of course you have a clear case in proving that bad science is worse than good science.

But is religion merely bad—hasty, poetical, superstitious—science? I should say religions (because each religion seems rather irreligious to the others) often had at least two important ingredients besides magic and myth. They were the intellectual and ritual expression of a particular ethos, nationality, or civilization; and they were also forms of “spiritual life”. Now I like very much what you say about science, if it became a religion, losing all its scientific virtue. A philosophy more or less inspired by science, like Epicureanism or Stoicism, may be a religion, or a substitute for religion: it may sanction a particular morality, and it may be refined into a form of spiritual life—I mean, into a great life-long dialogue between God and the soul of man. But science, as you conceive science—á la Dewey—is only experiment and invention; it is not a philosophy: and if any speculative ideas more or less illegitimately associated with it were set up as eternal truths, science would cease to be science to become bigotry. One of the happy, if somewhat disconcerting, discoveries of our—or my—later years has been precisely this: that science is intellectually blind and dumb, and that you may be a leading scientific expert without knowing what you think on any important question. It seems to me, therefore, that you ought not to pit “religion” and “science” so squarely against each other, as if they were rivals in the same field. A scientific philosophy might be a rival, or an ally, of certain religions or religious philosophies; but what chiefly attaches mankind to its religions is precisely the need of completing their traditional ethos, and their spontaneous spiritual life, with an appropriate speculative doctrine: and science is dumb on that subject and, in its scientific domain, ought to be dumb. Perhaps this explains in part why, in spite of you and Voltaire, religions still exist in the world

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Four, 1928-1932. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2003.

Location of manuscript: American Jewish Archives, Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Cincinnati OH.

To Dorothy Shakespear Pound

To Dorothy Shakespear Pound