To George Rauh

To George Rauh

Via S. Stefano Rotondo, 6

Rome. October 12, 1950

Dear Mr Rauh,

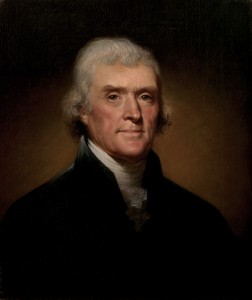

My chief divergence from American views lies in that I am not a dogmatist in morals or politics and do not think that the same form of government can be good for everybody; except in those matters where everybody is subject to the same influence and has identical interests, as in the discipline of a ship in danger, or of a town when there is a contagious disease. But where the interests of people are moral and imaginative they ought to be free to govern themselves, as a poet should be free to write his own verses, however trashy they may seem to the pundits of his native back yard. I think the universal authority ought to manage only economic, hygienic, and maritime affairs, in which the benefit of each is a benefit for all; but never the affairs of the heart in anybody. Now the Americans and OUN’s way of talking is doctrinaire, as if they were out to save souls and not to rationalize commerce. And the respect for majorities instead of for wisdom is out of place in any matter of ultimate importance. It is reasonable only for settling matters of procedure in a way that causes as little friction as possible: but it is not right essentially because it condemns an ideal to defeat because a majority of one does not understand its excellence. It cuts off all possibility of a liberal civilization. And it is contrary to what American principles have been in the past, except in a few fanatics like Jefferson who had been caught by the wind of the French Revolution. Americans at home are now liberal about religion and art: why not about the forms of government? I mean to send you or Lawrence Butler my new book on “Dominations and Powers”, when it appears, where all this is threshed out naturalistically. Glad to know that Lawrence is well. Yours sincerely

G Santayana

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Eight, 1948-1952. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008.

Location of manuscript: Unknown