To Robert Seymour Bridges

To Robert Seymour Bridges

9 Av. de l’Observatoire,

Paris. September 18, 1919

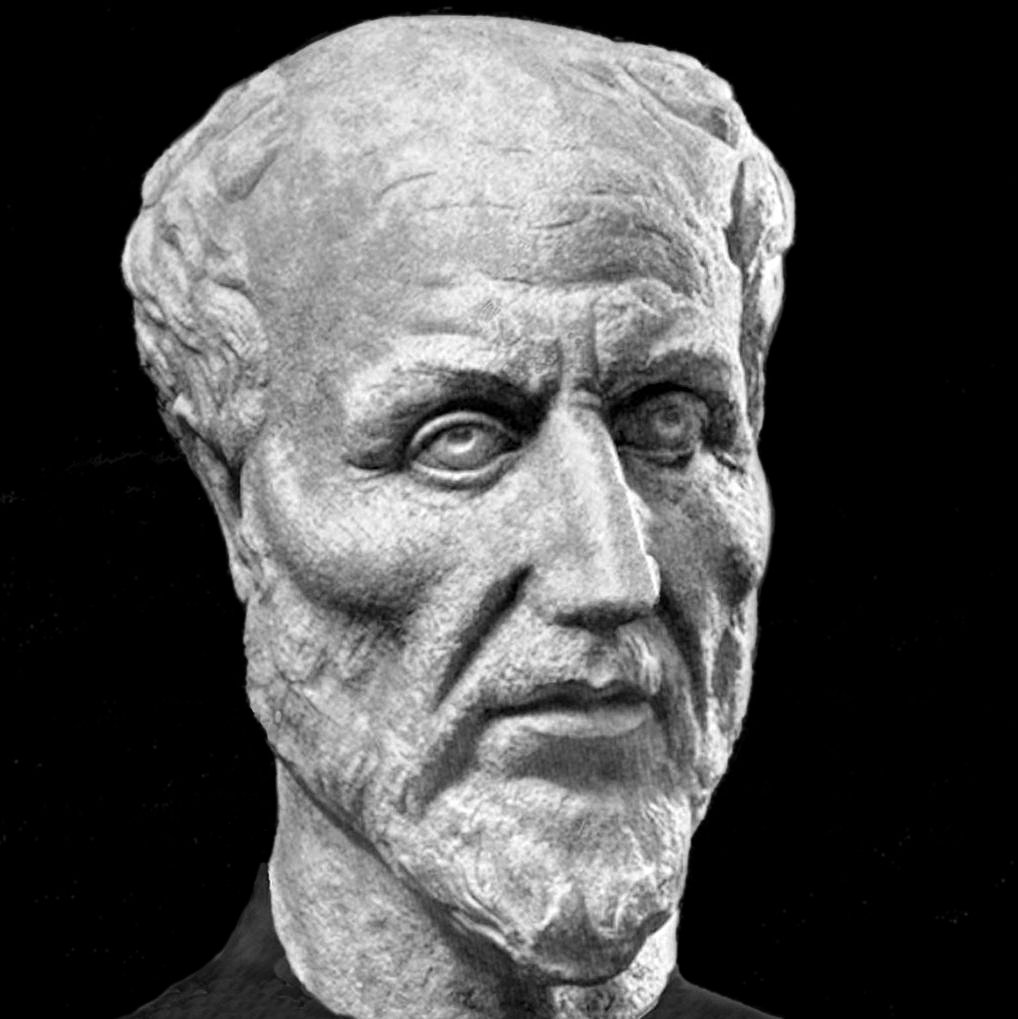

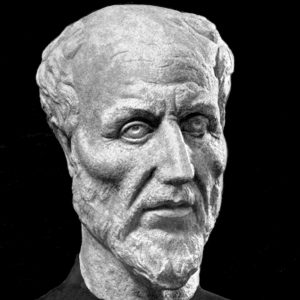

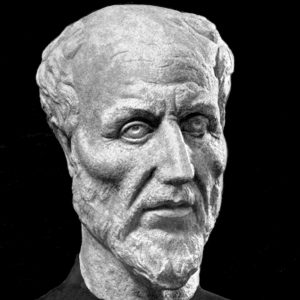

I won’t attempt to answer your letter seriatim, although each of the things you tell me prompts me to say something, but I can’t let Plotinus lie under the imputation you throw on him of not being a “good philosopher”. If you mean that his system of the universe is not a map of it, is not scientifically correct or in scale, of course I agree. But it seems to me a very great system, very “good philosophy”, and I am glad that the mystics in Oxford are taking him up, rather than pretending to find comfort in Hegel or in the meretricious psychology of Bergson. The doctrines of Plotinus are flights in the same direction as the doctrines of Christianity: they are not hypotheses intended to explain facts, but expressions invented for sentiment and aspiration. The world, he feels, is full of the suggestion of beauty and goodness, but of the suggestion only. In fact, it betrays and obliterates everything it tries to express, like an inscription in invisible ink that should become luminous only for a moment. And his question is: What does the world say, what does life mean, what is there beyond, . . . that might lend significance and a worthy origin and end to this wonderful apparition and to our passionate love and passionate dissatisfaction in its presence?

His system is an elaborate answer to this question. It is not a hypothesis but an intuition, and such rightness as it has is merely fidelity and fineness in rendering moral experience. Of course all those things he describes do not exist; of course he is not describing this world, he is describing the other world, that is, deciphering the good, just beyond it or above it, which each actual thing suggests. Even this rendering of moral aspiration is arbitrary, because nature really does not aspire to anything, and each living thing aspires to something different, in divergent ways. But this arbitrary aspiration, which Plotinus reads into the world, sincerely expresses his own aspiration and that of his age. That is why I say he is decidedly a “good philosopher”. It is the Byzantine architecture of the mind, just as good or better than the Gothic. It seems to me better than Christian theology in this respect, that it isn’t mixed up with history, it isn’t half Jewish, half worldly. It is the Greek side of Christian theology isolated and made pure; and that is the side of it which seems to me truly spiritual, truly sacrificial and penitentially joyful. That it is terribly superstitious and turns all physics into magic is an integral part of its poetic and expressive virtue. Every passion, every force, must be a devil or an angel, because it is agreed to begin with we are looking for the spirit in things.

I didn’t mean to go on in this way, especially as really I know Plotinus very little; but I feel a great power in him, a sublime illusion, as if some plant or some pensive animal had laboriously spun the moral dialectic of its own experience round itself, and called it the universe.

. . . Do you ever see the Athenaeum? I have kept on writing for it, although to be quite frank I don’t like the review as a whole, and don’t read it; but there is no other that I know of that would publish my effusions, and it is a great relief to have them in print. What is once out is done for, and one doesn’t have to think of it any more.

Are you going to America? If your society for the purification of the language is going to cleanse those Augean stables, I don’t envy it its labours. Why shouldn’t the English language of a hundred years hence be as different from ours as ours is from Shakespeare’s? I know you say he pronounced as we do: but we don’t write like him. The Americans have a great love of language for its own sake, and will develop new effects, if not new beauties. As one of them used to say whenever anything was censured: Let them have their fun!

From The Letters of George Santayana: Book Two, 1910-1920. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001.

Location of manuscript: The Bodleian Library, Oxford University, England.

To Gilbert Seldes

To Gilbert Seldes